Patient Blood Management: The role of tranexamic acid (TXA)

Myron Yaster MD, Jayant K. Deshpande, and Justin L. Lockman MD, MSEd

The September issue of Anesthesia and Analgesia is a themed issue (14 articles, yikes!) highlighting patient blood management (PBM). “What is PBM?”, you ask? According to the authors, “Patient blood management encompasses all aspects of optimizing a patient’s blood health. Blood is the body’s liquid organ. Responsible for oxygen delivery, blood has many functions, including maintaining the delicate balance between hemostasis and thrombosis. Suboptimal blood health can manifest as anemia, coagulopathy, hemostasis, bleeding, and/or thrombosis. PBM involves the timely, multidisciplinary application of evidence-based multimodal medical and surgical concepts aimed at screening for, diagnosing and appropriately treating anemia, minimizing surgical, procedural, iatrogenic blood losses, and managing coagulopathic bleeding to improve health outcomes through patient-centered care”.[1]

The PAAD coincidentally recently reviewed an article from Pediatric Critical Care Medicine on plasma and platelet transfusion (Sept 20, 2022) similar to one in this issue of A&A.[2, 3] Over the next few weeks, the PAAD team will review several of the articles from this PMB-themed A&A issue.

Today’s PAAD is an update on Tranexamic acid (TXA) as a method of reducing intraoperative blood loss, a topic that is very close to my heart. One of my very first published clinical research studies was a randomized-controlled, double blind study comparing nitroglycerine and nitroprusside to induce deliberate hypotension in children undergoing posterior spine surgery.[4] At the time, deliberate hypotension was a common blood conservation technique for big, bloody surgical procedures because it produced a relatively bloodless surgical field, facilitated surgical dissection, decreased intraoperative time, and significantly reduced blood loss. The technique fell out of favor when it, together with normovolemic hemodilution and the prone position, was associated with blindness upon awakening.

My study (and the deliberate hypotension technique) is little remembered today, but it provided me with a lasting memory and appreciation of just how difficult it was, and is, to accurately measure intraoperative blood loss. In that study, we had to weigh surgical sponges and drapes, measure suction cannister volumes, record all of the surgical irrigation fluids, etc. It made me realize just how inaccurate blood loss measures are – not just for research but in everyday anesthetic management. Indeed, to the day I retired I always laughed when asked by the surgical resident or intern, “What was the blood loss?” To me this is a multiple-choice question, with only three answers: “minimal,” “moderate,” or “I had to put on galoshes.” But that’s another story for another PAAD. Myron Yaster MD

Editorial Goobie SM. Patient Blood Management Is a New Standard of Care to Optimize Blood Health. Anesth Analg. 2022 Sep 1;135(3):443-446. PMID: 35977353

Original article

Patel PA, Wyrobek JA, Butwick AJ, Pivalizza EG, Hare GMT, Mazer CD, Goobie SM. Update on Applications and Limitations of Perioperative Tranexamic Acid. Anesth Analg. 2022 Sep 1;135(3):460-473. PMID: 35977357

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a synthetic lysine analog that inhibits the activation of plasminogen to plasmin and thereby inhibits the process of fibrinolysis (see this figure):

TXA is excreted in the urine largely unchanged, with filtration inversely proportional to plasma creatinine. TXA permeates all tissues, crossing the blood-brain barrier, synovial membranes, and the placenta. Its use and dosing regimens in cardiac surgery, obstetrics, acute trauma, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery and pediatric surgery are discussed extensively in today’s article. For purposes of this PAAD we will highlight author comments about TXA use in pediatric surgery.

“Prospective randomized-controlled trials have demonstrated that TXA use in children undergoing cardiac, craniosynostosis, and spinal fusion surgery is effective in reducing blood loss and transfusion. A blood loss reduction of 25% to 50% has been reported with TXA with a corresponding reduction in transfusion requirements. It is also recommended for other pediatric high/moderate blood loss scenarios such as neurosurgery, plastic and maxillary surgeries, organ transplantation, head and neck surgeries, major abdominal surgeries, and in those children with higher risk such as in the trauma setting.”[5] Despite this seemingly clear statement, there are many patients undergoing elective surgery in the above categories who do not routinely receive TXA in 2022. Should they? Would it be beneficial (in a clinically relevant way) for surgical patients to go home with higher hemoglobin values even if they were not going to going to receive any blood transfusions anyway? Would the financial cost of this added therapy be worth the benefits? Would large-scale TXA administration demonstrate an increased risk for thrombotic or other events that has not been seen in research studies thus far?

According to the authors, “Absolute contraindications for the pediatric patient include hypersensitivity, active thromboembolic disease, and fibrinolytic conditions with consumption coagulopathy. [Importantly, and different from adult studies,] TXA is not contraindicated in children with a seizure disorder.”[5]

“Using pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation, a dosing regimen of 10- to 30-mg/kg loading dose (maximum 2 grams) and 5- to 10-mg/kg/h maintenance infusion rate to maintain TXA plasma concentrations in the 20- to 70-mcg/mL range may be considered as a target for pediatric trauma and cardiac and noncardiac surgeries. TXA dosing in cardiac surgery has unique concerns taking into consideration the targeted plasma concentration, the patient’s age (with higher doses for neonates and infants [presumably due to volume of distribution]), and TXA added to [or diluted by] the cardiopulmonary bypass circuit prime.”[5]

It is also worth noting that the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) is currently studying the use of TXA with a multicenter trial in pediatric trauma. Perhaps those data will change recommendations in the coming years. But please let us know through your responses if you have thoughts about the questions posed above, or if your practice is different than what we’ve outlined. For example, is anyone using TXA for tonsillar bleeds?

A final thought: I (MY) couldn’t find TXA as a treatment option in SPA’s PediCrisis V 2 app under the massive hemorrhage event tab. I believe that recommended loading and maintenance TXA dosing schedules should be added to it ASAP. What do you think?

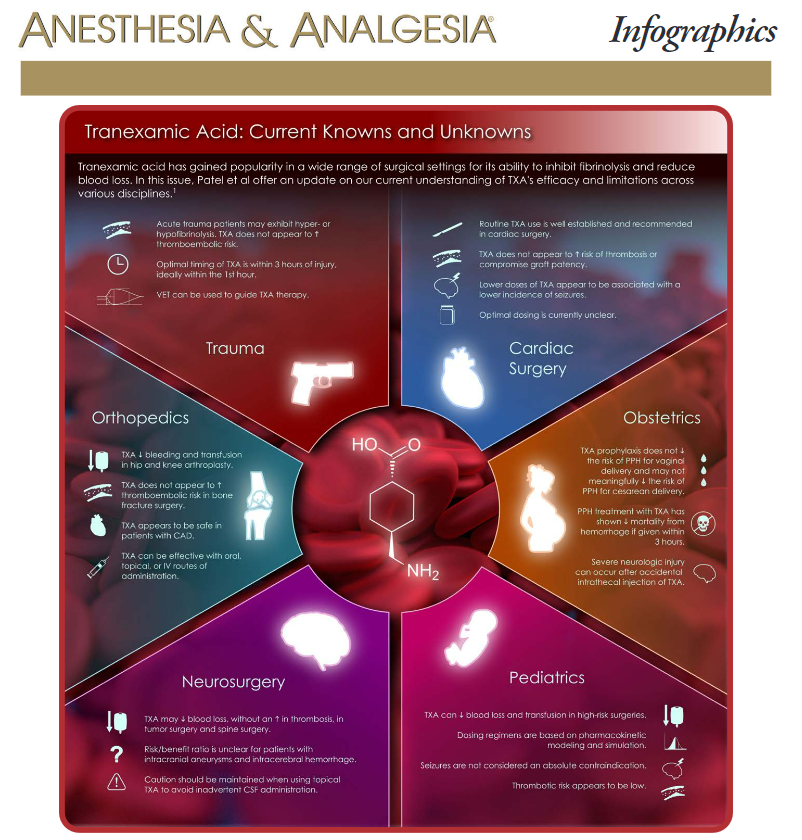

Infographic

Naveen Nathan. Tranexamic Acid: Current Knowns and Unknowns. Anesth Analg. 2022 Sep 1;135(3):459. PMID: 35977356

References

1. Goobie, S.M., Patient Blood Management Is a New Standard of Care to Optimize Blood Health. Anesth Analg, 2022. 135(3): p. 443-446.

2. Nellis, M.E., et al., Executive Summary of Recommendations and Expert Consensus for Plasma and Platelet Transfusion Practice in Critically Ill Children: From the Transfusion and Anemia EXpertise Initiative-Control/Avoidance of Bleeding (TAXI-CAB). Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2022. 23(1): p. 34-51.

3. Valentine, S.L., J.M. Cholette, and S.M. Goobie, Transfusion Strategies for Hemostatic Blood Products in Critically Ill Children: A Narrative Review and Update on Expert Consensus Guidelines. Anesth Analg, 2022. 135(3): p. 545-557.

4. Yaster, M., et al., A comparison of nitroglycerin and nitroprusside for inducing hypotension in children: a double-blind study. Anesthesiology, 1986. 65(2): p. 175-179.

5. Patel, P.A., et al., Update on Applications and Limitations of Perioperative Tranexamic Acid. Anesth Analg, 2022. 135(3): p. 460-473.