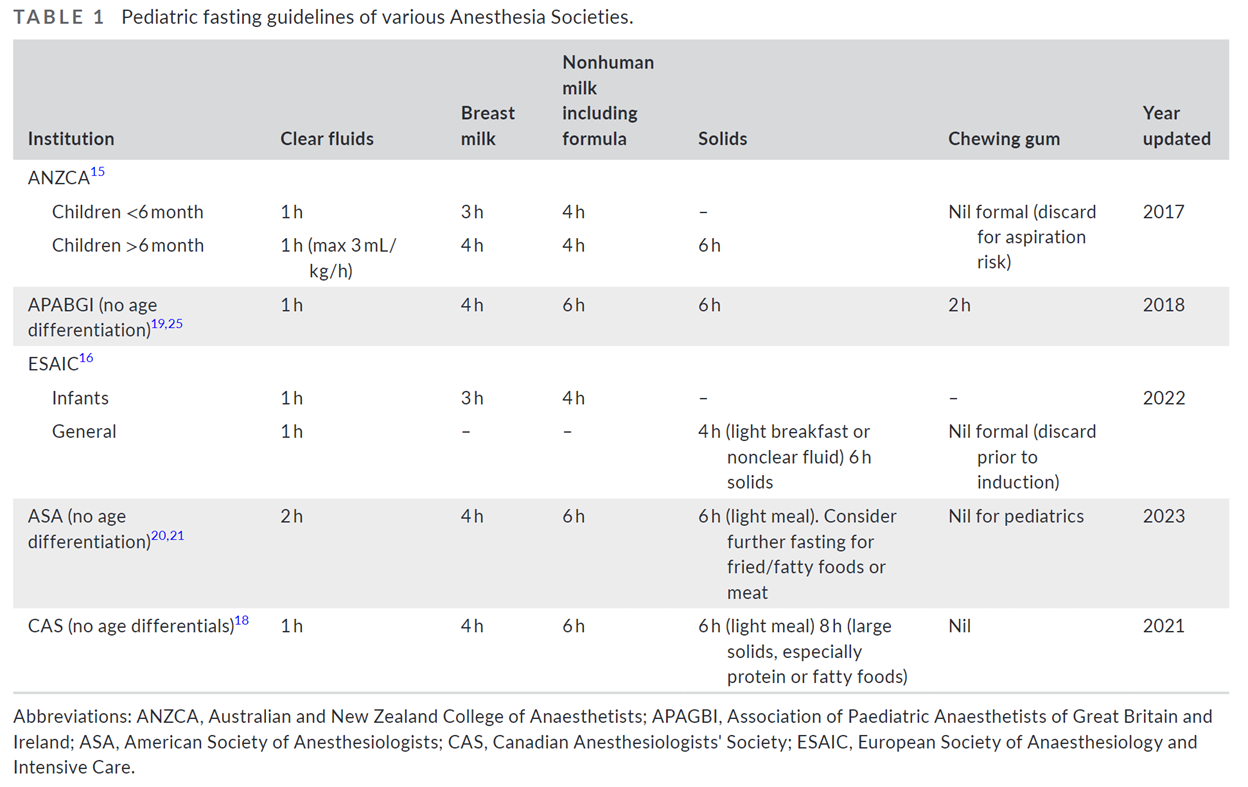

Over the past 2 years we’ve frequently discussed and reviewed several articles concerning pediatric preoperative fasting guidelines. Indeed, these previous PAADs have been amongst our most highly viewed and read. Today’s article by Zhang et al.1 does not really add much “new” to this literature but is a terrific and extremely well written review of this topic and is worthy of being in your teaching portfolios for new trainees or as a focus article for a journal club. Further, there is a really good table that I am including that beautifully summarizes the fasting guidelines of various Anesthesia Societies and may be invaluable to you if you are trying to change your institution’s fasting guidelines. Myron Yaster MD

Educational review

Zhang, E, Hauser, N, Sommerfield, A, Sommerfield, D, von Ungern-Sternberg, BS. A review of pediatric fasting guidelines and strategies to help children manage preoperative fasting. Pediatr Anesth. 2023; 33: 1012-1019. doi:10.1111/pan.14738

Pre-procedure fasting before general anesthesia and deep sedation is designed to reduce the volume, pH, and contents of residual gastric contents at the induction of general anesthesia. The goal is to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents when airway protective reflexes are obtunded or lost. Indeed, fasting, or “NPO after midnight”, may have been one of the first things most of us learned on an anesthesia rotation as students or at the beginning of our anesthesia residency training. But is it necessary?

“Pediatric fasting guidelines are typically divided into clear fluids, breast milk, formula, and solids. Clear fluids have been defined by the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) as “water, carbohydrate rich fluids, specifically developed for perioperative use, pulp free fruit juice, clear cordial, black tea and coffee … excludes fluids containing particulate matter, soluble fibre, milk-based drinks and jelly.”2 Internationally, solids have also been further divided into light breakfasts (specified as “buttered toast with jam or cereals with milk”) and solids (other foods not previously included)3.”1

“The pediatric fasting guidelines have recently been updated in multiple countries (Table) to reflect the latest evidence for gastric emptying, and the minimal morbidity and mortality data reflected in pediatric patients who do aspirate.”1 Why the desire to change the fasting times for clear liquids? After all, “if it ain’t broke, why fix it?” The primary reason is that many children are fasted excessively and arrive famished and on occasion even dehydrated. Parents informed to feed clears up to 2 hours before surgery often fast their children for far longer times.4 “This has both psycho-social and physiological consequences for the child, as well as being potentially distressing for both the child and parents.”1

Zhang et al. discuss 2 issues that we had not considered before reading the article. First, fasting results in the release of stress hormones which produce insulin resistance. This “increased free fatty acids (FFA), decreased FFA/ketone body ratios, decreased insulin levels, and increased cortisol levels”1, results in hyperglycemia. “Sato et al.5 demonstrated in the adult cardiac surgical patient, a well-studied cohort, that regardless of the presence of diabetes, there were increased major complications (death, cardiac failure, stroke, dialysis or severe infection) and minor infections for every 1 mg/kg/min reduction in insulin sensitivity.”1 The second issue concerned chewing gum. I must admit that I (MY) used to hate it when the preop nurses would tell me that my patient arrived chewing gum. I really didn’t care as long as the kid spit out the gum before coming to the OR. Zhang et al. point out that chewing gum increases satiety and reduces hunger in adults. It really doesn’t do much in terms of gastric fluid volume or pH. However, if chewing gum reduces hunger isn’t that a good thing in patients who are fasting!?

From many personal discussions and public responses to previous PAADs, it’s pretty clear to us that many institutions and practitioners have changed and reduced their clear liquids fasting guidelines from two to one hour. Indeed, some have changed their policies to encourage clear liquids when patients arrive to the preoperative staging area.

Zhang et al recommend “a good starting point to optimizing fasting times in children is the repeated education of staff and parents regarding the institutional limits, and the encouragement of fluids and a light breakfast where appropriate. Further, given the evidence for minimal harm with clear fluids up to 1 h [or 2 hours, following ASA guidelines] preoperatively, the provision of liberal fluids to decrease the sensation of hunger could be further considered.”1

Have you or have you not changed your practice? Send your thoughts to Myron who will post them in a Friday Reader response.

References

1. Zhang E, Hauser N, Sommerfield A, Sommerfield D, von Ungern-Sternberg BS: A review of pediatric fasting guidelines and strategies to help children manage preoperative fasting. Pediatric Anesthesia 2023; 33: 1012-1019

2. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA): Guideline on pre-anaesthesia consultation and patient preparation., 2017

3. Li L, Wang Z, Ying X, Tian J, Sun T, Yi K, Zhang P, Jing Z, Yang K: Preoperative carbohydrate loading for elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Today 2012; 42: 613-24

4. Singla K, Bala I, Jain D, Bharti N, Samujh R: Parents' perception and factors affecting compliance with preoperative fasting instructions in children undergoing day care surgery: A prospective observational study. Indian J Anaesth 2020; 64: 210-215

5. Sato H, Carvalho G, Sato T, Lattermann R, Matsukawa T, Schricker T: The association of preoperative glycemic control, intraoperative insulin sensitivity, and outcomes after cardiac surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95: 4338-44