Good morning and welcome back to another episode of medicolegal Monday. Today we’ll discuss (yet another) tragic case, this one involving a common medication error in the OR, and emphasize the importance of communication skills when complications occur. As in the past, this PAAD will be a little longer than usual, but I think the topic is so important that it will be worth the extra few minutes of reading time. For those interested, the references are listed below.

In the year 2001, as I was preparing to relocate from Rochester, NY to Philadelphia, I was asked by a small community hospital in upstate New York to help them investigate the death of a young boy undergoing a routine anesthetic. The case hadn’t yet reached the lawsuit phase, but it certainly looked like it would.

Justin Micalizzi was a healthy 11-year-old boy who underwent an ankle abscess incision and drainage. Out of nowhere, in the middle of the case, he became severely hypertensive and developed ventricular tachycardia, then fibrillation. All efforts to resuscitate him were unsuccessful and he died the following day after transfer to a tertiary care hospital. There wasn’t much on the anesthesia record to give me a clue as to what happened. He was ASA 1, and received a perfectly normal anesthetic that any of us would routinely administer. Propofol, sevoflurane, ondansetron. His vital signs were stellar until the moment of crisis. So, what happened? I murmured some vague thoughts about familial arrhythmias, but I, along with another consultant in pediatric critical care, found nothing that could explain the event. Until ten years later.

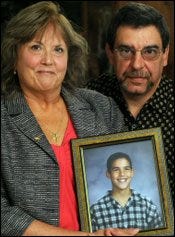

During those ten years, by complete coincidence, I met Justin’s parents, Dale and Gary Micalizzi. After Justin’s death, Dale had poured her energy and passion into becoming a patient safety advocate (read her story here), and had joined the Advisory Board of MHAUS. When I read her story, I easily recalled the case, and contacted her and told her about my role in the investigation. Dale and Gary told me about how painful it was to try to extract accurate information from the hospital about what happened to Justin. Her words:

“The immediate silence from the physicians, nurses, and the hospital’s chief executive officer was deafening. I recognized the classic pattern of denial and defense. I never wanted lawyers involved. I never wanted to question a physician’s judgment or a hospital’s care. There was no other option available to us. Mediators, ombudsmen, patient safety officers, and patient advocates were not yet invented. After three years of exhausting and frustrating attempts at an explanation, I sat in a law firm opposite attorneys representing Justin’s orthopedic surgeon and anesthesiologist.

“Almost no one wants to sue their doctors, especially following the death of a child. We love docs for caring for our children. But the stonewalling and the lack of responsibility and accountability that can occur after a complication infuriates patients and families. They want answers and a discussion even if nothing was intentionally or accidentally done wrong. Patients and families feel that the medical community owes them this. When they don't receive it, their own community pushes them into doing something, and litigation is the last straw. When a patient or family has been injured, and they sense this lack of disclosure, the priority shifts to preventing it from happening to someone else. The guilt that occurs by not acting to prevent injury or death to someone else is difficult to live with. We know what that pain feels like.”

Finally, in 2010, we found out what happened to Justin. Dale and I separately received calls from an anesthesiologist at the hospital where the incident occurred. They knew what happened, right from the beginning. Upon reaching into the drug tray for the vial of ondansetron, Justin’s anesthesia provider pulled out concentrated phenylephrine instead. The 1-mL vials look very similar and were located near each other in the tray. Ondansetron does not need to be diluted out of the vial, but phenylephrine requires a 100-fold dilution before administration. In the course of this accidental vial swap, Justin received a 100-fold (adult) overdose of phenylephrine.

In future PAADs, we will discuss how to prevent medication errors in the OR, and how to treat phenylephrine-induced severe hypertension. But today, I want to emphasize proper communication to families when complications occur.

It turns out, there’s a fair amount of scholarship in this area. Gerald Hickson, and his team at the Vanderbilt Center for Patient and Professional Advocacy have been studying the basis for physician complaints and lawsuits for decades. They’ve found that physicians can be classified into different risk groups. The highest risk group accounts for more than 50% of all malpractice claims. Do these high-risk physicians lack clinical skills? No. Do they have more complicated patients? Again, no. What they lack, is communication skills.

In survey after survey, malpractice actions largely come about for the same reasons: patients are unhappy with their interpersonal relationship with their physician; they perceive that information is being withheld; they see TV ads by personal injury law firms; they get advice to sue from healthcare workers; or they are under financial constraint.

On the other hand, patients do not sue when their physician is perceived as communicative; caring; honest; and apologetic.

Low-risk physicians, those that are hardly ever sued, have consistent characteristics. They: provide immediate unbiased investigation with complete disclosure; listen, tell the truth, and don’t protect the family; change practice to prevent similar events; put someone in charge; provide respect, empathy, apology, justice; and dismiss medical bills.

What risk type will you be?

I hope you all have a great start to the week, and, as before,

“Let’s be careful out there!” Sgt. Phil Esterhaus, Hill Street Blues

References:

Sloan FA: JAMA 1989; 262: 3291-7

Hickson GB: JAMA 1994; 272: 1583-7

Entman SS: JAMA 1994; 272: 1588-91

Hickson GB: N.C.Med.J. 2007; 68: 362-4

Vincent C:. Lancet 1994; 343: 1609-13

Hickson GB: JAMA 1992; 267: 1359-63

Huycke: Ann Intern Med 1994; 120: 792-8

Duclos: Int.J Qual.Health Care 2005; 17: 479-86

Levinson: JAMA 1997; 277: 553-9

Iedema: Sociol Health Illn 2009; 31: 262

Moore: Vanderbilt Law Review 2006; 59: 1175

Our systems should be built for the “ pilot” having their worse day and their best day. There are several systems solutions to this error but unfortunately many centers haven’t implemented them. The mantra in medicine is try harder read the label etc those things are important but given the inherent cognitive imperfections of the human brain will never be reliable solutions. Thanks for sharing Ron

Ron,

Good case discussion, at first I was concerned about identifying the patient, but I see that with Mom's advocacy, I'm sure you have her blessing. Most institutions but not all have taken steps to avoid errors like the one you describe. Rearranging the drug layout is one. I am also a strong advocate for some automated bar-coding/drug labeling system in the OR. There are several on the market and it allows the organization to kill two birds, labeling requirements and decreasing drug swap risk, with one stone.

I would like to encourage you in your position with ISMP to encourage the pharmaceutical industry to decrease with look alike drugs and drug concentrations that have to be altered prior to use.

Al