Monitoring pediatric opioid induced respiratory depression

Myron Yaster MD and Lynne G. Maxwell MD

I’ve got to admit that I’ve been interested in the issue of monitoring for impending respiratory depression in pediatric patients for a long time. When my colleagues and I started the pediatric pain service at Johns Hopkins in 1989, we didn’t know how, or even whether, we could safely administer opioids to pediatric patients, particularly those less than 5 years of age. Could PCA be used? And in what age group? Could nurses or parents initiate a demand dose? Were background basal infusions safe? Additionally, there were many other non-pain service patients at increased risk of respiratory depression who also needed respiratory monitoring such as the very young (less than 60+ weeks post-conceptual age) following general anesthesia and surgery, patients with sleep disordered breathing, patients receiving opioids either alone or combined with sedative hypnotics, etc.

Today’s PAAD by Vecchione and Monitto1 is an outstanding review of monitoring for opioid-induced respiratory depression from the June issue of the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. It’s a concise and beautifully written article that I would urge you to download and read in its entirety. We’ve covered this topic in several previous PAADs. Many of you are new to the PAAD community and others are old hands who might find these useful to revisit. I am reposting some of them for your review. Myron Yaster MD

PAAD 05/23/2024 Universal in-hospital respiratory depression monitoring after surgery https://ronlitman.substack.com/p/universal-in-hospital-respiratory

PAAD 02/08/2022 A non-invasive respiratory volume monitor https://ronlitman.substack.com/p/a-non-invasive-respiratory-volume

PAAD 10/04/2021 Fentanyl and Respiratory Depression https://ronlitman.substack.com/p/fentanyl-and-respiratory-depression

Original article

Vecchione T, Monitto C. Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression—Pediatric Considerations. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. 06/20241

Opioids are the essential building block in the management of moderate to severe pain. Regardless of the method of administration, all opioids produce unwanted side effects such as nausea and vomiting, constipation, pruritus, urinary retention, cognitive impairment, tolerance, physical dependence, and, on occasion, respiratory depression. Although there are several causes of postoperative respiratory depression in the pediatric patient population, like obstructive sleep apnea, very young age, and neuromuscular disease, opioid administration is one of the most common and feared. The Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation has developed specific recommendations for patient respiratory monitoring in adult patients which have been extrapolated to pediatric patients.2 Unfortunately, monitors that are well tolerated in adults may not work well in children.3

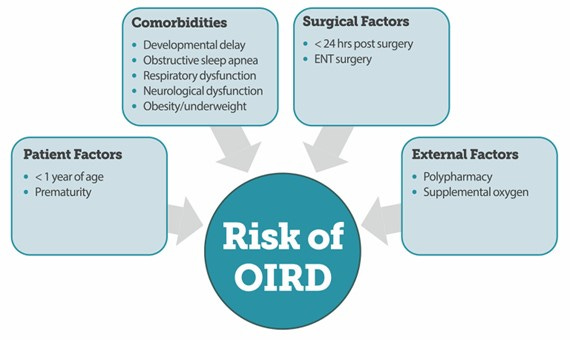

The risk factors for opioid-induced respiratory depression are summarized in the following figure:

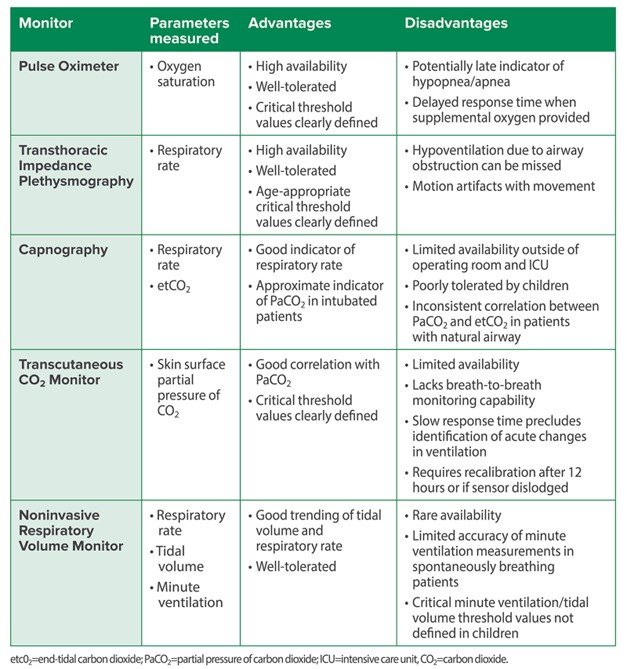

The guts of today’s PAAD by Vecchione and Monitto answers the question: How should we monitor pediatric patients at risk for opioid-induced respiratory depression? A wonderful summary from the article breaks down the advantages and disadvantages of the many types of monitors available to you. The most common monitor is the pulse oximeter. As we discussed in a previous PAAD, the use of supplemental oxygen may4 or may not5 delay the detection of hypoxemia. Another common technique, transthoracic impedance plethysmography, monitors respiratory rate and is a technique that can identify apnea and hypopnea, hallmarks of opioid effects on brainstem respiratory centers. It is commonly available, well tolerated, and is the monitor most of you use in the PACU and many hospital and procedure units. Unfortunately, it will not detect respiratory depression from an obstructed airway, indeed, it may show a high respiratory rate associated with continued chest wall motion in the setting of airway obstruction and decreased air entry. Capnography (end-tidal CO2) is the gold standard in the adult patient population and is recommended by the APSF. However, it is poorly tolerated in pediatric patients who often simply remove the device.3 Newer devices that non-invasively measure tidal volume and respiratory rate are well tolerated but haven’t achieved widespread acceptance.6,7 Although “transcutaneous CO2 monitoring fell out of favor in the 1980s in part due to technical challenges, including the risk of skin burns when used on neonates, as a result of technological advances, transcutaneous CO2 (TCO2) monitoring is now clinically feasible and safe. These monitors have been evaluated in pediatric populations” including neonates8 “but they have not been studied in infants and children receiving opioid medications in the postoperative setting. While correlation is good with steady state PaCO2, response time precludes rapid identification of acute changes in ventilation, limiting its utility as an early warning monitor.” Recent studies have demonstrated comparability between TCO2 and PaCO2 in neonates8 as well as better correlation of TCO2 than ETCO2 with PvCO2 in neonates and infants under 10kg undergoing surgery with general anesthesia.9 These findings may warrant evaluation of these technologically more advanced monitors in the postoperative setting in patients receiving opioids.

The authors conclude; “no models designed to predict the risk of opioid-induced respiratory decompensation in children currently exist. When stratifying risk, patient-specific factors unique to children should be included as opposed to extrapolating results from adult studies. Continuous electronic respiratory monitoring of children is reported to be more commonly utilized than in the care of adults, but no single technology provides a comprehensive solution for monitoring those with a natural airway. In the future, the use of multiple, complementary monitors in conjunction with paradigms designed to include pediatric-specific threshold alarm parameters may allow for earlier identification of episodes of respiratory insufficiency in this vulnerable population.”1

What are using in your practice? Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

1. Vecchione T, Monitto C. Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression—Pediatric Considerations. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. 06/2024 (https://www.apsf.org/article/opioid-induced-respiratory-depression-pediatric-considerations/?utm_source=APSF+Newsletter+Email+-+External&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2024_06_01).

2. Weinger MB, Lee LA. No patient shall be harmed by opioid-induced respiratory depression. APsF Newsletter 2011;26(2):21.

3. Miller KM, Kim AY, Yaster M, et al. Long-term tolerability of capnography and respiratory inductance plethysmography for respiratory monitoring in pediatric patients treated with patient-controlled analgesia. Paediatric anaesthesia 2015;25(10):1054-9. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/pan.12702.

4. Cravero JP, Agarwal R, Berde C, et al. The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia recommendations for the use of opioids in children during the perioperative period. Paediatric anaesthesia 2019;29(6):547-571. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/pan.13639.

5. Taenzer AH, Perreard IM, MacKenzie T, McGrath SP. Characteristics of Desaturation and Respiratory Rate in Postoperative Patients Breathing Room Air Versus Supplemental Oxygen: Are They Different? Anesthesia and analgesia 2018;126(3):826-832. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000002765.

6. Atkinson DB, Sens BA, Bernier RS, Gomez-Morad AD, Imsirovic J, Nasr VG. The Evaluation of a Noninvasive Respiratory Volume Monitor in Mechanically Ventilated Neonates and Infants. Anesthesia and analgesia 2022;134(1):141-148. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000005562.

7. Gatti S, Rezoagli E, Madotto F, Foti G, Bellani G. A non-invasive continuous and real-time volumetric monitoring in spontaneous breathing subjects based on bioimpedance-ExSpiron®Xi: a validation study in healthy volunteers. Journal of clinical monitoring and computing 2024;38(2):539-551. (In eng). DOI: 10.1007/s10877-023-01107-0.

8. Baumann P, Gotta V, Adzikah S, Bernet V. Accuracy of a Novel Transcutaneous PCO2 and PO2 Sensor with Optical PO2 Measurement in Neonatal Intensive Care: A Single-Centre Prospective Clinical Trial. Neonatology. 2022;119(2):230-237. doi: 10.1159/000521809. Epub 2022 Feb 4. PMID: 35124680.

9. Chandrakantan A, Jasiewicz R, Reinsel RA, Khmara K, Mintzer J, DeCristofaro JD, Jacob Z, Seidman P. Transcutaneous CO2 versus end-tidal CO2 in neonates and infants undergoing surgery: a prospective study. Med Devices (Auckl). 2019 May 6;12:165-172. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S198707. PMID: 31191045; PMCID: PMC6515535.