From Steven L. Shafer MD on vocacapsaicin Note Dr. Shafer was the first author of the vocacapsicin article we reviewed.

Thank you for the shout out! Developing new drugs is really hard. I’ve been working on vocacapsaicin since 2016. If it were only a matter of science vocacapsaicin would be a slam-dunk.

The problem is that pharmaceutical companies are reluctant to invest in post-operative pain management. The paper in Anesthesiology (and a similarly promising study in TKA, which is the holy grail of postoperative analgesic research) represents about $150 million dollars of investment. We need about that to complete phase 3 and get the drug approved.

The attention generated by our paper in Anesthesiology, including shout-outs like the one you just gave us, is very helpful. I think we will be able to get this across the finish line. If we can do that, it will be game-changing for postoperative pain management.

I think it will also be game changing for chronic pain management (e.g., cancer pain, chemotherapy induced neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, CRPS, etc). C fibers have a central role in all of these pain states. It is likely that analgesia from vocacapsaicin injection lasts >> 2 weeks. We stopped the study at 2 weeks because that is about the duration of moderate to severe pain after bunionectomy. However, the mechanism of action is the same as Qutenza. We know that Qutenza analgesia can last for months – basically the time it takes for c fibers to regenerate into tissue.

Thus, I think this is a very big deal. Since it doesn’t affect sodium channels, there is no loss of touch, proprioception, or motor strength.

Lastly, opioid cessation was very real. We reproduced that finding in TKA (although they have more pain, so they continue taking opioids a lot longer.

There is a lot of BS about “opioid-free” and “opioid-sparing” anesthesia. I think those concepts are bogus. Who cares if you can do an “opioid-free” inguinal hernia repair? Other than as measure of analgesic efficacy, who cares if a subject takes 4 vs. 8 oxycodone tablets after surgery?

Opioids have a role in perioperative analgesia and post-operative analgesia when moderate to severe pain is expected. Eliminating opioids is a mirage. I think it is also cruel to patients. The goal is to provide sufficient analgesia by other mechanisms, so patients don’t need a lot of opioid (avoiding opioid related AEs), and reliably cease taking opioids within a few days.

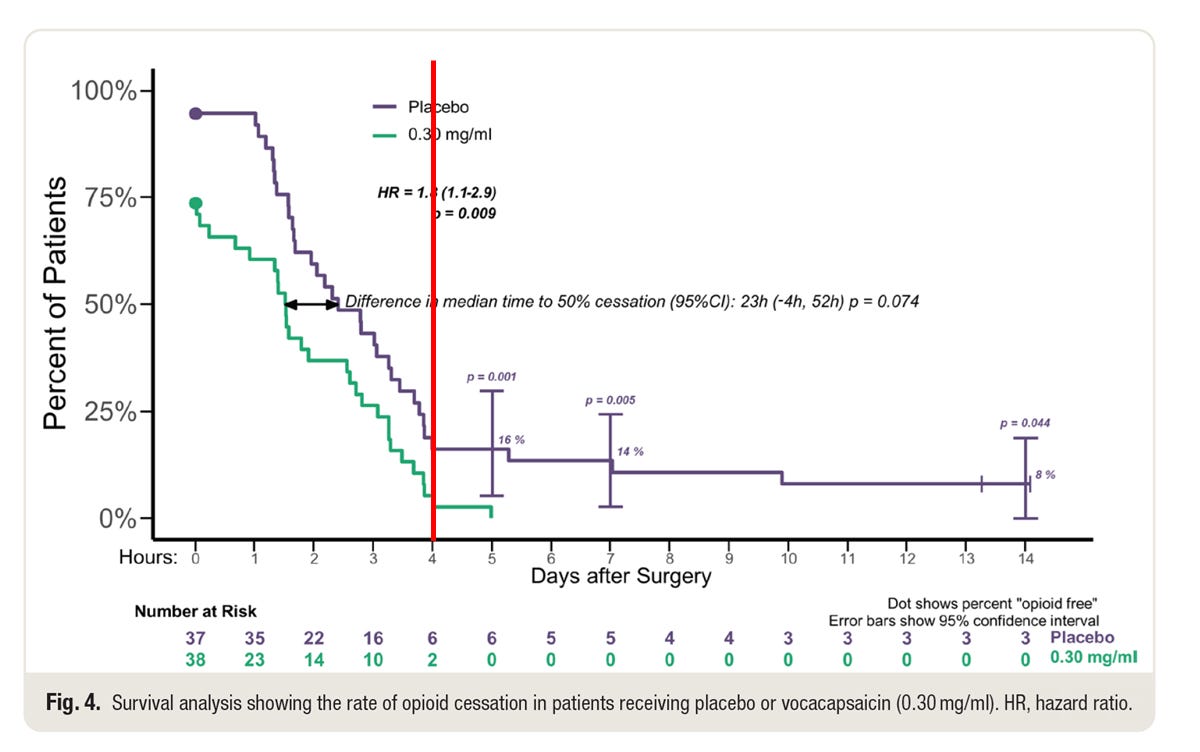

This is figure 4 from the paper, with an additional red line at 96 hours.

The study withheld NSAIDs and acetaminophen for 96 hours after surgery. Patients had access to opioids if requested, of course. That study design is necessary to assess both pain and opioid requirement.

All but 2 patients in the vocacapsaicin group stopped taking opioids by 96 hours. That’s freaking amazing. They stopped taking opioids because they felt their pain was adequately managed by … (wait for it) … nothing. It’s not as though they stopped because they were getting acetaminophen or ibuprofen. They stopped taking opioids despite not receiving any other analgesic.

By contrast, 3 of 37 patients in the placebo were still taking opioids at the end of the two week observation period. (We have pain diaries beyond that, but we didn’t push subjects to maintain diaries beyond two weeks because that was the pre-specified duration of the study). My recollection is that one subject stopped at 3 weeks. I don’t think we know when the other two subjects stopped their opioids. Perhaps when they ran out of pills.

I think this is the right way to think about opioids. “Opioid-free” started as a marketing gimmick from Pacira. They successfully linked Exparel with public concern about the opioid epidemic. It was great marketing, but there is zero evidence that Exparel has made an iota of difference in post-operative opioid use disorder. There are also zealots (e.g., Patrice Forget) who think all perioperative opioids are unnecessary and evil. I see little difference between Patrice Forget and Barry Friedberg. Both are bonkers. I’m 100% on board with using “opioid sparing” as a measure of analgesic efficacy. However, other than as a measure of analgesic efficacy I don’t think needing less opioid per se is clinically meaningful.

The finding that most excites me is showing that patients getting vocacapsaicin cease taking opioids earlier after painful surgery. I don’t think this has been previously shown for any perioperative intervention. My hope is that post-operative pain studies will start to focus on opioid cessation, rather than on “opioid-free” or “opioid-sparing” as the clinically meaningful outcome.

PS: With capsaicin, it really is “no pain, no gain.” The initial response to capsaicin is always pain from opening the TRPV1 channel to calcium. Vocacapsaicin is no different. It requires either local anesthetic infiltration prior to injection, a nerve block, or general anesthesia. Absent any of those, nobody will thank someone for an injection of vocacapsaicin.

From Jennifer L. Chiem MD, Daniel K. Low MBBS, Steven L Lee MD MBA, Lynn D. Martin MD MBA Seattle Children’s Hospital on Complications after pediatric emergency appendectomy in the UK

We read with interest your review of the “Complications after pediatric emergency appendectomy in the UK” article1. We applaud the authors for highlighting this study, as appendectomies is one of the most common surgical procedures performed in the pediatric population. Several studies have already described racial disparity in the management of pediatric appendicitis2,3 as well as appendectomy post-operative discharge care4,5. It is a disheartening reality that racial disparities persist in a system with universal health care, such as the UK and Canada6. There are, encouragingly, trends for improving disparities in pediatric appendectomy care7,8. However, it does emphasize the responsibility of all health care leaders to look at their institution’s data to determine if disparities are present and create a process to progressively improve the system.

We reviewed our own appendectomy data at Seattle Children’s Hospital. From 1/1/2016 – 5/31/2024. We performed 3,278 appendectomy cases. We do not have a composite outcome for “morbidity,” but we reviewed the following outcomes: 30-day readmission rate and 30-day reoperation rate. The data are presented as statistical process control (SPC) charts. Special cause variation (SCV) was identified using standard rules which include: 1) 8 consecutive points above or below the mean centerline 2) a single point located outside the control limits, and 3) six consecutive points increasing or decreasing (trend up or down).9 Our 30-day readmission rate is 3.48% and our 30-day reoperation rate is 4.06%. There was no SCV when stratified by race/ethnicity. When stratified by language, there was SCV for 30-day readmission rate.

Regarding quality metrics, our post anesthesia care unit (PACU) maximum pain score mean was 3.66, with SCV noted. Our PACU post operative nausea and vomiting rescue rate was 9.52%, with SCV noted. Our PACU rescue IV opioid rate is 46.92%, with no SCV noted. Average post surgery length of stay is 2.31 days, with SCV noted. When stratified by race/ethnicity, there was no SCV for the quality metrics. When stratified by language, there was SCV for PACU rescue IV opioid rate.

Given we all have electronic medical record systems capable of capturing this data, we urge all stakeholders involved in pediatric perioperative care to ask the difficult questions and to review, trust, and use their data to do better for our community.

1. Sogbodjor LA, Razavi C, Williams K, Selman A, Pereira SMP, Davenport M; CASAP investigators; Moonesinghe SR. Risk factors for complications after emergency surgery for paediatric appendicitis: a national prospective observational cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2024 May;79(5):524-534. doi: 10.1111/anae.16184. Epub 2024 Feb 22. PMID: 38387160.

2. Kokoska ER, Bird TM, Robbins JM, Smith SD, Corsi JM, Campbell BT. Racial disparities in the management of pediatric appenciditis. J Surg Res. 2007 Jan;137(1):83-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.06.020. Epub 2006 Nov 15. PMID: 17109888.

3. Zwintscher NP, Steele SR, Martin MJ, Newton CR. The effect of race on outcomes for appendicitis in children: a nationwide analysis. Am J Surg. 2014 May;207(5):748-53; discussion 753. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.12.020. Epub 2014 Mar 12. PMID: 24791639.

4. Iantorno SE, Ulugia JG, Kastenberg ZJ, Skarda DE, Bucher BT. Postdischarge Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pediatric Appendicitis: A Mediation Analysis. J Surg Res. 2023 Feb;282:174-182. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2022.09.027. Epub 2022 Oct 26. PMID: 36308900.

5. Sullivan GA, Sincavage J, Reiter AJ, Hu AJ, Rangel M, Smith CJ, Ritz EM, Shah AN, Gulack BC, Raval MV. Disparities in Utilization of Same-Day Discharge Following Appendectomy in Children. J Surg Res. 2023 Aug;288:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2023.02.033. Epub 2023 Mar 17. PMID: 36934656.

6. Bratu I, Martens PJ, Leslie WD, Dik N, Chateau D, Katz A. Pediatric appendicitis rupture rate: disparities despite universal health care. J Pediatr Surg. 2008 Nov;43(11):1964-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.05.013. PMID: 18970925.

7. Fluke LM, McEvoy CS, Peruski AH, Shibley CA, Adams BT, Stinnette SE, Ricca RL. Evaluation of disparity in care for perforated appendicitis in a universal healthcare system. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020 Feb;36(2):219-225. doi: 10.1007/s00383-019-04585-z. Epub 2019 Oct 25. PMID: 31654109.

8. Huang N, Yip W, Chang HJ, Chou YJ. Trends in rural and urban differentials in incidence rates for ruptured appendicitis under the National Health Insurance in Taiwan. Public Health. 2006 Nov;120(11):1055-63. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.06.011. Epub 2006 Oct 2. PMID: 17011602.

9. Provost LP, Murray SK. The health care data guide: learning from data for improvement. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2011.