The iPACK Block in Kids: Underused, Understudied, Unfairly Ignored?

Michelle Carley, Deepa Kattail, Walid Alrayashi, Rita Agarwal, John G. Hagen

Original article

Sadacharam K, Mandler T, Staffa SJ, Pestieau SR, Fuller C, Ellington M, Sparks JW, Fernandez AM; SPAIN-ACL Investigators. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Outcomes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Surgery in Pediatric Patients: Society of Pediatric Anesthesia Improvement Network. Anesth Analg. 2025 Jan 29. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000007376. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39879136.

Although this article has been reviewed at least twice before in the PAAD (https://ronlitman.substack.com/p/acl-and-regional-nerve-blocks-to and https://ronlitman.substack.com/p/regional-anesthesia-and-pain-outcomes?utm_source=publication-search) it brought up a topic that caused a lot of questions and comments and led to us to do a more in depth review of the topic.

What is an iPack Block?

For years, sciatic blocks were the standard for posterior knee pain following surgery despite their drawback: sensory and motor block of not only the knee, but also the foot. Foot drop after ACL surgery wasn’t rare, and it wasn’t welcome. As the demand for motor sparing techniques grew—particularly in ambulatory procedures—the search for alternative techniques gained momentum.1

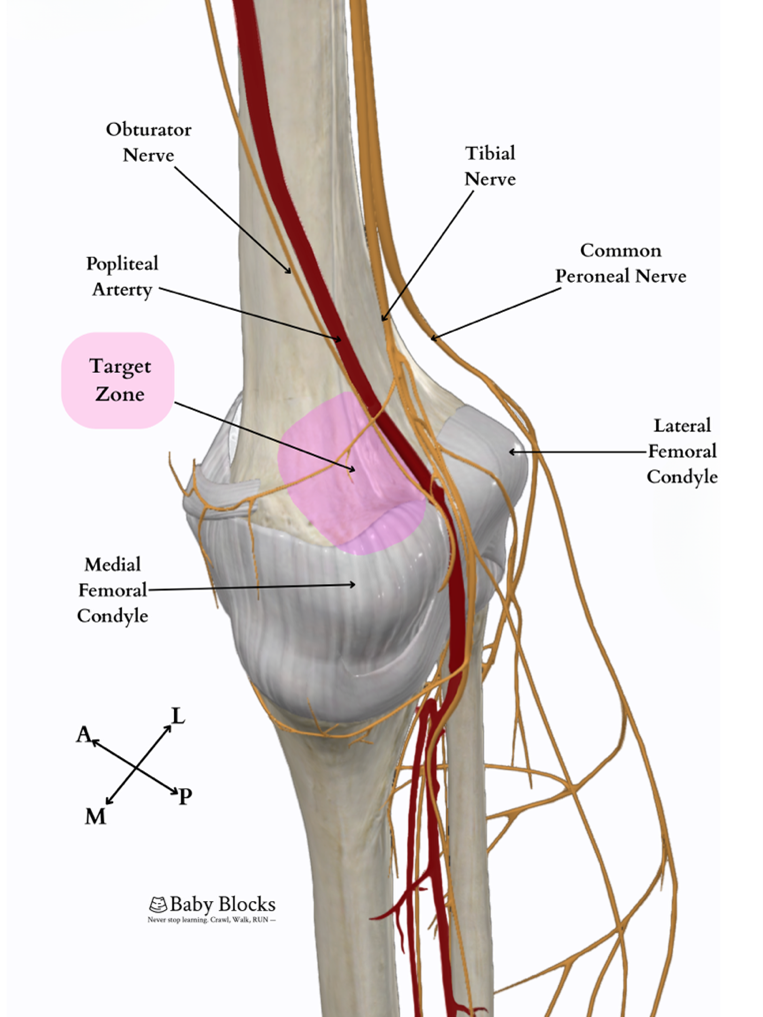

The iPACK block emerged as a promising solution. Short for infiltration between the popliteal artery and capsule of the knee, the iPACK block targets the terminal articular branches of the tibial, common peroneal, and obturator nerves, providing posterior knee analgesia while sparing motor function.2 It’s elegant, specific, and may be very useful in pediatric and adolescent patients.

So, let’s talk about what it is and how to do it.

Why Was the Posterior Knee So Hard to Get Right?

Femoral nerve blocks—and later, adductor canal blocks— provide analgesia for anterior knee coverage after ACL reconstruction. But posterior knee pain stubbornly persisted. Sciatic blocks offered reliable posterior coverage, but often at the cost of distal motor function. As the focus shifted toward motor-sparing techniques—especially in ambulatory sports procedures—patients and surgeons alike began to seek alternatives. The iPACK offered an alternative option. First described by Thobhani et al.2 in 2017, it was designed to target the genicular innervation of the posterior knee—without affecting distal motor function while providing analgesia to facilitate early mobilization.3 Cadaveric studies showed consistent spread to the relevant articular branches and middle genicular nerves, while reducing proximal tibial or common peroneal nerve blockade.4

So Why Isn’t Everyone Doing It in Kids?

Until recently, published pediatric cases were nearly nonexistent. The most recent PRAN publication5 doesn’t list the iPACK as a category, since its most recent publication in 2018 only includes data through 2015. More broadly, pediatric regional anesthesia has historically lagged behind adult practice. Many innovations, like the iPACK, originated in the adult realm and have been slower to infiltrate into pediatric practice for any number of reasons such as a lower relevant case volume, limited exposure, and a general unfamiliarity. As surgical teams increasingly aim to preserve motor function and promote early mobility, the iPACK offers a compelling motor-sparing alternative. While it doesn’t provide the same degree of posterior coverage as a sciatic block, it allows anesthesiologists to incorporate regional anesthesia into the care pathway—supporting recovery, reducing opioid use, and aligning with the evolving goals of pediatric surgical care.

At Hospital for Special Surgery (New York City), over 1,100 iPACK blocks have been performed in patients under 18 since 2021. The most common indications have been ACL reconstructions and MPFL repairs. Nearly all of these were paired with adductor canal blocks. More recently, regionalists have been adding genicular and anterior femoral cutaneous blocks to enhance motor-sparing analgesic coverage of the anterior knee.

Clinical pearls:

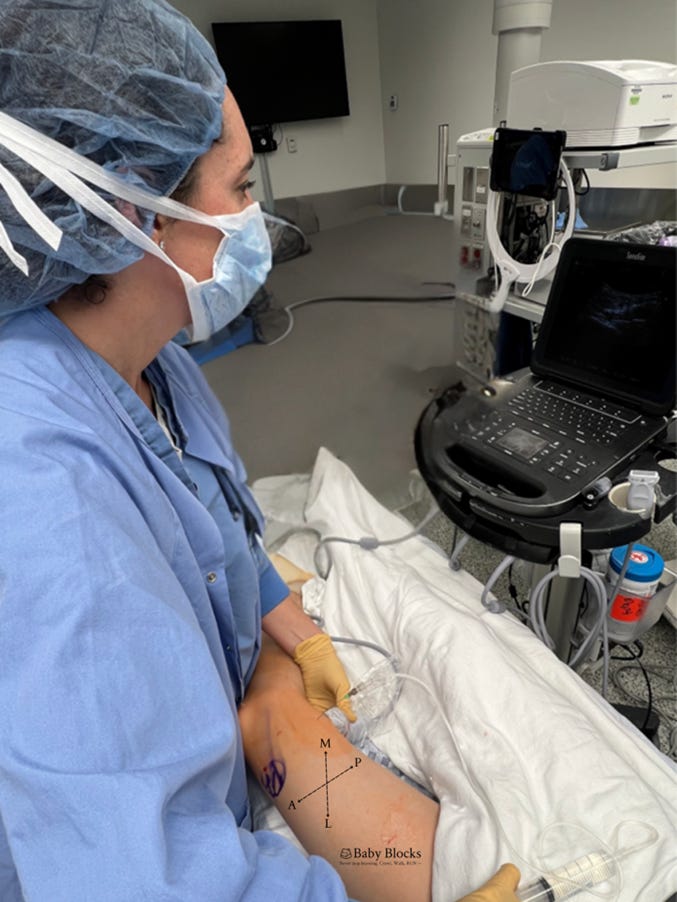

· Technique matters. Most of the blocks are done under general or neuraxial anesthesia with ultrasound guidance

· Mind the spread. Straying too lateral or allowing posterior spread can impact the tibial or common peroneal nerves and result in a temporary postoperative foot drop.

From Sparse Data to Daily Practice

The SPAIN-ACL trial6 currently represents the largest published cohort of pediatric patients receiving iPACK blocks with 71 patients. As the technique continues to gain ground, there’s a clear opportunity for future work to clarify dosing strategies, refine techniques and learn collaboratively across institutions.

Technique

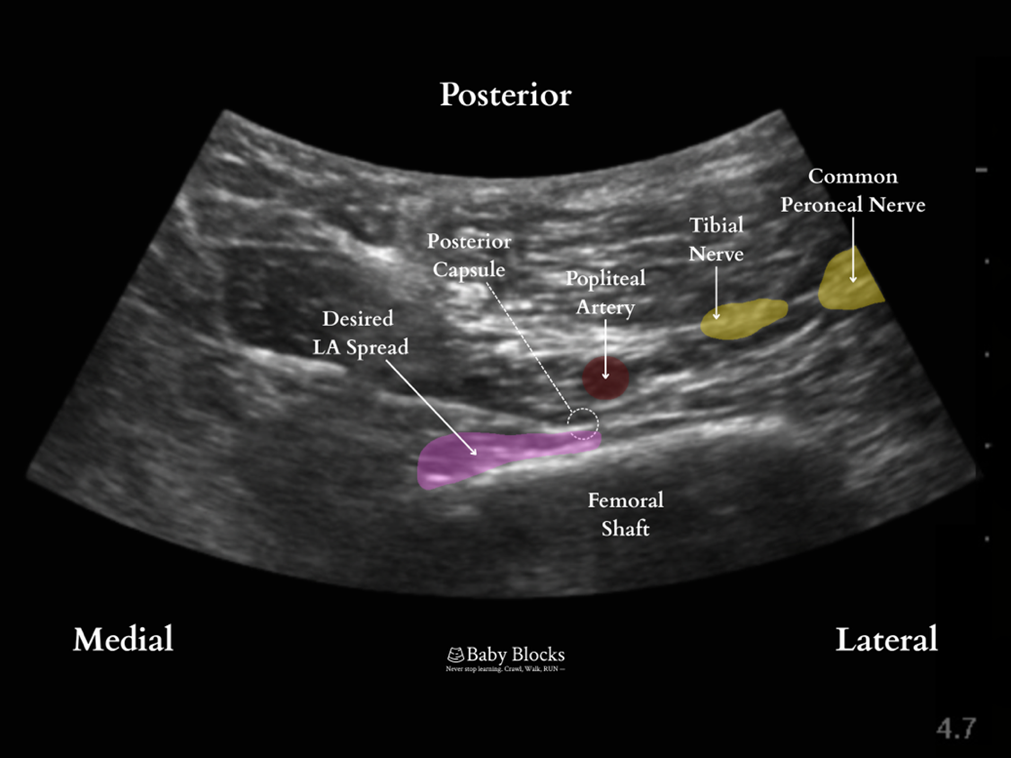

Interspace between the popliteal artery and the posterior capsule of the knee

The iPACK is essentially a field block of the terminal genicular branches of the posterior knee. Distal injection at the level of the femoral condyles results in more anterolateral spread while proximal injection at the level of the femoral shaft 1 cm, proximal to the base of the patella, results in more consistent spread anteromedially. Often used in conjunction with adductor canal block and genicular blocks to provide motor-sparing analgesia of the posteromedial knee joint.

Indications

Knee surgery, ACL surgery, MPFL, total knee arthroplasty.

Anatomy of the IPACK:

Relevant Anatomy: femoral condyles, femur, muscles, popliteal artery and vein

Lateral border: femur anterior to the popliteal artery

Anterior border: posterior aspect of the femur

Medial border: medial edge of the femur

Patient position

Supine with the leg bent or slightly frog-legged, linear or curvilinear probe from back of the knee

Equipment

· 4 inch, 22g block needle in a typical adolescent patient > 40 kg.

· Linear or curvilinear probe, linear probe preferred in patients <40 kg

Technique

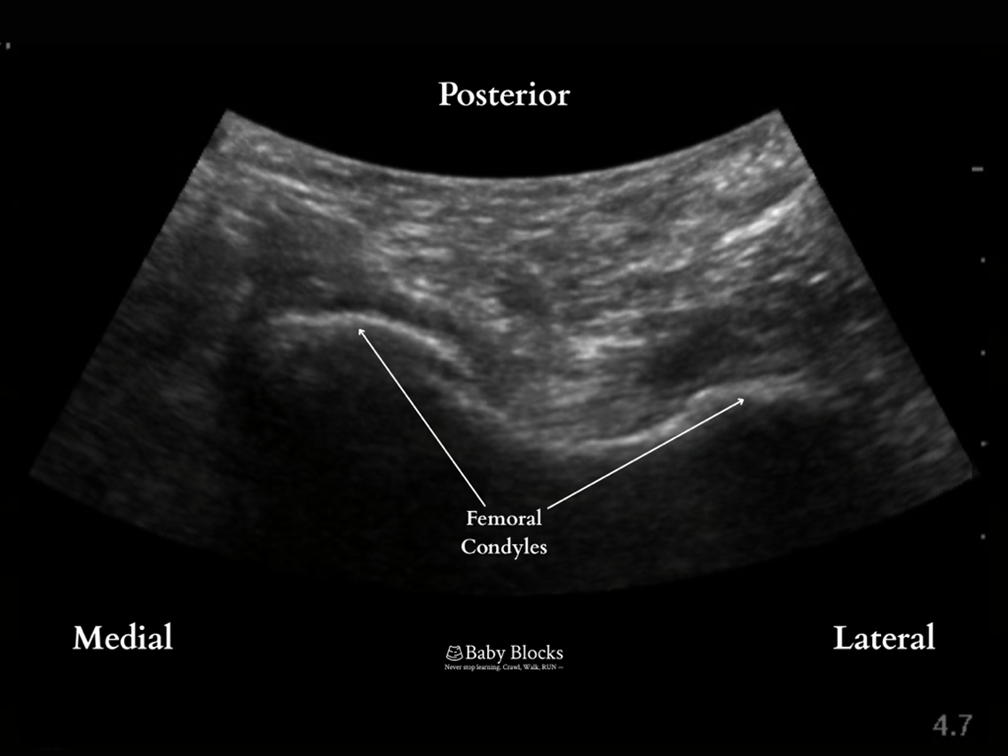

· Scanning is performed along the femur to find the posterior view of the femoral condyles.

· The probe is translated proximally until the condyles disappear from view and the femur is seen as a flat hyperechoic line.

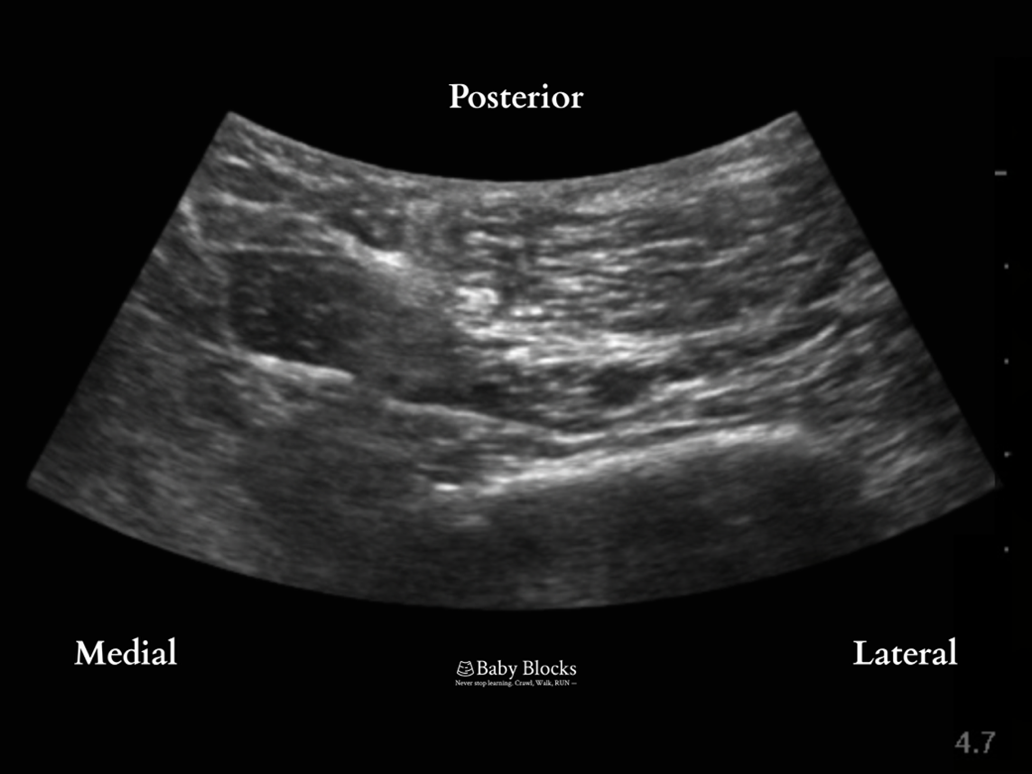

· The needle is advanced in-plane to make contact with the femur proximal to the knee joint on the medial aspect of the popliteal artery. Local anesthetic is deposited along the femur taking care not to deposit local anesthetic lateral to the popliteal artery to avoid sciatic nerve involvement and a foot drop.

Positioning

At the level of the femoral condyles

At the level of the femoral shaft. Popliteal artery is seen posterior to the femur, with the needle advancing from medial to lateral to make contact with the posterior femur just anterior to the artery.

Post-injection. Local anesthetic is infiltrated along the femur. Injection is made while withdrawing needle with spread visualized anteromedial to the artery

Dosing

Dose: 0.1-0.3ml/kg of 0.25% bupivacaine, depending on spread. Max 15-20ml.Coverage: posterior knee

Potential complications

· Bleeding

· Infection

· foot drop with lateral spread of anesthetic

· LAST

So what do you all think? Do you use it in your practice? Love it or leave it and why? Please send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post them on the Friday Readers’ Response.

PS from Myron: For those of you who wish to take an even deeper dive, Dr. Debnath Chatterjee, suggests the following:

https://www.baby-blocks.com/block-detail/ipack

References

1. Daoud AK, Mandler T, Gagliardi AG, et al. Combined Femoral-Sciatic Nerve Block is Superior to Continuous Femoral Nerve Block During Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in the Pediatric Population. Iowa Orthop J 2018;38:101–106. (In eng).

2. Thobhani S, Scalercio L, Elliott CE, et al. Novel Regional Techniques for Total Knee Arthroplasty Promote Reduced Hospital Length of Stay: An Analysis of 106 Patients. Ochsner J 2017;17(3):233–238. (In eng).

3. Teixeira F, Sousa CP, Martins Pereira AP, Gonçalves D, Sampaio JC, Sá M. Comparative Efficacy of iPACK vs Popliteal Sciatic Nerve Block for Pain Management Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Retrospective Analysis. Cureus 2024;16(1):e51557. (In eng). DOI: 10.7759/cureus.51557.

4. Tran J, Giron Arango L, Peng P, Sinha SK, Agur A, Chan V. Evaluation of the iPACK block injectate spread: a cadaveric study. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine 2019 (In eng). DOI: 10.1136/rapm-2018-100355.

5. Walker BJ, Long JB, Sathyamoorthy M, et al. Complications in Pediatric Regional Anesthesia: An Analysis of More than 100,000 Blocks from the Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network. Anesthesiology 2018;129(4):721–732. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/aln.0000000000002372.

6. Sadacharam K, Mandler T, Staffa SJ, et al. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Outcomes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Surgery in Pediatric Patients: Society of Pediatric Anesthesia Improvement Network. Anesthesia and analgesia 2025 (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000007376.