Goal directed hemostatic therapy for severe bleeding part two

Myron Yaster MD and David Jobes MD

In yesterday’s PAAD we provided the framework of Crochemore et al.1 goal directed hemostatic therapy for severe bleeding using ViscoElastic Testing (VET). In today’s PAAD we will review their the concept of “The Ten Steps” for severe acute bleeding management, including an early goal-directed hemostatic therapy (EGDHT) algorithm to support clinicians in decision-making.

Recall that Crochemore et al.1 proposed “a functional classification of coagulation based on the physiology in 3 phases: thrombin generation, clot firmness, and clot stabilization (figure). Thrombin generation is determined by enzymatic coagulation factors and can be modified by the biochemical environment, anticoagulants, inhibitors, and coagulation factor deficiencies. This phase is represented by CT (clotting time) in ROTEM.2 Clot firmness is determined by fibrin polymerization, platelet aggregation, and platelet-fibrin-interaction. This can be modified by factor XIII (FXIII) and colloids.2,3 This phase can be altered by deficiency of any of these components and corresponds to early (amplitude 5 or 10 minutes after CT: A5 and A10) and late clot firmness parameters (maximum clot firmness: MCF) in ROTEM.2 Clot stabilization is determined by fibrinolysis, FXIII, and platelet-mediated clot retraction, and is represented by maximum lysis (ML), lysis onset time (LOT), and lysis index at 30, 45, and 60 minutes after CT (LI30, LI45, and LI60).2 FIBTEM is the most sensitive and specific assay for the detection of hyperfibrinolysis.4 The combination of EXTEM (sensitive to fibrinolysis and platelet-mediated clot retraction), FIBTEM (not sensitive to platelet-mediated clot retraction but very sensitive to fibrinolysis), and APTEM (not sensitive to fibrinolysis but to platelet-mediated clot retraction) can be used to differentiate between hyperfibrinolysis and platelet-mediated clot retraction.5 Fortunately, the latter is not associated with bleeding and does not require therapy with antifibrinolytics6.”1 (figure)

The 10 step algorithm is presented below, and don’t panic, it’s much easier to understand than the classic coagulation cascade! We would recommend downloading this algorithm and posting it in areas of the OR in which massive hemorrhage is expected like in the cardiac, trauma, and major orthopedic surgery ORs. Further, it may make sense to add it to your massive transfusion blood cooler. Additionally, I (MY) am reaching out to SPA’s checklist and Pedi Crissis app committee to try to get this incorporated into our checklists and app in their next versions under the massive hemorrhage tab.

What are some highlights? In early goal directed therapy “consider the use of coagulation factor concentrates and/or hemostatic drugs instead of allogeneic blood components since liberal transfusion has been associated with severe adverse events. Early administration of tranexamic acid (TXA) within the first 3 hours after injury or delivery in trauma induced coagulopathy and postpartum hemorrhage. Fibrinogen concentration should be monitored early, and in the presence of hypofibrinogenemia, supplementation should be performed with fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate. Conventional clotting tests such as Complete Blood Count (CBC) should be performed to assess platelet count, PT/INR, and aPTT to monitor the anticoagulant effects, anti-Xa activity for low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). D-dimer is helpful for differentiating disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) from other conditions potentially associated with a low platelet count, low fibrinogen, and prolonged clotting times, such as in liver disease.”1

“Once the coagulopathy is identified, an individualized treatment should be considered in a retrograde way following the advanced trauma life support (ATLS) concept of “treat first what kills first” ( Figure above) Accordingly, we should firstly stabilize the clot by blocking hyperfibrinolysis, secondly improve clot firmness, and third improve thrombin generation. In this case, the order of factor replacement may compromise the result of bleeding control.”1

Clot stabilization. Use TXA EARLY. As discussed in previous PAADs, the dosing of TXA is very institutional biased. However, we think a 30 minute loading dose of 10-30 mg/kg followed by a continuous infusion of 5-10 mg/kg/hour is the best evidence based guidance in pediatrics. 7,8

Clot firmness: Fibrinogen supplementation should be performed early and guided by ViscoElastic Testing to improve clot firmness and to reduce transfusion requirements. Eventhough FFP has all of the coagulation factors in physiologic concentratins it may be insufficient. Thus, “current guidelines recommend using lyophilized fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate to restore the fibrinogen concentration.9”1 Because clot firmness can also be impaired by thrombocytopenia and/or severe platelet dysfunction, platelet function tests in addition to VET should also be performed (see reproduced figure above)

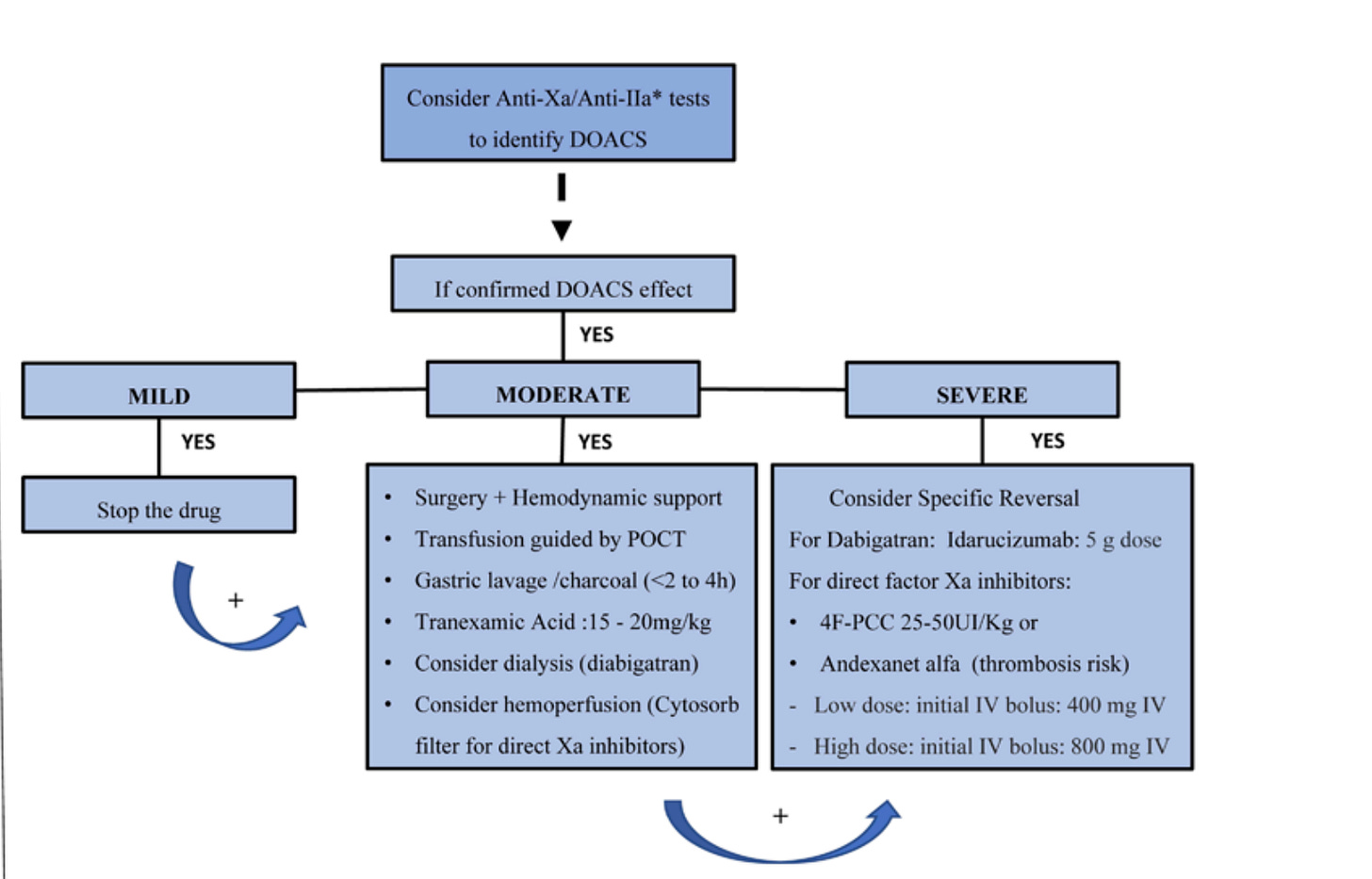

Thrombin Generation: “The impairment in the thrombin generation can be the result of a coagulation factor deficiency, or the effect of anticoagulants, and can be accessed by ROTEM CT. Prolonged clotting time (CT) results should only be considered to trigger FFP or Four-Factor Prothrombin Complex Concentrate (4F-PCC) administration in bleeding patients with normal FIBTEM clot firmness. 4F-PCC is a human plasma-derived coagulation factor concentrate, produced by ion-exchange chromatography with viral inactivation, and contains vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors and inhibitors: factor II, VII, IX, X as well as AT, protein C, S, Z, and heparin. Its Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared indication is the reversal of the effect of vitamin K- antagonists (VKA), whereas in Europe it is approved for the prophylaxis and therapy of bleeding due to vitamin K-dependent factor deficiencies.”1

Again, we didn’t do full justice to this article and would urge you to carefully read it or discuss in a journal club or at a conference. Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

1. Crochemore T, Görlinger K, Lance MD. Early Goal-Directed Hemostatic Therapy for Severe Acute Bleeding Management in the Intensive Care Unit: A Narrative Review. Anesthesia and analgesia 2024;138(3):499-513. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000006756.

2. Napolitano M, Siragusa S, Mariani G. Factor VII Deficiency: Clinical Phenotype, Genotype and Therapy. J Clin Med 2017;6(4) (In eng). DOI: 10.3390/jcm6040038.

3. Santos AS, Oliveira AJF, Barbosa MCL, Nogueira J. Viscoelastic haemostatic assays in the perioperative period of surgical procedures: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of clinical anesthesia 2020;64:109809. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.109809.

4. Yoshii R, Sawa T, Kawajiri H, Amaya F, Tanaka KA, Ogawa S. A comparison of the ClotPro system with rotational thromboelastometry in cardiac surgery: a prospective observational study. Sci Rep 2022;12(1):17269. (In eng). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-22119-x.

5. Hartmann M, Lorenz B, Brenner T, Saner FH. Elevated Pre- and Postoperative ROTEM™ Clot Lysis Indices Indicate Reduced Clot Retraction and Increased Mortality in Patients Undergoing Liver Transplantation. Biomedicines 2022;10(8) (In eng). DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines10081975.

6. Katori N, Tanaka KA, Szlam F, Levy JH. The effects of platelet count on clot retraction and tissue plasminogen activator-induced fibrinolysis on thrombelastography. Anesthesia and analgesia 2005;100(6):1781-1785. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/01.Ane.0000149902.73689.64.

7. Tan GM, Murto K, Downey LA, Wilder MS, Goobie SM. Error traps in Pediatric Patient Blood Management in the Perioperative Period. Paediatric anaesthesia 2023;33(8):609-619. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/pan.14683.

8. King MR, Staffa SJ, Stricker PA, et al. Safety of antifibrinolytics in 6583 pediatric patients having craniosynostosis surgery: A decade of data reported from the multicenter Pediatric Craniofacial Collaborative Group. Pediatric Anesthesia 2022;32(12):1339-1346. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14540.

9. Kietaibl S, Ahmed A, Afshari A, et al. Management of severe peri-operative bleeding: Guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care: Second update 2022. European journal of anaesthesiology 2023;40(4):226-304. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/eja.0000000000001803.