We are thrilled to bring you today’s PAAD – not purely a clinical practice read, but a hybrid of clinical work (airway management) and human factors engineering and quality improvement (error traps and how to avoid them). Based on Judit’s formal training (Masters in Patient Safety Leadership), and our shared love of complex airways in aerodigestive, laryngotracheal reconstruction, epidermolysis bullosa, neonatal airway lesions and quality improvement, we are thrilled to bring some conversation about this opportunity we have to improve our practice.

We are grateful to our friends and colleagues who wrote this article, as we think it is a good “initial step” in finding the commonality and developing a shared vocabulary between what we do (airway management) and what we know to be routine in industry from a human factors engineering work and quality improvement standpoint. We also think there is a fair amount of work that has to be done if we, as a pediatric specialty, want to apply these proven and effective approaches to our own practice with the goal of improving our care of pediatric patients.

So, we will review the original article as well as provide a set of compelling “extra reads” that we consider to be the ‘gold standard’ of error traps literature, and a primer to get us all aligned on Error Traps and their management. Happy reading!

Original Article:

Lisa Sohn, James Peyton, Britta S von Ungern-Sternberg, Narasimhan Jagannathan. Error traps in pediatric difficult airway management. Pediatr Anesth. 2021 September 3. DOI: 10.1111/pan.14289

The article written for today’s PAAD serves to frame one of our toughest scenarios that pediatric anesthesiologists embrace – the difficult airway. A lot has been studied, written and published about the pediatric difficult airway, most consistently by the dedicated group of anesthesiologists that founded, comprise, and run the Pediatric Difficult Intubation Collaborative (PeDI-C) which has exploded onto the pediatric anesthesia scene over the last 10 years. Each of the authors of this paper are part of the PeDI-C, as are we.

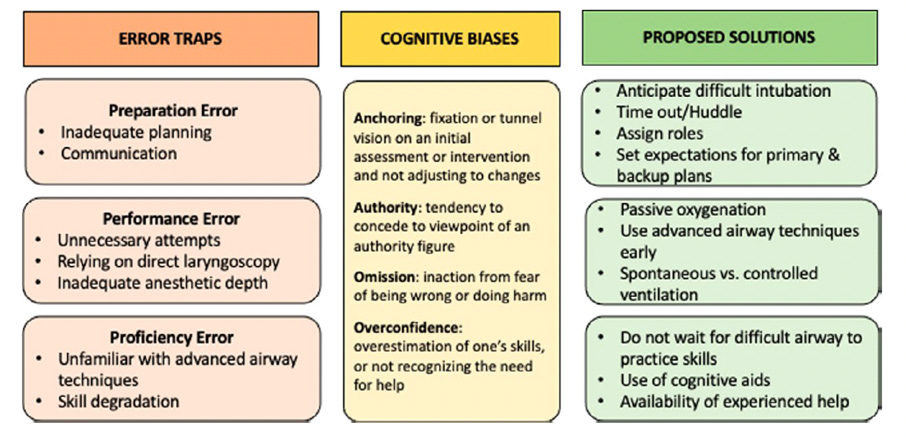

This paper takes a broad review approach to pediatric difficult airway management and divides it into three “types” of error traps: Preparation error, Performance error, and Proficiency error. It then follows each type of error with a proposed “solution”.

The first error trap discussed is Preparation Error for which the authors provide a couple of common examples of preparation failures we encounter (or create) as pediatric anesthesiologists: lack of anticipation, need for delegation and absence of teamwork. The proposed solutions by the authors include anticipating the difficult intubation, performing a huddle or timeout prior to management, assigning roles, and setting expectations for primary and back up plans. We appreciate that our colleagues chose to focus on identification, planning, and preparation as a critical juncture to catch/avoid the pitfalls of a difficult airway or difficult intubation – which we all agree is an important first step in difficult airway management of pediatric patients.

The second error trap identified by the author group is Performance Error. They list typical errors made during difficult airway management: repeated identical airway attempts (especially DL), failing to move quickly to alternative techniques, persisting with the same airway operator multiple times, and neglecting to use passive oxygenation. The authors then present solutions to falling victim to a performance error: use of passive oxygenation (always?), use of any other advanced airway technique on first attempt in neonates (take home: use anything but DL) and ensure deep anesthesia prior to airway attempt.

The third error trap labelled by the paper is Proficiency Error for which the authors list examples: inability to perform the advanced technique, lack of familiarity with advanced equipment set up (this might be a preparation error rather than proficiency), or failing to recognize the need for help or one’s own ‘failure’ of a task (overconfidence bias or Dunning-Kruger effect). The authors call for individual approaches and institutional approaches in the form of recurring workshops, revising protocols, use of cognitive aids, identifying and recruiting experienced/experts within an institution to serve as resources, case reviews and a debriefing system.

The meat of the article is summarized in figure 2 (see below). That table is fantastic with one caveat: the proposed solution (green) column is a mix of actual solutions (huddles, checklists, cognitive aids) and desired outcomes (early recognition of the difficult airway, applying passive oxygenation, maintaining skills). We would like to make it a “4 column” figure, separating the green column into two sections – desired outcomes as one column followed by actual solutions that can be applied to achieve the desired outcomes.

Overall, our assessment of this paper is that it is a great summary of where we usually fail with difficult airways and a good first step in starting the conversation about a framework of how and with what vocabulary to approach errors during airway management. Simply choosing to include this paper in the PAAD may serve as a “call to educate” on a proper application of human factors engineering to identifying and then preventing error traps, how to identify and eventually extinguish various biases encountered in human work, and ultimately setting up systems to prevent human error (by making it impossible to do the wrong thing, and easy to do the right thing). There is plenty written in industry, aviation, and human factors engineering works to guide our application of error traps in pediatric anesthesia practice – and to give us a shared vocabulary, common and structured approach that we can then apply across many domains of our clinical practice. We need to properly apply that industry work to our field; this will take time, education, and commitment by all of us.

If this type of work interests you – and we hope it will, because we believe this is the future of lasting improvement of our specialty! – we recommend reading the following three articles to gain a basic working knowledge and application of human factors engineering and error traps.

Additional Reference / “Gold Standard” Article on Error Traps for structured error traps education:

1st: James Reason. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000 Mar 18; 320(7237): 768–770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768, PMID: 10720363.

2nd: Sidney W A Dekker. Reconstructing human contributions to accidents: the new view on error and performance. J Safety Res. Fall 2002;33(3):371-85. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4375(02)00032-4. PMID: 12404999.

3rd: Jan K. Wachter, Patrick L. Yorio. Human Performance Tools: Engaging Workers as the Best Defense Against Errors & Error Precursors. Professional Safety. January 2013; 58(2): 54-64.