Rescuing failed direct laryngoscopy in children

Myron Yaster MD, Melissa Brooks Peterson MD, El Jefe MD, and Francis Veyckemans MD

One of my favorite teaching aphorisms is this:

“Bad technique makes an easy airway difficult, and good technique makes a difficult airway easy.”

It’s a truth that resonates in every pediatric OR, PICU, and ED. Airway management is high-stakes. It demands precision, poise, and most importantly—preparation. No matter how experienced or talented you are, over the course of your career, you will encounter a child who simply cannot be intubated using standard direct laryngoscopy (DL). When that moment comes—and it will—what you do next is absolutely critical.

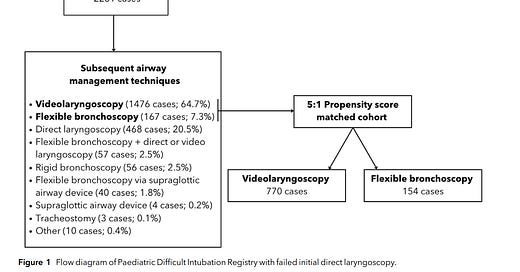

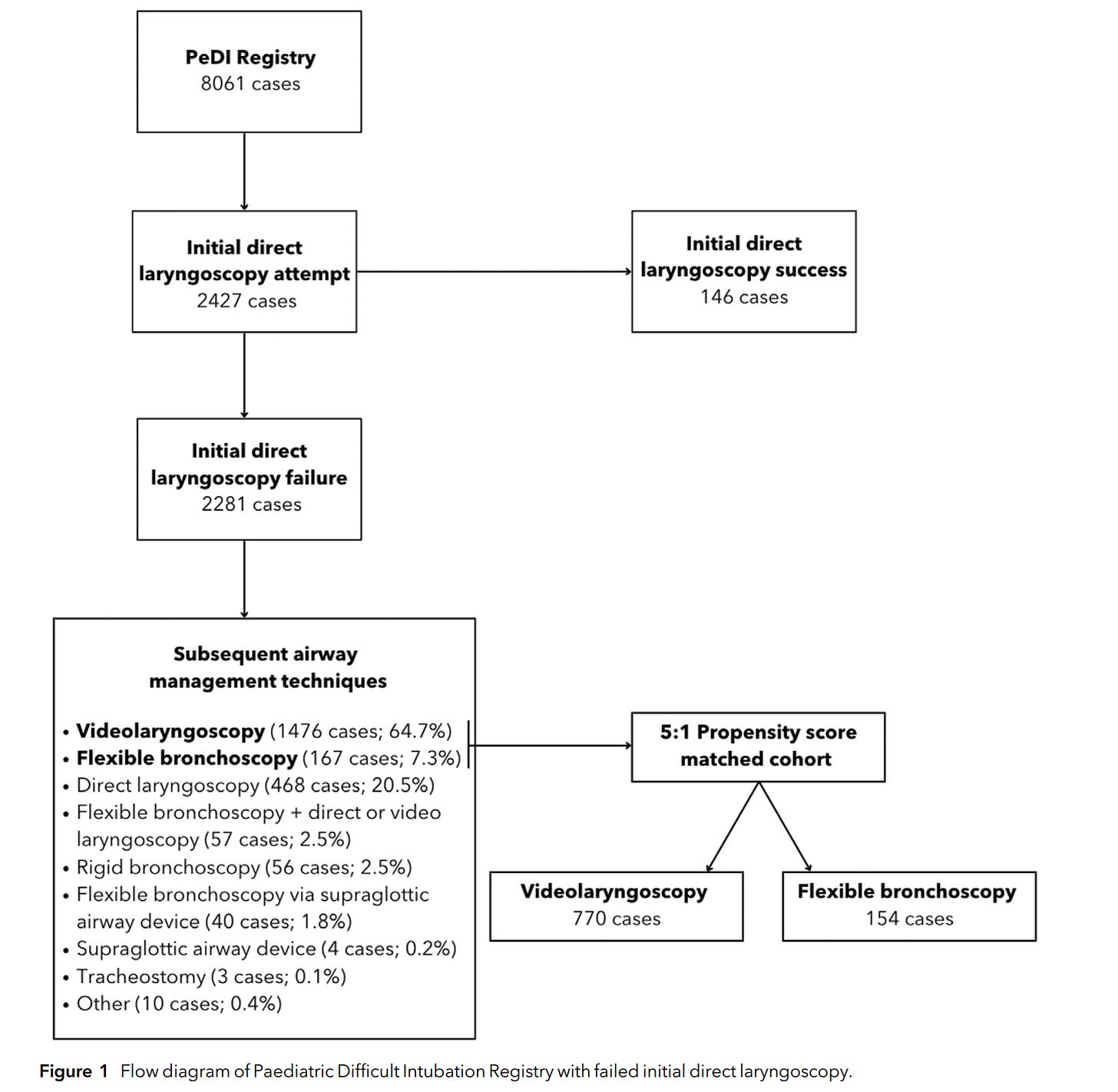

Enter the Pediatric Difficult Intubation (PeDI) Registry, a living database that has revolutionized our understanding of pediatric airway management. What began as a special interest group of the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia has grown into an international collaborative spanning 43 institutions and thousands of high-risk airway cases. Its contributions have shaped guidelines, influenced training, and—most importantly—saved lives.1-6 In today’s PAAD7 (and its accompanying editorial8), Stein et al. add another important piece to the puzzle. Their study, using over a decade of PeDI registry data, asks a focused and practical question:

What works best when direct laryngoscopy fails—videolaryngoscopy (VL) or flexible bronchoscopy (FB)? Myron Yaster MD

Original article

Stein ML, Nagle JH, Templeton TW, Staffa SJ, Flynn SG, Bordini M, Nykiel-Bailey S, Garcia-Marcinkiewicz AG, Padiyath F, Matuszczak M, Lee AC, Peyton JM, Park RS, von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Olomu PN, Hunyady AI, Matava C, Fiadjoe JE, Kovatsis PG; PeDI Collaborative. Comparing videolaryngoscopy and flexible bronchoscopy to rescue failed direct laryngoscopy in children: a propensity score matched analysis of the Pediatric Difficult Intubation Registry. Anaesthesia. 2025 Jun;80(6):625-635. doi: 10.1111/anae.16576. Epub 2025 Mar 20. PMID: 40113331.

Editorial

Evans MA, Caruso TJ. Rescuing failed direct laryngoscopy in children: one size does not fit all. Anaesthesia. 2025 Jun;80(6):621-624. doi: 10.1111/anae.16577. Epub 2025 Mar 21. PMID: 40114500.

What Did They Find?

Stein et al.7 analyzed 2,281 cases where DL was attempted and failed. The vast majority of clinicians turned to videolaryngoscopy as the next step—used in 65% of cases—while flexible bronchoscopy was used in just 7%. After 5:1 propensity score matching, the success and complication rates of VL and FB were similar for the overall cohort.

But here’s where it gets interesting:

In children under 5 kg, flexible bronchoscopy had a significantly higher eventual success rate than videolaryngoscopy (90% vs. 71%). First-pass success also trended higher (62% vs. 43%, p = 0.061).

These small infants also endured more airway attempts and had higher complication rates. This subgroup analysis is clinically meaningful, particularly for neonatal anesthesiologists and intensivists.

Evans and Caruso, in their editorial, interpret these findings with the insight of seasoned clinicians.8 They rightly underscore the importance of maintaining proficiency in flexible bronchoscopy, despite the dominance of videolaryngoscopy in most settings. They explore plausible reasons why FB may succeed more often in small infants—from better alignment with anterior airway anatomy to reduced trauma over repeated attempts with VL. They also point out that VL, especially with hyperangulated blades, can introduce technical complexity that may limit success in the smallest patients.

Their conclusion? One size does not fit all. And we couldn’t agree more.

As discussed in previous PAADs, videolaryngoscopy is the better technique to use for the first attempt at intubation in children < 5 kg and/or in children with a known difficult airway. Regardless of technique, supplemental oxygen should always be provided for apneic oxygenation in all of these patients during intubation. Further, there are basically 2 types of videolaryngoscopy blades, standard type (Miller or Macintosh) blades and hyperangulated blades. Not surprisingly and much like we find in our practice, Stein et al. found higher success with standard blades than with the hyperangulated blades, particularly in children < 5 kg. Finally, although both videolaryngoscopy and flexible bronchoscopy are good choices for the rescue of failed direct laryngoscopy, flexible bronchoscopy was associated with higher eventual tracheal intubation success than videolaryngoscopy in children weighing < 5 kg.

Interestingly, the quick use of a supraglottic airway was uncommon and intubation using flexible bronchoscopy via a supraglottic airway device was rare. We are unsure why this is. Nevertheless, it is pretty clear that videolaryngoscopy with Miller or Macintosh blades remains the instrument of choice in the event of an unanticipated difficult airway for the majority of children given its ergonomics, speed and familiarity.

What the Article and Editorial Didn’t Say—But Should

Let’s be honest and as we’ve stressed in several previous PAADs: evidence is only half the battle. The real challenge lies in implementation.

What does this mean for your practice, your team, your institution?

These are the conversations we need to have. Evidence-based medicine only works if it’s implemented effectively. So let’s ask the real-world questions:

1. What’s in your Difficult Airway Cart?

Do you have both standard and hyperangulated VL blades in neonatal sizes? Do you stock fiberoptic bronchoscopes that are small enough (and functional enough) to use with ETTs <3.0 mm? Can they suction? Is your cart easy to locate, consistently restocked, and available outside the OR (e.g., in the NICU or ED)?

2. Where is it? And who knows how to use it?

The best equipment is useless if no one can find it—or worse, no one knows how to use it. Rare events demand muscle memory, not scrambling. Who’s trained on FB? When was the last time you scoped a patient?

This brings us to the team…

3. Do you have a Difficult Airway Response Team (DART)?

If you call for help in a difficult airway, who comes? Is there a protocol? Do they bring the right equipment and expertise? Do they come at 2 AM on a Sunday? A DART—like a Code Blue team—should be institutionalized, not improvised.

4. What’s your maintenance-of-skill strategy?

Flexible bronchoscopy is not a “once trained, forever skilled” technique. It requires deliberate practice, regular simulation, and feedback. Yet in many centers, it’s rarely used. That’s dangerous. As Evans and Caruso note, it has a steep learning curve—and yet, in <5 kg infants, it may be your best bet for success.

5. Are you optimizing technique—or repeating failure?

Multiple attempts at intubation don’t just increase time—they increase trauma, edema, and hypoxia. VL has a learning curve too, especially with hyperangulated blades that require preloaded ETTs with exaggerated curvature. In contrast, standard VL blades—Miller or Macintosh—were shown in the study to have higher first-pass and eventual success rates compared to hyperangulated blades, especially in small infants.

The Path Forward: Science + Systems

This study gives us data. The editorial gives us context. But you—and your department—must provide the infrastructure.

Let’s advocate for:

Standardized equipment and carts across units

Regular multidisciplinary simulation

24/7 team-based response protocols

Tracking and review of real-world airway outcomes

Tailored training for VL and FB, including hybrid techniques

Perhaps most of all, let’s ensure that we don’t just “prefer” a device because it’s easy or familiar—but that we choose it deliberately, based on patient-specific anatomy, prior history, and procedural logistics.

Conclusion

VL and FB are not competitors—they are complementary tools. The real question is not which is better, but which is better for this patient, right now, in your hands, with your team. That’s the art of pediatric anesthesiology. Stein et al. remind us that evidence matters. Evans and Caruso remind us that context matters. But we’ll remind you that execution matters most.

So stock your carts, drill your team, sharpen your technique, and never stop learning. Because one day—maybe today—that child who "can’t be intubated" will be yours. Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday Reader Response.

References

1. Fiadjoe JE, Nishisaki A, Jagannathan N, Hunyady AI, Greenberg RS, Reynolds PI, Matuszczak ME, Rehman MA, Polaner DM, Szmuk P, Nadkarni VM, McGowan FX, Jr., Litman RS, Kovatsis PG: Airway management complications in children with difficult tracheal intubation from the Pediatric Difficult Intubation (PeDI) registry: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 37–48

2. Engelhardt T, Fiadjoe JE, Weiss M, Baker P, Bew S, Echeverry Marín P, von Ungern-Sternberg BS: A framework for the management of the pediatric airway. Paediatr Anaesth 2019; 29: 985–992

3. Garcia-Marcinkiewicz AG, Kovatsis PG, Hunyady AI, Olomu PN, Zhang B, Sathyamoorthy M, Gonzalez A, Kanmanthreddy S, Gálvez JA, Franz AM, Peyton J, Park R, Kiss EE, Sommerfield D, Griffis H, Nishisaki A, von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Nadkarni VM, McGowan FX, Jr., Fiadjoe JE: First-attempt success rate of video laryngoscopy in small infants (VISI): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020; 396: 1905–1913

4. Disma N, Asai T, Cools E, Cronin A, Engelhardt T, Fiadjoe J, Fuchs A, Garcia-Marcinkiewicz A, Habre W, Heath C, Johansen M, Kaufmann J, Kleine-Brueggeney M, Kovatsis PG, Kranke P, Lusardi AC, Matava C, Peyton J, Riva T, Romero CS, von Ungern-Sternberg B, Veyckemans F, Afshari A: Airway management in neonates and infants: European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care and British Journal of Anaesthesia joint guidelines. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2024; 41: 3–23

5. Sequera-Ramos L, Laverriere EK, Garcia-Marcinkiewicz AG, Zhang B, Kovatsis PG, Fiadjoe JE: Sedation versus General Anesthesia for Tracheal Intubation in Children with Difficult Airways: A Cohort Study from the Pediatric Difficult Intubation Registry. Anesthesiology 2022; 137: 418–433

6. Burjek NE, Nishisaki A, Fiadjoe JE, Adams HD, Peeples KN, Raman VT, Olomu PN, Kovatsis PG, Jagannathan N, Hunyady A, Bosenberg A, Tham S, Low D, Hopkins P, Glover C, Olutoye O, Szmuk P, McCloskey J, Dalesio N, Koka R, Greenberg R, Watkins S, Patel V, Reynolds P, Matuszczak M, Jain R, Khalil S, Polaner D, Zieg J, Szolnoki J, Sathyamoorthy K, Taicher B, Riveros Perez NR, Bhattacharya S, Bhalla T, Stricker P, Lockman J, Galvez J, Rehman M, Von Ungern-Sternberg B, Sommerfield D, Soneru C, Chiao F, Richtsfeld M, Belani K, Sarmiento L, Mireles S, Bilen Rosas G, Park R, Peyton J: Videolaryngoscopy versus Fiber-optic Intubation through a Supraglottic Airway in Children with a Difficult Airway: An Analysis from the Multicenter Pediatric Difficult Intubation Registry. Anesthesiology 2017; 127: 432–440

7. Stein ML, Nagle JH, Templeton TW, Staffa SJ, Flynn SG, Bordini M, Nykiel-Bailey S, Garcia-Marcinkiewicz AG, Padiyath F, Matuszczak M, Lee AC, Peyton JM, Park RS, von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Olomu PN, Hunyady AI, Matava C, Fiadjoe JE, Kovatsis PG: Comparing videolaryngoscopy and flexible bronchoscopy to rescue failed direct laryngoscopy in children: a propensity score matched analysis of the Pediatric Difficult Intubation Registry. Anaesthesia 2025; 80: 625–635

8. Evans MA, Caruso TJ: Rescuing failed direct laryngoscopy in children: one size does not fit all. Anaesthesia 2025; 80: 621–624