From Dr. Bob Spear (retired), San Diego

I would like to preemptively apologize to whomever once quizzed me, “what do you call an anesthesiologist in a suit?” Answer: “The defendant”.

The recent PAADs on “Error Traps”, a phrase that is new to me, are basically highlighting the most likely ways that we as intensivists or anesthesiologists can practice our difficult craft while avoiding preventable and often tragic outcomes. Besides the basic anesthesiologist rules (2 laryngoscopes that work, ETT, mask, syringes of drugs, oxygen tank, 2-3 syringes of flush, etc), indulge me in my couple-three or so of pitfalls that I endeavored to avoid while transporting patients. I will admit that there are occasional nuanced situations that one might not agree with me…but in general…here goes.

1. ETT dislodgment: When moving an intubated patient, I was taught and subsequently taught others to unhook the tubing from the ETT when moving the patient…always (ok PEEP 20 cmH20, we can maybe think about this). Most, or maybe many non-anesthesiologists would hold the tube itself and attempt to move in tandem (nearly impossible) with the moving patient as said patient was transferred onto transport gurney (trolley?) from PICU bed. ALWAYS disconnect the ETT from the ventilator/Ambu bag….then move the patient, then re-connect…then disconnect again since the first move is often interrupted by “wait…the foley/warming blanket/fill in blank”. If the tubing to the ventilator gets snagged, the ETT gets “tromboned out” (verb) and in a split second can be moved above the glottis. I was always amused to hear a PICU fellow tell a peds resident, “you know why Dr. Spear does that, don’t you?” Peds resident would pause….fellow would then explain, “he doesn’t want to put on a suit”.

2. For short transports to CT (or wherever) when no vasoactive infusions are involved, I would ALWAYS disconnect IVs, CVP and flush w heparin. Tubing is your enemy. When returning to the PICU 30-40 min later, 1) Move the patient after unhooking the ETT, 2) Re-attach the ETT, 3) hook up your IV, CVP tubing and resume care. CVPs get ripped out by tubing, they never fall out, and, of course, they are almost never monitored in such cases…

3. What if the patient has a vasoactive infusion(s)? First, a few questions should be asked. Why is the patient on epi 0.03 mcg/kg/min (after 6-7 yrs of retirement {phrase “retirement now co-opted by Formula 1 car that has crashed or broken down} please forgive me if my units of measurement are erroneous…my brain has added things like ‘covering the middle in pickleball if my partner is covering the line’…one’s brain capacity is finite, storage needs differ with time). Typically, the story goes like this. PICU fellow says, “they don’t really need the epi”. Me: “for this MRI, I will probably find out if they need epi at some point, or I will be lucky if I find out they don’t”. Upon further review…the neuro consult suggested the Brain MRI, most likely falling into the category of “The Endless Acquisition of Data” that could be acquired a day or two later when epi has been discontinued. Me as PICU doc to neurologist: “Would it be ok if we did the MRI tomorrow or next day?” Neurologist: “Absolutely, we just wanted a baseline”. Sarcastic PICU fellow says to peds resident, “he doesn’t want to go downtown (courthouse) and wear a suit for 3-4 weeks…

4. Substitute PEEP of 8cm H20 for epi above.

5. I promise, if you haven’t abandoned this diatribe yet, that #5 is the finale (I know, I said couple-three). When moving a patient, everyone (100% plus) prepares to “MOVE ON THE COUNT OF THREE”. Unfortunately, 50% of said movers move AS the word “THREE “ is spoken, 50% of movers move AFTER the word “THREE” is spoken. In reality, part of the patient is moved at 2.5s, part of the patient is moved at 3.5s. (See #1 regarding degree of difficulty in trying to move patient with ETT attached as person holding the ETT might be a member of the 2.5s club, or perhaps the 3.5s club).

5.5 Bonus comment. When movers are in short supply, they are best allocated to head, shoulders-torso and then hips. With apologies to whomever said, “we need someone for the feet”, I was being unnecessarily sarcastic in saying, “don’t worry about the feet, they’re attached”.

From Phil Carullo, Rebecca Nause-Osthoff, Rebecca Margolis, Erin Conner and Jemma Kang:

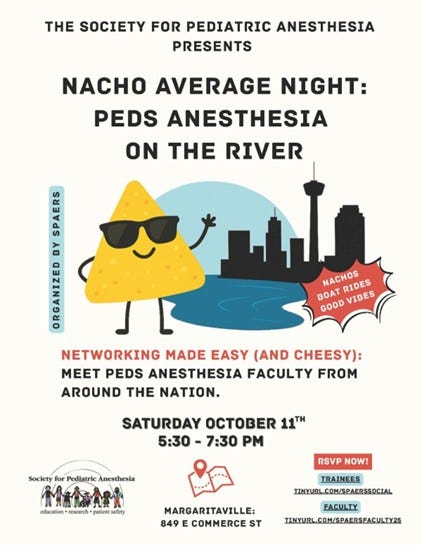

We wanted to let PAAD readership know about some great activities coming up surrounding the SPA/ASA meetings in San Antonio. The SPA Education Resident & Student (SPAERS) Subcommittee supports medical students and residents exploring pediatric anesthesiology through mentorship, scholarships, and programming. Join us at ASA for trainee-focused events, including “Nacho Average Night: Peds Anesthesia on the River” on Saturday, October 11, 2025 (5:30–7:30 PM).

We need faculty volunteers and more trainee’s welcome! RSVP is required.

Trainee Sign Up: tinyurl.com/spaerssocial

Faculty Sign up: tinyurl.com/spaersfaculty25

From Scientific American daily newsletter

You’re unlikely to open a medicine cabinet in the U.S. without seeing a bottle of Tylenol, the brand name of a pain reliever and fever reducer also sold generically as acetaminophen (paracetamol outside of the U.S.).

Yesterday, President Trump and Health and Human Services Secretary RFK, Jr., said that acetaminophen (known commonly by the brand name Tylenol) caused autism in kids whose moms had taken the drug while pregnant. Those statements go against the most conclusive scientific evidence to date (for a detailed breakdown of the safety of Tylenol during pregnancy and autism, I recommend this excellent explainer).

Why this matters: Some 52 million consumers use a product containing acetaminophen every week in the U.S, according to one health care trade association. The drug has been shown to be safe and effective and is the only over-the-counter pain medicine recommended by doctors during pregnancy. Controlling a fever and infections during pregnancy is vital to preventing harm to the fetus—uncontrolled fevers during pregnancy increase the risk of autism.

Why this is interesting: Despite its widespread use, the precise mechanism of action of the drug—the molecular explanation for how it blocks pain and fever—is still somewhat of a mystery. One hypothesis is that acetaminophen prevents the formation of prostaglandins, substances that can heighten pain and drive inflammation and fever. The second hypothesis is that the drug stops the production of endogenous cannabinoids, chemicals involved in the pain response.