The Epidemic of Gender/Sexual Harassment in Anesthesiology: We Need Systematic Solutions

Bishr Haydar, MD and Odinakachukwu (Odi) Ehie, MD, FASA

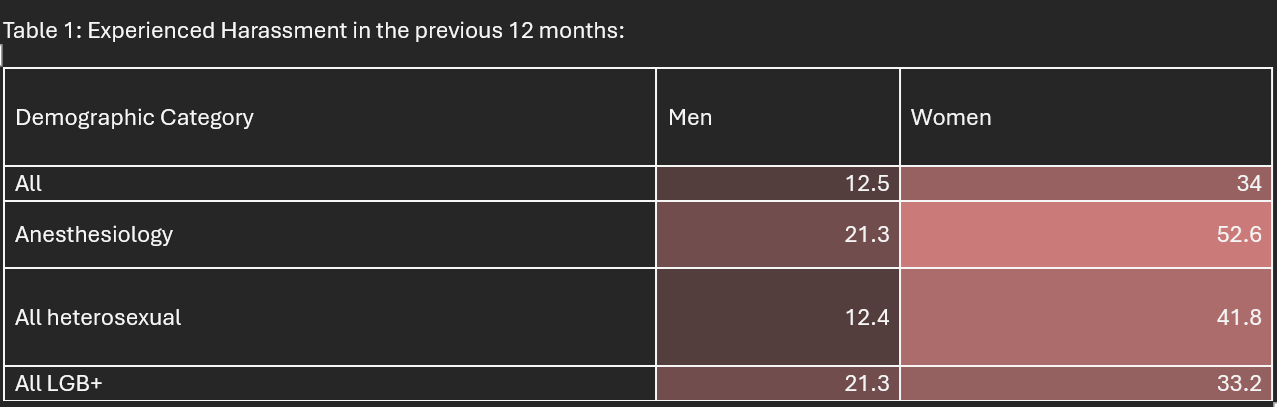

Depending on your identity, you may not have been surprised by the 2022 AAMC report titled “Understanding and Addressing Sexual Harassment in Academic Medicine.”(1) This survey of faculty at academic medical centers found that most anesthesiology faculty who identify as women reported harassment during the previous 12 months, as compared to about a fifth of all men. This was significantly higher than the overall rate for all faculty in all disciplines, which also included basic science. LGB+ faculty also experience a much higher rate than heterosexual faculty. Rates for transgender faculty in any discipline and LGB+ or transgender anesthesiology faculty were not available. You can see specifics below in Table 1. Faculty in Anesthesiology and Emergency Medicine experienced the highest rate of overall harassment, as compared to other departments. (Figure 1).

This was shocking to many, but probably not to you if you’ve been mistreated at work because of your gender. Below we can see the specific makeup of harassment experienced by Anesthesiology faculty.

Table 2: AAMC 2022 Anesthesiology-specific data

This problem clearly extends far beyond condescension or aggressive treatment by surgeons or peer anesthesia providers. Over one-third of women heard sexist stories or jokes, disparaging language about all women, and were specifically put down or mistreated because of their gender. Take a moment to reflect on when you last witnessed such behavior. Unfortunately, it’s likely it was in the last year. In fact, unpublished data (mentioned in Reference #2) indicate a trend of an increase in Anesthesiology faculty experiencing sexual harassment, as compared to an overall decrease among all faculty in all departments. In 2022-23, fully 25% of Anesthesiology men and 54% of women experienced sexual harassment. As noted above, sexual minorities experience harassment at an even greater rate. Although data was unavailable for transgender providers, harassment is likely higher among this community than other sexual minorities given evidence that demonstrates this phenomenon in the general U.S. population.

After the 2022 AAMC Report, the April 2023 ASA Monitor published an article from the then-president of the Association of University Anesthesiologists, George Mashour, who made valuable points.(3) Namely, that we should take these data seriously, assume that our local department is experiencing this problem, and that we should not make assumptions about who the perpetrators are. We need more information and need to take action. Specifically, the AAMC report on faculty experiences does not encompass our trainees, students, CRNAs, administrative and research staff, technicians and others who work with us.

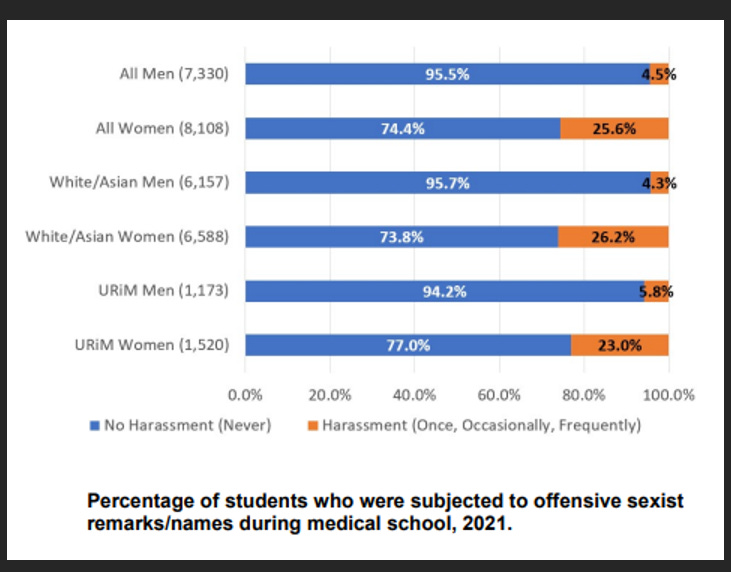

Importantly, while students report a low rate of some forms of sexual harassment (Figure 3) (4), they undoubtedly witness at least some mistreatment of Anesthesiology faculty, which may contribute to a persistently low rate of women entering our field. The AAMC report on the State of Women in Academic Medicine 2023-2024 showed that only 35% of entering residents in 2018 were women, and this increased to only 36% in 2022. (2) As an aside, the AAMC State of Women report is excellent. It brings to light many important issues beyond the scope of this piece.

What do we do about this? The AUA is working on understanding this problem through survey data and has promised a forthcoming publication. Once we understand the problem, we can better deploy countermeasures. The ASA just released a new “Statement on Harassment, Incivility and Disrespect” which makes clear that institutions should create and deploy a holistic strategic plan to eliminate these negative behaviors. (5) As the most-often victimized discipline, we should be the first to demand our institutions address this problem immediately and directly. At the individual level, we should first ensure we are not perpetrators ourselves, and then be “upstanders” and not bystanders when others are victimized. While many of us have the best intentions, the learned skill of being an “upstander” usually requires self-education, formal training, continued practice, as well as self-reflection. This begs the question, what steps will you make to become more of an “upstander”?

Figure 3: Medical Student data from the AAMC 2021 Graduation Questionnaire

Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References:

1. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM, Zhou Y. Understanding and Addressing Sexual Harassment in Academic Medicine. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2022. Available at aamc.org

2. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine 2023-2024: Progressing Toward Equity. Washington, DC: AAMC; November 2024. Available at aamc.org

3. George A. Mashour; This Is Not Acceptable. ASA Monitor 2023; 87:34 doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASM.0000925020.07308.aa

4. AAMC Data Snapshot – “October 2022 Experiences of Sexual Harassment Among Medical Students and Postdocs at U.S. Medical Schools”. Available at aamc.org