Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a group of rare epithelial disorders caused by abnormal or absent structural proteins at the epidermal-dermal junction. Its severity is very variable; some patients can lead relatively normal lives others die in infancy. It is often a terribly disfiguring disease where the slightest skin contact (think ECG leads, mask airway pressure, taping an IV, essentially all the things we routinely do) can cause terrible harm. I had only seen a couple of these patients over the 35 years I worked at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. When I arrived at Colorado there were a lot of these patients and they were treated by a specialized, dedicated subset of anesthesia attendings led by Drs. Judit Szolnoki, Melissa Brooks-Peterson (the first and last authors of today’s PAAD) and many others. Because their experience was so unique and extensive, and there was so little information about the perioperative management of these patients, I suggested and mentored (Ok, really pestered/cajoled/harangued) them into writing up their experience and associated perioperative outcomes. Indeed, I was planning to write this PAAD when their paper was published in print (it was published on-line ahead of print last September). However, because a second paper on the anesthetic management of adults with EB was just published in this month’s Anesthesia and Analgesia, I thought it would be a good idea to write up the pediatric EB paper first and follow with the second adult paper later this month. Finally, a picture is worth a thousand words. The article has some excellent patient photographs demonstrating many of the issues discussed in the paper and today’s PAAD. You’ll need to download the article to see these pictures. Myron Yaster MD

Original article

Melissa Brooks Peterson, Kim M Strupp, Megan A Brockel, Matthew S Wilder, Jennifer Zieg, Anna L Bruckner, Alexander M Kaizer, Judit M Szolnoki. Anesthetic Management and Outcomes of Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa: Experience at a Tertiary Referral Center. Anesth Analg. 2021 Sep 30. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005749. Online ahead of print. PMID: 34591805

In this retrospective single institution review, the authors describe their institutional experience, methods, and outcomes with 37 EB patients who underwent 202 general anesthetics between 2011 and 2016. Some background: “In the most severe yet survivable subtypes of EB, functionality declines progressively owing to contractures of the skin and mucosal surfaces, chronic anemia, and infections. Chronic anemia in this population is multifactorial and includes anemia of chronic disease, blood, iron, and protein loss from open wounds on the skin, erosions in the intestinal tract, poor iron intake, and poor nutrient absorption. The blisters and wounds heal slowly, and extensive skin loss, scarring, and sepsis are common. Contractures can develop on the flexor surfaces of the neck, limbs, and digits. The fingers and toes fuse together, causing a mitten-type deformity called pseudosyndactyly that restricts dexterity and has a major impact on function. Further, accompanying anemia of chronic disease often necessitates regular venipuncture, transfusions, and iron infusions. Finally, malignancy, most commonly aggressive squamous cell carcinoma, is the leading cause of death in adolescents and adults with recessively inherited DEB (RDEB). Other causes of death in patients with severe forms of EB include malnutrition, sepsis, and respiratory failure. Simply put, EB is a terrible, horrific disease. Any pediatric anesthesiologist who has come across one of these special patients in their time of need will never forget it. As my former mentor the late Jack Downes always said, “the single most important attribute that a pediatric anesthesiologist/intensivist must have is compassion”.

More on the disease and its impact on general anesthesia. The mucosa in the mouth is histologically similar to that of the skin, except that superficial keratin is absent. Simple mastication erodes the mucosa, resulting in progressive and severe microstomia and ankyloglossia due to scarring. Patients with RDEB experience recurrent and progressive esophageal stricture formation leading to dysphagia, malnutrition, and need for gastrostomy tube. Esophageal strictures in patients with RDEB often require serial balloon dilation with fluoroscopic guidance. These airway and esophageal changes result in progressively difficult airway management, deterioration of nutritional status, and poor dental hygiene. General anesthesia is frequently required to manage these gastrointestinal disease manifestations, as well as procedures for scar and contracture release, pseudosyndactyly release, and dental rehabilitation.”

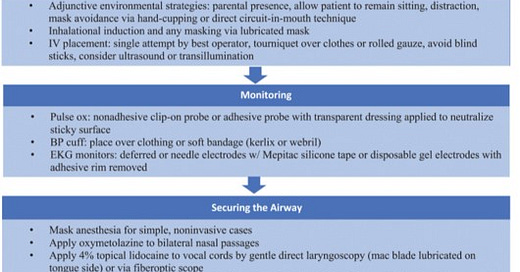

The authors describe a standardized approach (see figure below) by a specialized, dedicated subset of expert anesthesiologists. The key is the avoidance of all friction and shear forces that can cause bullae to develop with subsequent catastrophic sloughing. The highly specific and reproducible method of airway management is the second main take-away. Some highlights from the paper:

Patient positioning: “When moving patients from a crib/stretcher to the operating room (OR) table (and vice versa), it is essential to avoid sliding a patient across any surface. The patient should be levitated, often with the aid of a draw sheet placed under the patient, moved over, and placed back down without any dragging”.

Induction: “Inhalation induction of anesthesia before intravenous (IV) placement is our preferred approach in most cases. Although often difficult to intubate, these patients are typically easy to mask ventilate with limited-to-no manipulation of the jaw or face because their ankyloglossia lessens the occurrence of base of tongue obstruction of the hypopharynx. We encourage patients to position themselves comfortably before induction with the aid of family members when possible.”

IV access is difficult. Patients and parents can serve as allies in identifying the best IV site. Ultrasound and transillumination are often necessary. How to secure the IV? “We secure IV catheters using minimal strip(s) of a special silicon-based dressing, Mepitac (Molnlycke Health CareAB), which separates easily from the skin with water. We then indirectly secure the IV and tubing by wrapping it with rolled gauze and taping only on the gauze”.

Monitoring: For pulse oximetry “options include either a non-adhesive clip-on probe or a sticky probe rendered adhesive-free with 3M Tegaderm Transparent Film Dressing or cotton. In patients who have severe mitten deformity and loss of digits, an alternative protuberance such as the ear lobe, lip, or nose is used.” “Blood pressure cuffs are well tolerated when placed over clothing or soft bandages”. EKG leads are tricky and are often omitted. Techniques to secure needle electrodes or disposable gel electrodes after the adhesive rim has been trimmed are described.

Airway: “Mouth opening becomes increasingly small (as small as millimeters in the most severely affected patients), and recurrent oral instrumentation perpetuates scarring and deformation”. Mask ventilation is relatively easy. They use a “special lubricant” (3 packets of surgilube + 1 tube of eye ointment) which is liberally applied to the face mask. Intubation is often accomplished by asleep nasal fiberoptic techniques. Nasal intubation is preferred because “the nasal passages are lined with respiratory epithelium, which is less likely to blister that the stratified squamous epithelium of the oral mucosa.” Passive oxygenation or continued inhalation agent administration during intubation may be accomplished through the placement of a soft nasal airway with an ETT adapter in the opposite nare. The nasal endotracheal tube is secured indirectly and never taped or tied. The nasotracheal tube is best secured to a padded headdress with no tape applied to the face (see photo in article). Supraglottic devices are avoided (difficult or impossible to place because of very small mouth opening). Patients are extubated awake in the operating/procedure room.

Using these techniques this specialized, dedicated, well-rehearsed team anesthetized these vulnerable and complex EB patients with a very low incidence of complications.

If any of you have further questions, suggestions, insights please send to me (myasterster@gmail.com) or to John Fiadjoe and we’ll post them in the reader response PAAD. Myron Yaster MD

So thankful for this publication.