Over the past 2 days, Dr, David Jobes and I have reviewed an original review article by Crochemore et al.1 on early goal directed hemostatic therapy for severe acute bleeding management in the adult ICU. I approached reviewing this article with more than a bit of apprehension. I suspect that like many of you, the coagulation cascade is more the fuel of test taking nightmares than a pathway guiding therapeutic decision making. Obviously, this is not an area of my expertise, so I needed an expert to help with these PAADs.

Dr. Jobes was the obvious answer. I first met him when as a visiting medical student at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in 1976, I observed Dr. Jobes and his fellow, Dr. Charlie Cote, drawing lines on a young cardiac patient’s neck and placing one of the first pediatric internal jugular venous central lines using the Seldinger wire technique.2 I had never seen the Seldinger wire technique before and was awe struck. As they were placing the line, the cardiac surgeon entered the room and asked “what are you guys doing?” When informed that they were placing a central line, the surgeon was upset and told them to stop, he would do it either by cut down or by placing and RA catheter intraoperatively. Dr. Jobes very calmly told the surgeon “to go outside, smoke a cigarette and come back in 15 minutes, and we’ll have the line placed.” Much to my astonishment, the surgeon did what Dr. Jobes told him to do and the procedure was successful. It was the first time I had ever seen an anesthesiologist speak English, tell a surgeon to take a hike, and the surgeon listened. I think that was the moment that I wanted to become an anesthesiologist! Myron Yaster MD

Original review article

Crochemore T, Görlinger K, Lance MD. Early Goal-Directed Hemostatic Therapy for Severe Acute Bleeding Management in the Intensive Care Unit: A Narrative Review. Anesth Analg. 2024 Mar 1;138(3):499-513. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006756. Epub 2024 Feb 16. PMID: 37977195; PMCID: PMC10852045.

In their paper, Crochemore et al. integrate the current understanding of coagulation and hemostasis, therapies that are effective in controlling bleeding, and laboratory testing that guides those therapies. The recommendations are supported by numerous references of efficacy of both testing and therapies.

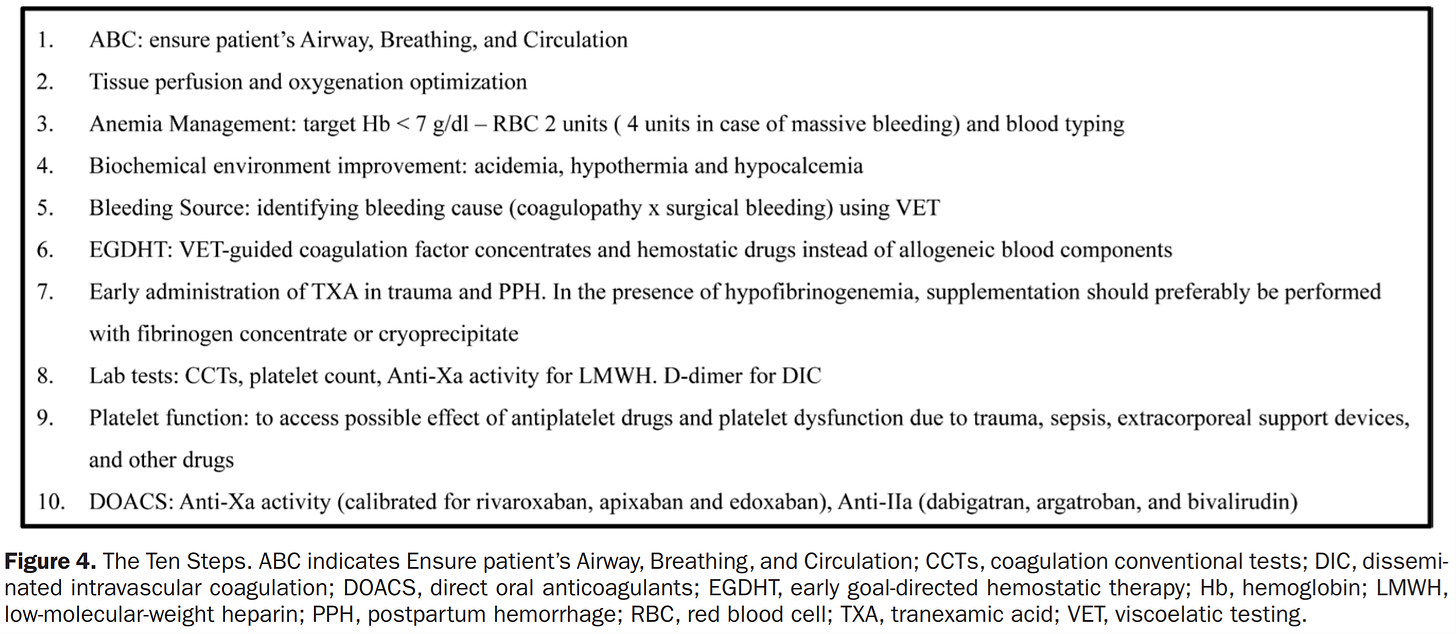

The authors propose a ten-step approach (figure) to bleeding to which I would add the following. Clinicians must replace lost blood continuously to sustain adequate perfusion and cannot wait for a laboratory test result to direct treatment. In those instances, and as a beginning in severe loss the use of fresh whole blood would be optimal (and possibly therapeutic In some cases). Eight of the steps include blood tests. The core is viscoelastic testing that has been refined since its introduction in 1948. The refinements have progressively increased the sensitivity and specificity of which elements of the coagulation system are the targets for therapy. Coupled with evolving therapeutics the authors provide a road map that is logical and highly likely to be effective. As a practicing cardiac anesthesiologist with a particular interest in the subject matter I applaud the authors for their work and A&A for publishing the paper for the anesthesia and critical care readers of the journal. What do we do next? The references separately demonstrate efficacy of tests and therapies, so the next step is to create a research protocol to determine the efficacy of the integrated whole (apply the ten steps in prospectively selective controlled group of patients). Assuming a positive result prospective data from the broad clinical application to demonstrate effectiveness as the last step to establish a standard practice. This idealistic approach to create evidence based best practice would take years and research funding to accomplish. Perhaps the medical community would be satisfied the evidence presented in the paper is sufficiently convincing to immediately begin to adopt the ten steps? How would that be accomplished?

In any scenario the ten steps must find its way into the hospital environment and that will require resources. The most significant resource is the testing which is referred to in 8 of the ten steps. What about testing? Starting in 1974 I learned how to personally test for heparin effect in the operating room as a cardiac anesthesiologist. Over many years when companies introduced point of care tests directly to clinicians (eg Hemochron, platelet count and function, TEG, etc) I incorporated them in the cardiac operating room to sort out bleeding issues. I eventually combined them with the intention to apply to any bleeding issues in the OR complex (similar to the ICU ten step proposal). I presented my idea to the medical director of the operating room and the director of the clinical laboratory. That was when I learned the following.

There are political and economic issues (in the USA different elsewhere). We, the clinicians, are not able to independently purchase, assign, and direct personnel to utilize the testing elements. All tests are the domain of the clinical laboratory whether in the laboratory environment or at point of care. It is responsible for overseeing virtually all the proposed testing for quality. In this respect the laboratory Is subject to regulatory review upon which state licensure (in USA) depends. Many of the tests can only be done in a laboratory environment, conducted by specifically trained technicians. Test equipment (whether in a laboratory or point of care) requires physical space, quality control, maintenance, reagents, certified operators, etc. The availability of testing and trained personnel will be necessary 24 hrs a day for bleeding patients (advances in technology will compensate for many of these issues). Not only available but quickly and repeatedly reported, also documented in the medical record and billed for patient charges/insurance. All these elements are costly. The laboratory operates on a budget approved by the hospital. There will be consideration of revenue generation vs expense. (My original ideas were not supported by the OR and Clinical Lab director based on budget/oversite considerations).

The readers would have benefitted from an accompanying economic model for consideration because it will be essential when you ask the director of the clinical laboratory to support 8 of the ten steps. Begin by inviting the director of the clinical lab to attend ICU grand rounds at which this paper would be presented/discussed. Or if the director is your friend make the proposition at lunch? Better yet along with the lab director convince the CEO of the hospital to insist on adopting the ten steps and produce the resources to make it happen – a fast track approach!

What do you think? Have you encountered similar road blocks? Have you overcome them? Send your comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

PS from Myron: On my recent volunteer mission in Israel, I learned that the Israel Defense Forces are having great success treating all of their battlefield injuries with fresh whole blood (and TXA) rather than component therapy. As discussed in several previous, PAADs I’ve often wondered why we don’t do this routinely in our ORs as well. As Dr. Jobes points out, the use of whole blood is optimal and possibly therapeutic. Isn’t it time for us to overcome the political and economic issues that prevent this as well as having the ability to use advanced laboratory testing to guide therapy?

References

1. Crochemore T, Görlinger K, Lance MD. Early Goal-Directed Hemostatic Therapy for Severe Acute Bleeding Management in the Intensive Care Unit: A Narrative Review. Anesthesia and analgesia 2024;138(3):499-513. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000006756.

2. Coté CJ, Jobes DR, Schwartz AJ, Ellison N. Two approaches to cannulation of a child's internal jugular vein. Anesthesiology 1979;50(4):371-3. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/00000542-197904000-00021.