Today’s PAAD is about the surgical and medical treatment of pediatric seizures and status epilepticus. The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia’s Quality and Safety Committee, chaired by Drs. Priti Dalal and Anna Clebone, and its Checklist subcommittee, also chaired by Priti and Anna, continuously review, upgrade, and revise SPA’s printed pediatric emergency checklists AND its associated PediCrisis app. Over the past 2+ years, there has been great debate amongst the committee members about adding a status epilepticus treatment card. In way of full disclosure, I was vehemently opposed to this because as I learned as a visiting medical student at CHOP in 1976, general anesthetics are the ultimate treatment for status epilepticus. And we, after all, are anesthesiologists and not emergency medicine doctors so why not use the ”nuclear option” to stop convulsions rather than sling shots? How potent are the general anesthetics as anti-convulsants? As you will see in the discussion below, general anesthetics are the ultimate, final treatment in any treatment seizure algorithm. They will work when everything else fails. I learned this as a medical student. I was following the PICU (and anesthesiology) fellow, Dr. Charlie Cote who was called to the ER to help with a child in status epilepticus. Charlie arrived, took a look and asked “why is the child still seizing”? The ED attending explained that “the child had already received a dose of diazepam and a loading dose of phenobarbital. More anticonvulsants would likely cause apnea”. Charlie’s response which astounded me was “so what? I can handle that!”. He promptly gave the child a dose of thiopental, the seizure stopped, and Charlie managed the airway. All I could think of was “WOW”!

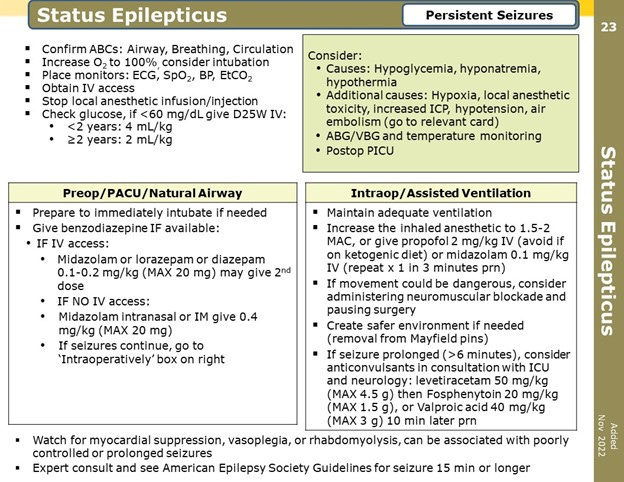

I lost the status checklist argument and a final version of the checklist was approved and is now available in a PDF format on the SPA website (see figure). The PediCrisis version will appear in the next upgrade.

https://pedsanesthesia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SPAPediCrisisChecklistsNov2020.pdf

I’ve invited 2 new reviewers, Drs. Justin Hamrick and Jennifer (“Jenny”) Hamrick of the Anesthesia Service Medical Group, Inc. (ASMG), San Diego to assist. Both Justin and Jenny are Board certified in Anesthesiology and Pediatrics (Justin is also Board certified in Pediatric Critical Care Medicine) and were my former fellows at Johns Hopkins. Myron Yaster MD

Original article

Amy Y Tsou, Sudha Kilaru Kessler, Mingche Wu, Nicholas S Abend, Shavonne L Massey, Jonathan R Treadwell. Surgical Treatments for Epilepsies in Children Aged 1-36 Months: A Systematic Review. Neurology. 2023 Jan 3;100(1):e1-e15. PMID: 36270898

Original article

Ekin Soydan, Yigithan Guzin, Sevgi Topal, Gulhan Atakul, Mustafa Colak, Pinar Seven, Ozlem Sarac Sanda, Gokhan Ceylan, Aycan Unalp, Hasan Agin. Clinical Features and Management of Status Epilepticus in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2023, 39, 142-147. PMID: 36790917

Original article

Kevin Gorsky, Sean Cuninghame, Jennifer Chen, Kesikan Jayaraj, Davinia Withington, Conall Francoeur, Marat Slessarev, Angela Jerath. Use of inhalational anaesthetic agents in paediatric and adult patients for status asthmaticus, status epilepticus and difficult sedation scenarios: a protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021 Nov 10;11(11):e051745. PMID: 34758996

Early life epilepsies (epilepsies in children 1–36 months old) are common and may be refractory to antiseizure medications. “Most patients are initially treated with antiseizure medications (ASMs); however, after a first or second ASM fails to control seizures, the likelihood of sustained seizure freedom with any ASM substantially declines. In such contexts, other treatments including dietary therapy, surgery, or electrical stimulation devices are considered. Compared with other treatments, surgical treatments are distinctive in aiming to address underlying structural causes of epilepsies but are likely underused. Resection or disconnection of epileptogenic brain tissue can lead to seizure freedom (curative surgery) or seizure reduction (palliative surgery). Several factors may affect the outcomes including underlying pathology, surgery type, location, extent of resection, and concordance of presurgical evaluations. These factors affect judgements regarding epileptogenic zone identification and decisions regarding resection boundaries that aim to optimize benefits for seizure management while minimizing potential functional deficits”.1 Tsou et al.1 conducted a systematic review commissioned by the American Epilepsy Society to assess evidence and identify evidence gaps for surgical treatments for epilepsy in children aged 1-36 months without infantile spasms. They found that “Although existing evidence remains sparse and low quality, some infants achieve seizure freedom after surgery and ≥50% achieve favorable outcomes. Future prospective studies in this age group are needed. In addition to seizure outcomes, studies should evaluate other important outcomes (developmental outcomes, quality of life [QOL], sleep, functional performance, and caregiver QOL)”.1

“Status epilepticus is defined as seizures lasting >5 minutes and 2 or more separate seizures in which consciousness is not fully recovered.2 Patients who do not respond to first-line and second-line treatments defined as refractory SE (RSE), and seizures lasting longer than 24 hours despite these treatments were defined as super-refractory SE (SRSE)”.2,3 Soydan et al.3 retrospectively reviewed the clinical characteristics of patients admitted to their single center PICU (Turkey) between January 2015-December 2019. As in the SPA checklist, first line therapy are the benzodiazepines. Second line therapies include sodium valproate, fosphenytoin, phenobarbital, and levetiracetam. If these therapies fail, induction of general anesthesia with or without endotracheal intubation is the final steps in the algorithm. General anesthesia consisted of continuous infusions of benzodiazepines (midazolam), barbiturates (thiopental), propofol, and/or ketamine. They didn’t use vapor anesthetics because it could not be delivered in their ICU. Finally, they underline the importance of continuous electroencephalographic monitoring because status epilepticus can commonly be occurring without overt clinical convulsions.

“Inhaled general anesthetics are often reserved in ICUs as therapies for refractory and life threatening status asthmaticus, status epilepticus, high and difficult sedation need scenarios”.4 The limitations to their use is the lack of familiarity by the PICU staff with volatile anesthetics, lack of trained personnel, equipment and scavenging, and cost. (Most PICU ventilators require 60 L/minute fresh gas flow which would exhaust your hospital’s sevoflurane supply in about a day or two and would cause Diane Gordon and Liz Hansen, our sustainability gurus to infarct!) In todays’ PAAD, the author’s present the limited data on the use of general anesthetics in status epilepticus. Their bottom line: Inhaled volatile agents are incredibly effective and provide their anticonvulsant effects by promoting central inhibitory GABA A pathways and lowering activity of excitatory NMDA pathways.

What are your thoughts? Does your institution have the ability to provide volatile general anesthetics in your PICUs? Are you called for assistance in treating status epilepticus? Have you had to deal with seizures in the PACU? Finally, how do you treat the continuation of anticonvulsants perioperatively? Please send your responses to Myron and we’ll post in the weekly, Friday Reader response.

References

1. Tsou AY, Kessler SK, Wu M, Abend NS, Massey SL, Treadwell JR. Surgical Treatments for Epilepsies in Children Aged 1-36 Months: A Systematic Review. Neurology. Jan 3 2023;100(1):e1-e15. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000201012

2. Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus--Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. Oct 2015;56(10):1515-23. doi:10.1111/epi.13121

3. Soydan E, Guzin Y, Topal S, et al. Clinical Features and Management of Status Epilepticus in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Pediatric emergency care. Mar 1 2023;39(3):142-147. doi:10.1097/pec.0000000000002915

4. Gorsky K, Cuninghame S, Chen J, et al. Use of inhalational anaesthetic agents in paediatric and adult patients for status asthmaticus, status epilepticus and difficult sedation scenarios: a protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open. Nov 10 2021;11(11):e051745. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051745