Priming the circuit

Jeff Feldman MD

I received this question from Dr. Marty Clayman as a Reader Response and asked Dr. Jeff Feldman, a member of the PAAD’s executive council to craft a response. It was so good that I thought it deserved its own PAAD. Myron Yaster MD

From Dr. Marty Clayman:

I’m not sure this is a comment or a question. But I really have a hard time after all these years of practice, understanding priming the circuit. If you turn on your vaporizer before you turn on your fresh gas flow, all the gas coming out will be at whatever percentage you have set the vaporizer at. And you won’t be polluting the room or anything else or wasting agent. This seems so simple and straightforward. I’m not sure why no one has talked about this before.

Dr. Jeff Feldman In Response:

While the concentration of anesthetic in the fresh gas does indeed equal the vaporizer setting, once the fresh gas enters the anesthesia circuit, the fresh gas mixes with the existing volume of gases in the circle system. (Figure 1A) As a result, it takes time for any change in concentration of anesthetic vapor or other gases to come to a new equilibrium in the circuit and patient’s lungs. The time it takes to reach equilibrium depends primarily upon the total fresh gas flow and the internal volume of the circuit. The ratio of the internal volume to the fresh gas flow determines the time constant, which can be used to estimate how long it will take for a change in fresh gas flow concentrations to reach a new equilibrium in the circuit. For example, if the internal volume of the circuit is 5 L and the FGF is 5 L/min, the time constant is 1 minute. It takes four time constants to reach 98% of the new equilibrium. On the other hand, at 1 L/min FGF the time constant becomes 5 minutes, or 20 minutes to reach 98%. While high fresh gas flow can be used to change the concentration in the circuit more rapidly, the patient only absorbs a fraction of the oxygen and anesthetic in the fresh gas and all the excess ends up in the scavenging system as waste. Figures 1 A-C demonstrate the impact of FGF on the rate at which anesthetic concentrations change in the circuit.

Priming is a technique for increasing the anesthetic concentration in the circuit so that the anesthetic is more rapidly available when needed. It can be useful in the context of pediatric mask induction to speed the increase of inhaled anesthetic concentration. A detailed discussion of priming can be found in a recent article, but the following is a brief synopsis with some figures from the article. (See: Gordon, D. & Feldman, J. Environmentally Responsible Mask Induction. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 38, 321–331 (2024).

The ultimate example of priming is a single breath induction where a concentration of 8% sevoflurane is desired with the first breath. This can only be accomplished by turning on the fresh gas and vaporizer and ventilating the circuit into a reservoir bag to avoid room contamination. This process creates significant waste but does ensure a high concentration of anesthetic is immediately available at the y-piece.

Another approach to priming often used is to occlude the end of the circuit and turn on the vaporizer and fresh gas flow. This method does increase the anesthetic in the internal parts of the breathing circuit, but DOES NOT prime the inspiratory or expiratory limbs of the circuit. The occluded circuit holds both inspiratory and expiratory valves closed so no fresh gas can enter the circuit limbs. (Figure 2 A)

During pediatric mask induction, emptying the reservoir bag when the vaporizer is first turned on results in a partial priming, effectively reducing the internal volume of the circuit that does not contain anesthetic and shortens the time constant. This technique assists the induction process without creating excessive waste from a prolonged priming process. (Figure 2B)

FIGURES 1A-C

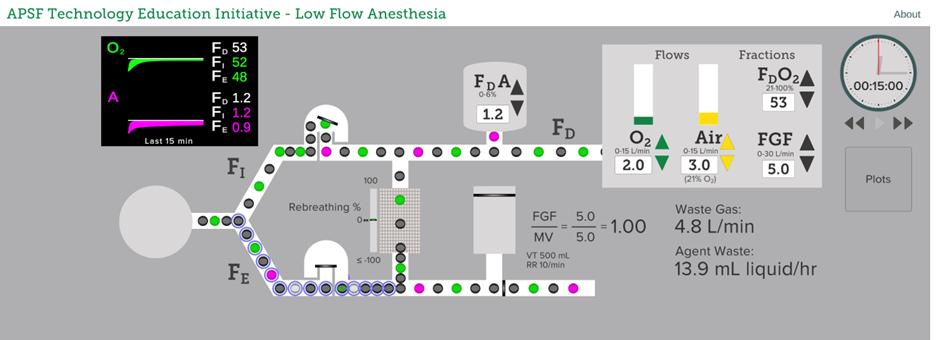

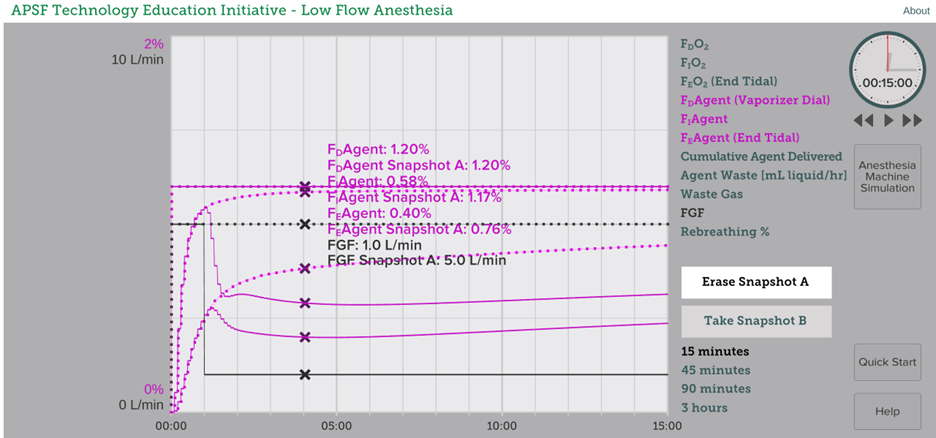

The APSF/ASA course on low flow anesthesia (apsf.org/tei/lfa) uses guided simulation to explore the relationship between fresh gas flow, gas concentrations in the circuit and waste that ends up in the scavenging system. While the figure is a static image of an idealized circle system, the simulation is animated and demonstrates how the concentrations change over time including uptake of anesthetic and oxygen. It is not possible to model the impact of priming with this tool, but the following example compares the change in anesthetic concentrations in the circuit at different fresh gas flows with a plot indicating the time required to reach equilibrium at different fresh gas flows.

Figure A - First 15 minutes of an anesthetic with FGF 5 L/min. Note that at this FGF there is no rebreathing of exhaled gas so the inspired concentrations of oxygen and anesthetic are the same as the delivered concentrations in the fresh gas.

Figure B – First 15 minutes with FGF reduced from 5 to 1 L/min after 1 minute. Inspired concentrations of oxygen and anesthetic are less than the concentrations delivered in the fresh gas due to rebreathing of exhaled gas.

Figure C – Comparative plots showing rate of change of inspired and expired anesthetic concentrations at two different fresh gas flows. Dotted lines 5 L/min, Solid lines 1 L/min. Note that inspired anesthetic concentration reaches 98% of the vaporizer setting after 4 minutes at 5 L/min. At 1 L/min the rise of inspired concentration is much slower due to longer time constant and rebreathing exhaled gas after uptake of oxygen and anesthetic vapor. Lower flows like 1 L/min can be used safely, but it is important to increase the vaporizer concentration well above the desired level to achieve adequate anesthesia in timely fashion.

FIGURES 2 A-B

Demonstration of priming taken from Gordon, D. & Feldman, J. Environmentally Responsible Mask Induction. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 38, 321–331 (2024).

Figure 2A – Example of priming with the circuit occluded. Note that the inspiratory and expiratory limbs are not primed and also the reservoir bag full of non-anesthetic containing gas is bypassed. This approach can help to speed the rate of rise of anesthetic during mask induction but also generates significant waste.

Figure 2B – Example of priming by emptying the reservoir bag just before applying the mask

Send your thoughts and comments to Myron (myasterster@gmail.com) who will post in a Friday reader response.

PS From Myron: Another way to think about Priming and time constants is to think about the half life of elimination (t1/2 beta) in basic pharmacology. When administering a drug it takes 3.3-5 half lives to achieve 90+% of steady state blood levels. Similarly it takes about 4 time constants (half lives) to achieve steady state gas concentrations in the circuit.