In today’s edition of the PAAD, I’m reposting my very first PAAD first published on March 18, 2021. The late Dr. Ron Litman who started the PAAD and in whose memory we maintain it, asked me to revisit the classic paper by Halliday and Segar.1 Many, really most, of you have joined the PAAD community long after this was first posted and it is as relevant today as it was back in 2021. In today’s PAAD, I will review the origins of the 4-2-1 rule that has governed perioperative and hospital-based maintenance fluid therapy in children for decades.

Original article

Holliday MA, Segar WE. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics. 1957 May;19(5):823-32. PMID: 13431307.

In this classic paper, Holliday and Segar proposed a simple-to-use formula that relates to the average caloric expenditure of a child of a given weight in kg:

Infant up to 10 kg expend 100 kcal/kg;

Children 10 - 20 kg expend 1000 kcal + 50 kcal/kg:

Children > 20 kg expend 1500 kcal + 20 kcal/kg.

The allowance of 50 mL/kg/24 hours will replace insensible losses and 66.7 ml/kg/24 hours will replace urinary losses so that 110 to 120 mL/100 kcal expended every 24 hours meets appropriate water maintenance needs. The math was further simplified as the “4-2-1 rule” and it is still used by anesthesiologists (and pediatricians) to this day. At the end of the original article, Holliday and Segar conclude that daily electrolyte requirements for Na, Cl, and K are 3.0, 2.0, and 2.0 mEq/100 cal/day, respectively.

In a very important and related paper, Anne Bailey2 and her colleagues point out “that these electrolyte requirements are theoretically met by the hypotonic maintenance fluid more commonly used in hospitalized children in the United States today, namely 5% dextrose with 0.2% normal saline. In Holliday and Segar’s original conclusions, it was emphasized that “these figures provide only maintenance needs for water. It is beyond the scope of this paper to consider repair of deficits or replacement of continuing abnormal losses of water.” Bailey adds, “Unfortunately, clinicians may often extrapolate the “4-2-1 rule” and the accompanying hypotonic solutions to clinical situations where they may not be appropriate and could, in fact, be harmful.”

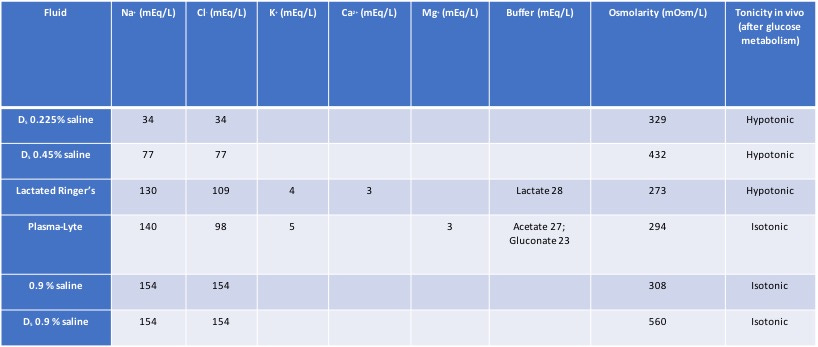

Bailey et al. are spot on right! In the OR, we should ONLY be infusing isotonic solutions like Plasmalyte, Normosol, Ringers Lactate, or (ab)normal saline. (I call it abnormal saline because there is nothing “normal” about it: it contains too much chloride and can produce a hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis). I believe we should always discontinue hypotonic solutions in the OR to avoid hyponatremia, a completely avoidable iatrogenic complication.3

Because NPO times, particularly for liquids, continue to drop (it’s pretty clear it will or is already dropping to only an hour), and the risks of too much crystalloid are becoming increasingly clear, perhaps we need to rethink how much crystalloid we are infusing in the OR completely. We are almost certainly giving too much and in this era of ERAS, we probably should reconsider how we do this.

A last comment: As many of you know I think of the PAAD as a terrific teaching tool for residents, fellows and other learners. Surprisingly, many of the trainees that I used to work with simply did not know the composition of most IV fluids. So, during the “boring” parts of an anesthetic why don’t you ask them to construct a table of what’s in IV fluids. This is what it should look like when done:

Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

1. Holliday MA, Segar WE. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19(5):823-32. (In eng).

2. Bailey AG, McNaull PP, Jooste E, Tuchman JB. Perioperative crystalloid and colloid fluid management in children: where are we and how did we get here? Anesthesia and analgesia 2010;110(2):375-90. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b6b3b5.

3. Moritz ML, Ayus JC. Prevention of hospital-acquired hyponatremia: a case for using isotonic saline. Pediatrics 2003;111(2):227-30. (In eng). DOI: 10.1542/peds.111.2.227.

In 2009, I had a handout that compared the solutions for use in the OR. I had to fight the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee to allow me to use Plasmalyte outside the heart room because it was a few cents more expensive than NS. Of note was that fact that at the time, it was the common misconception that only NS was compatible with blood or blood products. So at the bottom of my excel spreadsheet that was very similar to yours, I noted the following. "Package insert for Plasmalyte-A injection pH 7.4: The indications and usage section of the package insert of Plasmalyte-A injection pH 7.4 states that the solution is equally compatible to normal saline with blood and components. Plasmalyte-A injection pH 7.4 can be used as a priming solution for blood components, and may be added to or used with blood components through the same line, and may be used as a diluent for blood components."

"Poisonous for children!". That was the label, in large red letters, that started appearing next to bags of "half normal saline" on some Australian children's wards 10 years ago. Since then hypotonic fluids have disappeared from our wards. It has been a slow journey since the 1950's Halliday paper mentioned by Myron. The journey has been controversial and tragic for those children that died due to well-meaning staff prescribing a "poisonous fluid". From the beginning there was doubt that 0.2% saline was the right fluid for children. Some suggested isotonic fluid would be better. Others feared this would lead to hypernatremia. A compromise was reached. We feared going all the way, so we went half-way and half normal saline was born. Alas, children still died from iatrogenic hyponatremia. The medical community couldn't agree on isotonic fluid. The evidence was not quite there yet.

As a researcher we start thinking we will make great discoveries and change the way we care for children; spectacularly improving outcomes. Alas you soon realize that you are lucky if you make one discovery in your lifetime that has any impact - let alone spectacular impact. If you're really lucky you may make two. For me it was the PIMS trial published in the Lancet in 2015 (McNab S, Duke T, South M, et al. 140 mmol/L of sodium versus 77 mmol/L of sodium in maintenance intravenous fluid therapy for children in hospital (PIMS): a randomized controlled double-blind trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9974):1190–1197), though even then "discovery" may be an overstatement. We randomized hundreds of children across the hospital to maintenance with isotonic or half normal saline. The hospital was full of fluid bags wrapped in black plastic. Every ward, every nurse and every junior staff member was involved in the trial. In those days such trials were actually feasible! Sure enough, those with isotonic fluid got less hyponatremia and perhaps fewer nasty complications. Doh... Virtually overnight practice changed across Australia. Trials change practice when we are at the cusp of evidence; just enough to flip things. This was such a trial. We alone didn't change practice, we just gave the final nudge. A couple of years afterwards the American Academy of Pediatrics published the guideline recommending isotonic fluid. (Feld et al Pediatrics (2018) 142 (6): e20183083. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3083). Hopefully the "poison" labels are no longer needed anywhere and half saline has gone for good.

One last part of the story. Switching to isotonic fluid didn't completely eliminate iatrogenic hyponatremia. Sick children have elevated levels of ADH, and are at risk of hyponatremia, more so than adults. The 4:2:1 rule is fine for well children but too much water for sick children. We may have got rid of half normal saline but the 4:2:1 error persists; and is still harming children.