Today’s Pediatric Anesthesia Article of the Day is from the special lung and ventilation issue of the Journal Pediatric Anesthesia and it combines a pulmonary topic, one lung ventilation, with another recurrent set of articles in the journal - error traps in pediatric anesthesia practice. Again, as background, error traps can be defined as single or multiple circumstances that can result in an undesirable consequence such as an accident or complication. Common error traps include distractions/interruptions, first/late shifts, multiple tasks, overconfidence, the physical environment, time pressure, etc. There are many tools to address error traps such as STAR (Stop, Think, Act, Review) and Event-Free Check (Correct area, component and procedure, Hazard and condition review, Evaluate for error traps, Keep attention on task). Today’s article is not really about error traps, despite its title and format; rather, it describes common problems with one lung ventilation and how to prevent/solve them. I’ve included some of the treatment algorithms from the paper that I think many of you will find useful. Myron Yaster MD

Original article

Alina Lazar, Debnath Chatterjee, Thomas Wesley Templeton. Error traps in pediatric one-lung ventilation. Paediatr Anaesth. 2022 Feb;32(2):346-353. PMID: 34767676

“One-lung ventilation (OLV) is commonly used to facilitate surgical exposure for intrathoracic surgeries involving the lungs, pleura, vascular structures, esophagus, mediastinum, thoracic wall, and spine. Less commonly, anatomical lung isolation is also necessary to prevent soiling from the contralateral lung from pulmonary hemorrhage or empyema, or to allow differential ventilation. The popularity of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) in children has increased the demand for OLV.”(1,2) Depending on age and patient size there are essentially 3 commonly use methods to achieve OLV, endobronchial intubation with a cuffed (or uncuffed) tracheal tube, bronchial blockers, and double lumen tubes. I (MY) have to admit that I can never remember bronchial blocker and double lumen tube sizes and finding them on line or in a textbook is often an exercise in frustration. The authors provided this terrific schematic decision tree diagram which provides this information and we think should be reproduced and placed on your anesthesia work stations.

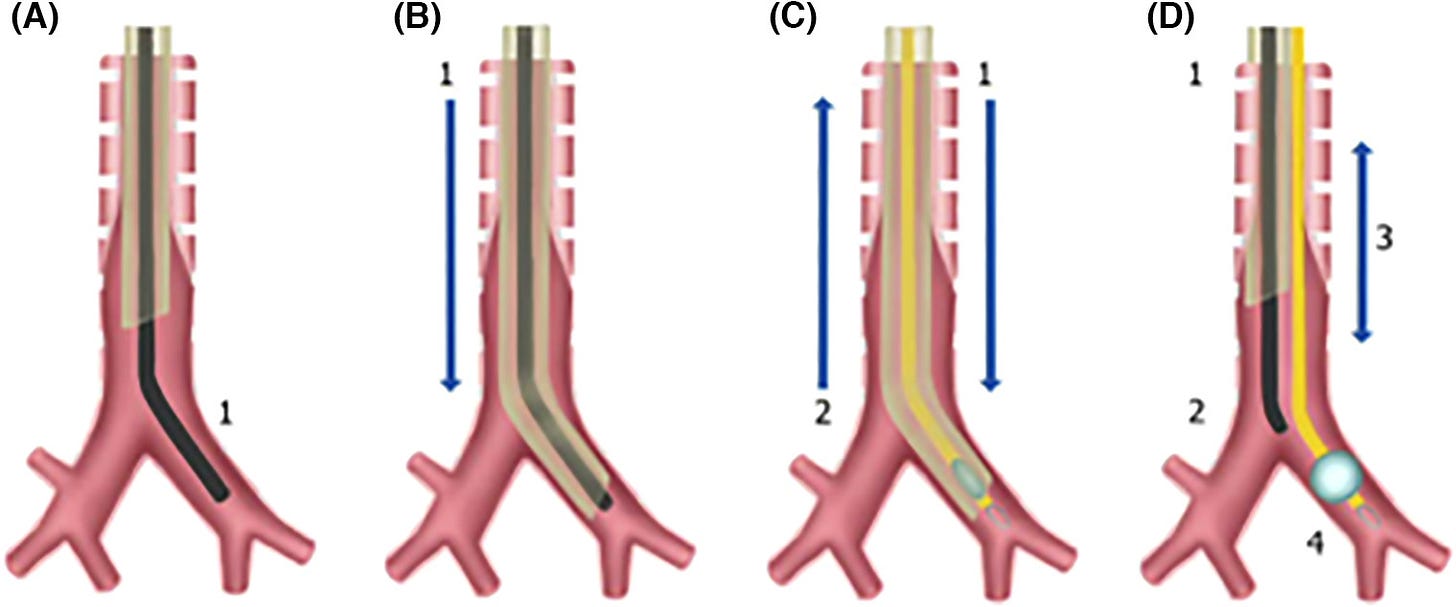

Another common problem in OLV is how to place a bronchial blocker.(3) Should it be intra-or extra-luminal with respect to the endotracheal tube? What’s the best way to place these blockers and insure/confirm proper positioning for lung isolation? Again the authors provide a terrific figure to help. In addition, they provide problem solving strategies and solutions to the loss of lung isolation during surgery.

Finally, the authors provide solutions to very common problems with OLV, namely how to ventilate the patient and how to treat intraoperative hypoxemia. They provide clear guidance on ventilatory parameters and another great figure - a treatment algorithm for hypoxemia. They suggest using 4-7 mL/kg tidal volumes, 4 cm PEEP, and peak inspiratory pressures ranging between 21-24 cm pressure. Finally, they recommend permissive hypercapnia, a topic that we will address in a forthcoming PAAD.

Myron Yaster MD and Lynne Maxwell MD

References

1. Lazar A, Chatterjee D, Templeton TW. Error traps in pediatric one-lung ventilation. Paediatr Anaesth 2022;32:346-53.

2. Templeton TW, Piccioni F, Chatterjee D. An Update on One-Lung Ventilation in Children. Anesth Analg 2021;132:1389-99.

3. Hammer GB. Single-lung ventilation in infants and children. Paediatr Anaesth 2004;14:98-102.