When I moved to Colorado from Maryland, I was shocked at the widespread and easy availability of legal marijuana in the state. Indeed, there appeared to me to be as many medicinal and recreational marijuana dispensaries as Starbuck locations, perhaps even more! As legalization spreads throughout the United States and much of world, this drug family, once an underground, illegal industry is on the threshold of becoming a $100 billion legal industry! 1

The January issue of Anesthesia and Analgesia has several articles devoted to the medicinal use of cannabinoids. Over the next 2-3 weeks, the PAAD will be reviewing several of them, starting with today’s basic science review.2 Because of the complexity of the receptor pharmacology of the cannabinoid system, today’s PAAD will be divided into 2 parts in order to maintain our desire to keep PAADs at 5-6 minute reads. Myron Yaster MD

Editorial

Shah S, Narouze S. Cannabis as a Therapeutic or Snake Oil? A Call for Critical Appraisal of the Literature. Anesth Analg. 2024 Jan 1;138(1):2-4. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006592. Epub 2023 Dec 15. PMID: 38100796.

Original article

Sideris A, Lauzadis J, Kaczocha M. The Basic Science of Cannabinoids. Anesth Analg. 2024 Jan 1;138(1):42-53. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006472. Epub 2023 Dec 15. PMID: 38100799.

“The cannabis plant has been used for centuries to manage symptoms of various ailments, including pain. Literally hundreds of bioactive chemical compounds have been identified and isolated from the cannabis plant that elicit a variety of physiological responses by binding to specific receptors and interacting with other proteins.

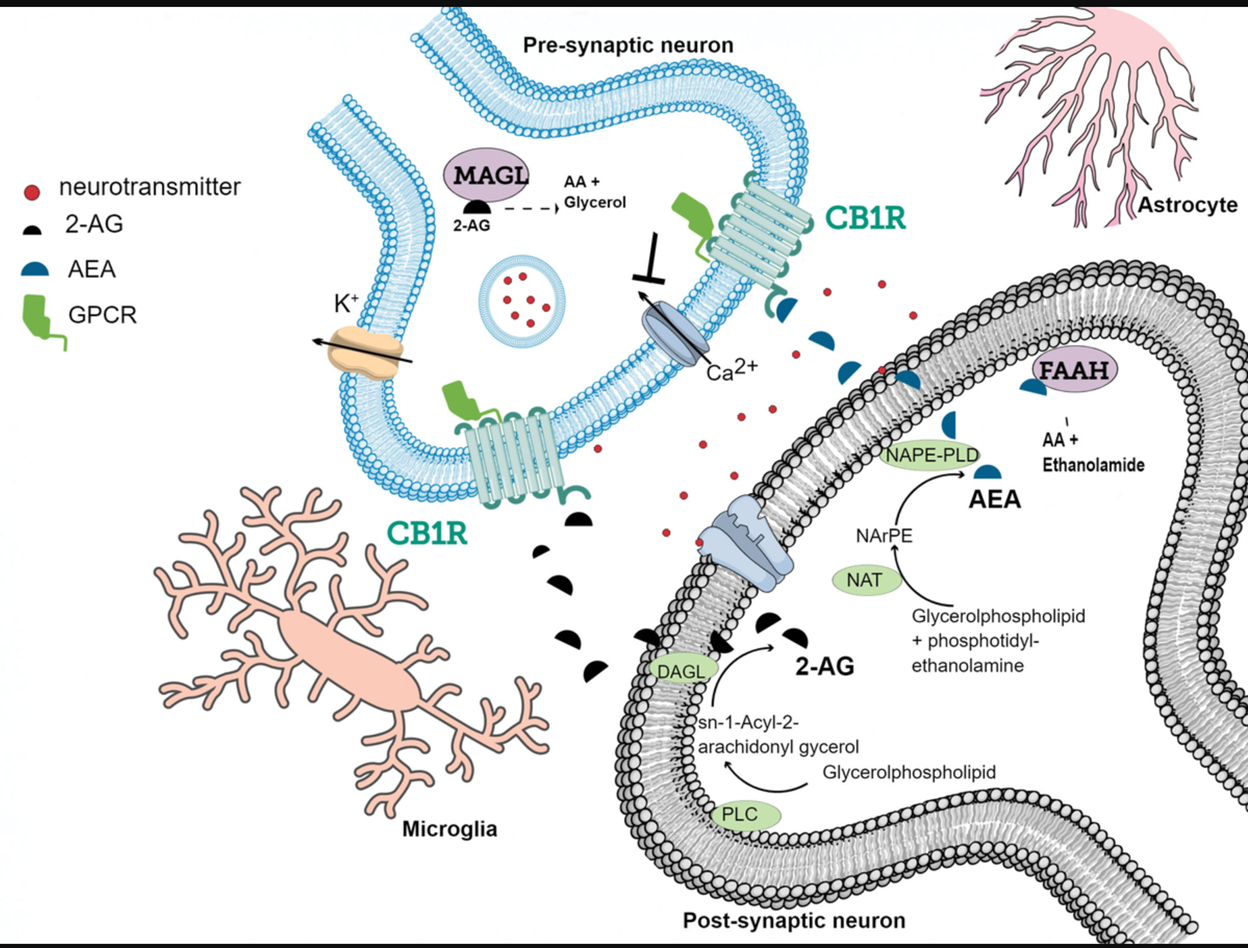

The 2 most well-known phytocannabinoids, that is, cannabinoids derived from the cannabis plant, are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) and were first discovered in the 1960s by Mechsoulam and colleagues.3 As with opioids, the presence of cannabinoid receptors means that there must be endogenous cannabinoids (endocannabinoids) as well to activate them. Arachidonoyl ethanolamide, or anandamide (AEA), and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) are the main endocannabinoids (eCBs) that have been identified to date (Figure 1). Cannabinoids, both endogenous and exogenous, inhibit adenylate cyclase by binding to G-protein-coupled receptors, the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2) that are widely distributed in the brain and periphery.2

The CB1 receptor is abundant in the central and peripheral nervous system accounting for the well-known psychotropic, analgesic, and anti-emetic effects (figure 2). On the other hand, CB2 receptors (to be discussed in more detail in the PAAD to follow) are found in in specific subpopulations of neurons within the brainstem and hippocampus and in peripheral immune cells that are induced after injury and inflammation. Activation of CB2 on immune cells largely produces anti-inflammatory effects.2,4

We think most of you know and are familiar with alpha-2 adrenergic receptors and their agonists and antagonists. When alpha-2 agonists bind to the alpha-2 receptor they produce a negative feedback loop to regulate the presynaptic release of neurotransmitters. The endocannabinoid system works in a similar way but with a twist. “eCBs (AEA and 2-AG) are synthesized “on demand” in a rapid enzymatic process within the postsynaptic neuron by activity-dependent cleavage of phospholipid precursors. The synthesized eCBs then travel retrogradely where they bind to CB1 receptors located in the presynaptic terminal. How does the process end? 2-AG is inactivated by monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) and AEA is inactivated by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH).

Through G i/o -protein-coupled signaling mechanisms, CB1 receptor activation decreases the probability of neurotransmitter release through inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels or activation of inwardly rectifying potassium channels.”2,5 Because CB1 receptors can be found on GABAergic, glutamatergic, serotonergic, opioid, and dopaminergic neurons, “neuronal eCB signaling is an elegant and tightly coordinated neuromodulatory system, effectively functioning as a “circuit breaker”.6”1,2

There are 3 main species of the plant, C. sativa , C. indica , and C. ruderalis , though this taxonomy remains controversial.7 Cannabidiol (CBD) is the nonenzymatic oxidative breakdown product of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), seen in aged Cannabis, and has about 25% of the potency of THC. CBD is not psychoactive, but it may exhibit antianxiety effects, mitigates the development of psychosis in heavy THC users, and may even exhibit antidepressant effects.7 Of course, it has also been FDA-approved and commercialized for the treatment of intractable seizures.

The chemical heterogeneity of the cannabis plant constituents extends to terpenes and flavinoids, which have their own distinct pharmacological profiles and mechanisms of action that engage non-cannabinoid receptor pathways. Indeed, “It has been proposed that there may be synergy among the various constituents of the plant in what is broadly referred to as an “entourage” effect.”2,7 In many ways the entourage effect “is akin to a symphony, in which many musicians support and harmonize the melody provided by the soloists.”7 (It is beyond the scope of today’s PAAD to go into greater detail about the main species of the plant. However, for those who want to delve more deeply into this, we highly recommend the short and entertaining article by Piomelli and Russo7. Indeed, one of our favorite quotes from the article may settle some confusion: “the sativa/indica distinction as commonly applied in the lay literature is total nonsense and an exercise in futility.”7)

Finally, because marijuana remains a DEA class 1 regulated drug, there “is no uniform quality control of potency or purity of cannabis products and a paucity of research to inform the practitioner and patient of correct dosing. Any recommendations for a specific cannabis strain or phytochemical ratio to ameliorate symptoms such as pain are based on anecdotes and few well controlled clinical trials at best. More research in preclinical and clinical contexts is warranted to identify optimal combinations of these chemicals, routes, and doses of cannabis constituents for specific indications.8,2,9-11

Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

1. Shah S, Narouze S. Cannabis as a Therapeutic or Snake Oil? A Desperate Call for Critical Appraisal of the Literature. Anesthesia and analgesia 2024;138(1):2-4. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000006592.

2. Sideris A, Lauzadis J, Kaczocha M. The Basic Science of Cannabinoids. Anesthesia and analgesia 2024;138(1):42-53. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000006472.

3. Mechoulam R, Parker LA. The endocannabinoid system and the brain. Annu Rev Psychol 2013;64:21-47. (In eng). DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143739.

4. Turcotte C, Blanchet MR, Laviolette M, Flamand N. The CB(2) receptor and its role as a regulator of inflammation. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016;73(23):4449-4470. (In eng). DOI: 10.1007/s00018-016-2300-4.

5. Araque A, Castillo PE, Manzoni OJ, Tonini R. Synaptic functions of endocannabinoid signaling in health and disease. Neuropharmacology 2017;124:13-24. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.06.017.

6. Katona I, Freund TF. Endocannabinoid signaling as a synaptic circuit breaker in neurological disease. Nat Med 2008;14(9):923-30. (In eng). DOI: 10.1038/nm.f.1869.

7. Piomelli D, Russo EB. The Cannabis sativa Versus Cannabis indica Debate: An Interview with Ethan Russo, MD. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2016;1(1):44-46. (In eng). DOI: 10.1089/can.2015.29003.ebr.

8. Anand U, Pacchetti B, Anand P, Sodergren MH. Cannabis-based medicines and pain: a review of potential synergistic and entourage effects. Pain management 2021;11(4):395-403. (In eng). DOI: 10.2217/pmt-2020-0110.

9. Moore RA, Fisher E, Finn DP, et al. Cannabinoids, cannabis, and cannabis-based medicines for pain management: an overview of systematic reviews. Pain 2021;162(Suppl 1):S67-s79. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001941.

10. Haroutounian S, Arendt-Nielsen L, Belton J, et al. International Association for the Study of Pain Presidential Task Force on Cannabis and Cannabinoid Analgesia: research agenda on the use of cannabinoids, cannabis, and cannabis-based medicines for pain management. Pain 2021;162(Suppl 1):S117-s124. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002266.

11. Fisher E, Moore RA, Fogarty AE, et al. Cannabinoids, cannabis, and cannabis-based medicine for pain management: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Pain 2021;162(Suppl 1):S45-s66. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001929.