More on Video versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Urgent Intubation of Newborn Infants

Myron Yaster MD, Jamie Peyton MD, and Melissa Brooks Peterson MD

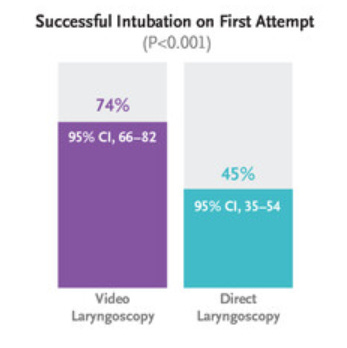

In today’s PAAD, Geraghty et al.1 once again demonstrate in a single center study that “among neonates undergoing urgent endotracheal intubation in the delivery room or NICU, video laryngoscopy resulted in a greater number of successful intubations on the first attempt than direct laryngoscopy.” Over the past year we’ve reviewed several similar papers in the PAAD with similar results.2,3

Original article

Geraghty LE, Dunne EA, Ní Chathasaigh CM, Vellinga A, Adams NC, O'Currain EM, McCarthy LK, O'Donnell CPF. Video versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Urgent Intubation of Newborn Infants. N Engl J Med. 2024 May 30;390(20):1885-1894. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2402785. Epub 2024 May 5. PMID: 38709215.

https://www-nejm-org.proxy.hsl.ucdenver.edu/doi/full/10.1056%2FNEJMoa2402785

In this prospective randomized controlled trial, “data were analyzed for 214 of the 226 neonates who were enrolled in the trial, 63 (29%) of whom were intubated in the delivery room and 151 (71%) in the NICU. Successful intubation on the first attempt occurred in 79 of the 107 patients (74%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 66 to 82) in the video-laryngoscopy group and in 48 of the 107 patients (45%; 95% CI, 35 to 54) in the direct-laryngoscopy group (P<0.001). The median number of attempts to achieve successful intubation was 1 (95% CI, 1 to 1) in the video-laryngoscopy group and 2 (95% CI, 1 to 2) in the direct-laryngoscopy group. The median lowest oxygen saturation during intubation was 74% (95% CI, 65 to 78) in the video-laryngoscopy group and 68% (95% CI, 62 to 74) in the direct-laryngoscopy group; the lowest heart rate was 153 beats per minute (95% CI, 148 to 158) and 148 (95% CI, 140 to 156), respectively.”1

Some key features:

1. The video laryngoscope used in the study was a C-MAC, Karl Storz with size/age-appropriate Miller straight blades. Hyper angulated blades were not used.

2. The clinician INTUBATORS were pediatric residents and neonatal fellows, with an attending neonatologist as the back-up if the trainees failed.

3. Medication to facilitate intubation in the NICU (NOT in the Delivery Room) included: intravenous fentanyl (2 mcg/kg), atropine (20 mcg/kg), and succinylcholine (2 mg/kg)

4. Supplemental Oxygen WAS NOT GIVEN DURING during the intubation attempts.

5. Uncuffed endotracheal tubes were used.

Ok what does this mean? Your first attempt should be your best attempt. And once again, as in the pediatric anesthesia difficult airway studies,4,5 videolaryngoscopy especially with straight, non-hyperangulated is superior compared to standard direct laryngoscopy. Further, the major negative consequence that occurred to patients in this study was hypoxemia during the intubation attempts. Again, as discussed previously, this highlights the need to provide supplemental oxygen during ALL of your intubations, particularly in neonates and small infants. We hope we have demonstrated to you over the last year of airway-focused PAADs that you should utilize supplemental passive oxygenation during laryngoscopy and intubation, and if you aren’t, it’s time to change.

Finally, one of the most intriguing aspects of this study was how patients were randomized. Clearly, in the urgent settings of this study, prior consent would be almost impossible. How did they do it? “We sought prospective written informed consent from the parents of the infants for inclusion in the trial when possible (e.g., when extremely preterm birth was anticipated or in neonates with anomalies likely to result in intubation, such as diaphragmatic hernia). Given that many neonates are urgently intubated with little advance warning, that both direct laryngoscopy and video laryngoscopy were used at National Maternity Hospital and the School of Medicine, Dublin Ireland, and that trial inclusion did not pose an additional burden to neonates or families, our ethics committee approved a deferred consent process. In circumstances in which there was insufficient time to approach parents beforehand, the type of laryngoscope used was randomly assigned, data were collected, and written informed consent was sought from parents to use the data as soon as was practical.”1 Having been involved in many clinical trials in the U.S, we are not sure if our IRBs would have agreed to this. Would yours?

JP and MBP have a few thoughts that we’d like to share. We were pleased, surprised, and frustrated all at the same time. We were pleased to see that our own personal bias and clinical practice patterns have been confirmed again (it’s always good not to be forced to change your mind!) and that one of the biggest journals in the world was interested enough to publish this study. We were surprised that a journal as prominent as the New England J of Medicine would publish a single-center study that did not add anything new to our existing knowledge base. Finally, we were surprised that once again prominent papers examining airway management are still focusing on ‘VL vs DL’. For any new readers of the PAAD, we will once again point out that VL and DL are not mutually exclusive techniques and should not be thought of in opposition. The skills to perform direct laryngoscopy, video-assisted direct laryngoscopy, and indirect video laryngoscopy are all vital for anyone managing an airway. Video-enabled laryngoscopes, whether to perform direct or indirect laryngoscopy, must now be considered vital tools in any environment where tracheal intubation may take place. This study confirms what is already known about laryngoscopy in neonates and infants and, as such, can be absorbed into the existing knowledge base. But this study does not move us any further forward in our quest to improve patient safety in this high-risk group. Research into airway management must move on from examining the equipment we use and take a broader view. For example, we need to ask how we teach and maintain skills? What systems do we have in place to prepare inexperienced clinicians when they are learning how to perform intubation? Can we minimize the cognitive loads placed on those performing high-risk procedures, particularly those learning or those who rarely perform the procedure? Do we need bundles of care where each individual part has been shown to bring an incremental improvement in safety, hopefully leading to greater overall improvements? We would suggest that the first bundle of care should implement supplemental passive oxygenation regardless of the type of airway device being employed to secure the airway. How do we implement bundles of care and change practice within a hospital, region, or nationally? The focus needs to move away from which device we should use, to how we use them as part of an overarching airway management strategy that places patient safety at the centre.

Are you finally convinced to switch to video laryngoscopy with a C MAC and supplemental oxygen on your first attempt? Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

1. Geraghty LE, Dunne EA, CM NC, et al. Video versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Urgent Intubation of Newborn Infants. The New England journal of medicine 2024;390(20):1885-1894. (In eng). DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2402785.

2. Lingappan K, Neveln N, Arnold JL, Fernandes CJ, Pammi M. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation in neonates. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2023;5(5):Cd009975. (In eng). DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009975.pub4.

3. Ruetzler K, Bustamante S, Schmidt MT, et al. Video Laryngoscopy vs Direct Laryngoscopy for Endotracheal Intubation in the Operating Room: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2024;331(15):1279-1286. (In eng). DOI: 10.1001/jama.2024.0762.

4. Peyton J, Park R, Staffa SJ, et al. A comparison of videolaryngoscopy using standard blades or non-standard blades in children in the Paediatric Difficult Intubation Registry. British journal of anaesthesia 2021;126(1):331-339. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.08.010.

5. Gálvez JA, Acquah S, Ahumada L, et al. Hypoxemia, Bradycardia, and Multiple Laryngoscopy Attempts during Anesthetic Induction in Infants: A Single-center, Retrospective Study. Anesthesiology 2019;131(4):830-839. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/aln.0000000000002847.