Environmental Effects of Propofol Versus Sevoflurane for Maintenance Anesthesia

Jake C Graffe DO, Diane Gordon MD, Elizabeth E Hansen MD PhD

Original article

Kalmar AF, Rex S, Vereecke H, Teunkens A, Dewinter G, Struys MMRF. Environmental Effects of Propofol Versus Sevoflurane for Maintenance Anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2025 Mar 1;140(3):740-742. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000007248. Epub 2024 Oct 16. PMID: 39413035.

Anesthesiologists increasingly face questions about the environmental impacts of their practice. Today’s PAAD examines the comparative environmental footprint of propofol TIVA (total intravenous anesthesia) versus sevoflurane for maintenance of anesthesia.1 With climate change widely recognized as a global health emergency, understanding the environmental impact of our anesthetic choices has, in our opinion, become a professional imperative. This work builds upon years of study, including the landmark 2012 paper by Sherman et al which found a significantly smaller environmental footprint of TIVA compared to inhaled anesthetics - even when considering plastic waste and energy requirement - in a life cycle assessment (LCA).2 Concerns have been raised about the ecotoxicity of propofol on aquatic species and the additional plastic waste generated by TIVA, and Kalmar’s paper provides important insights into both.

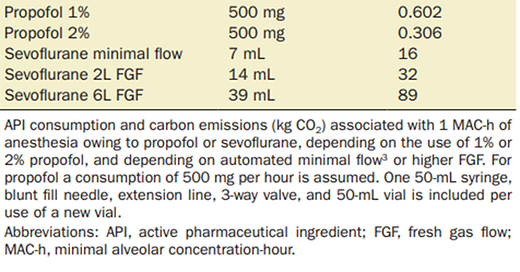

Sherman’s LCA, along with other research,3 forms the basis of the Gassing Greener App (apple and android), a smartphone app that calculates emissions for your anesthetic based on utilization of inhaled or IV agent, dosages, concentrations, and fresh gas flows. To meaningfully compare the environmental impacts of propofol and sevoflurane, we must first understand their typical clinical usage in terms of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API). The dosing comparison alone provides striking context: one MAC-hour of anesthesia requires approximately 0.5g of propofol (50ml = 500mg) compared to 11 - 59g of sevoflurane (7- 39ml, depending on fresh gas flow rates). This represents a marked difference, with sevoflurane being administered at 20-120 times more API than propofol for the same anesthetic effect.

The ecotoxicity of a chemical generally falls into two main categories: Surface water/groundwater contamination and atmospheric pollution. The article summarizes the ecotoxicities of propofol and sevoflurane under these two categories based on past studies conducted by our colleagues in Europe. Studies in higher organisms (e.g., fish, birds, reptiles) have shown that propofol exhibits similar pharmacokinetics to that measured in humans. Additionally, environmental risk assessments of propofol entering wastewater “remain consistently well below the threshold for any discernible adverse effects]”4 including a 2012 study from a Swedish hospital that showed propofol comprised only 0.01% of the total amount of 70 different pharmaceuticals whose presence in hospital wastewater were assessed.5

On the other hand, 5% of sevoflurane uptake is renally excreted as hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), or about 240 mg per hour of maintenance anesthesia. HFIP is a so-called “forever chemical” (or PFAS), meaning that it persists for exceptionally long periods in closed-water bodies, leading to a steady increase in concentration. While HFIP per se is not considered a significant environmental hazard, knowledge gaps remain “as to its persistence in hospital wastewater.” HFIP eventually degrades to trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), a known “forever chemical”. TFA is resistant to all forms of degradation, both natural (e.g., oxidative, reductive, biologic) and artificial (e.g., ozonation).6

Furthermore, atmospheric sevoflurane also eventually releases one molecule of TFA per molecule of sevoflurane, creating a dual pathway for environmental contamination through both direct excretion and atmospheric degradation. So, interestingly, sevoflurane seeds TFA into the environment by way of both land and air. It should be noted that since 63% of propofol is renally cleared, approximately 250 mg of both propofol and sevoflurane enter wastewater systems per hour of maintenance anesthesia. The take-home point here, though, is that sevoflurane metabolites and their degradation products persist in the environment and may pose a hazard, while propofol and its metabolites do not exhibit such a concerning presence.

As this readership knows, the greenhouse gas impact presents the most significant contrast between these agents. The production and disposal of propofol administration supplies (including vials, syringes, extension lines, and valves/claves) generates approximately 776g CO₂ equivalent emissions per hour of anesthesia, assuming glass and plastics are not recycled and a new set of syringes and a propofol 1% vial are used hourly. However, just 1mL of sevoflurane traps as much atmospheric heat over 20 years (i.e., “global warming potential”, or GWP20) as 2,134g of CO₂, resulting in a 27-300-fold greater carbon-equivalent emission compared to propofol-based anesthesia. The GWP20 values of 1 MAC-h sevoflurane extrapolated to various FGF rates are shown in terms of kg CO2 in the table below. Note the stark comparison to 1 MAC-h of propofol.

Importantly, the global standard metric for carbon-equivalent emissions used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and cited by the EPA is GWP100, not GWP20. That is, atmospheric pollutants such as sevoflurane are quoted by these institutions in terms of their carbon-equivalent atmospheric heat-trapping potential over a 100-year period, although the atmospheric lifetime of volatile anesthetics is short and thus their heat-trapping effects are concentrated over the first few years after their release.

Despite waste anesthetic gas mitigation strategies, sevoflurane contributes to climate change due to its high global warming potential. Propofol, on the other hand, does not contribute directly to atmospheric emissions. Even when considering the full life cycle, including production, transport, and disposal of the drug as well as the syringes, tubing and pumps to deliver it, the overall environmental impact of propofol anesthesia remains far lower than that of sevoflurane. This paper challenges the perception that propofol TIVA has a comparable environmental footprint due to waste handling and disposal of propofol when, in clinical practice, the carbon footprint of propofol-based anesthesia is markedly lower than that of volatile agents, thus making it the more environmentally sustainable anesthetic choice when both options are available and clinically appropriate. While this article is based on anesthetics administered to the average adult patient, the environmental take-home message here is perhaps even more urgent in the context of pediatric anesthesia practice, where high-emission inhaled inductions are far more common and the equi-anesthetic doses of propofol are often much lower overall because children weigh less than adults.

Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

[1. Kalmar AF, Rex S, Vereecke H, Teunkens A, Dewinter G, Struys M. Environmental Effects of Propofol Versus Sevoflurane for Maintenance Anesthesia. Anesthesia and analgesia 2025;140(3):740-742. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000007248.

2. Sherman J, Le C, Lamers V, Eckelman M. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of anesthetic drugs. Anesthesia and analgesia 2012;114(5):1086-90. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824f6940.

3. Parvatker AG, Tunceroglu H, Sherman JD, et al. Cradle-to-Gate Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Twenty Anesthetic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Based on Process Scale-Up and Process Design Calculations. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2019;7(7):6580-6591. DOI: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05473.

4. Waspe J, Orr T. Environmental risk assessment of propofol in wastewater: a narrative review of regulatory guidelines. Anaesthesia 2023;78(3):337-342. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/anae.15967.

5. Falås P, Andersen HR, Ledin A, la Cour Jansen J. Occurrence and reduction of pharmaceuticals in the water phase at Swedish wastewater treatment plants. Water Sci Technol 2012;66(4):783-91. (In eng). DOI: 10.2166/wst.2012.243.

6. Freeling F, Björnsdotter MK. Assessing the environmental occurrence of the anthropogenic contaminant trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2023;41:100807. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsc.2023.100807.

The practice of pediatric anesthesia is unlikely to eliminate sevoflurane mask induction in favor of awake IV placement for intravenous induction. This raises the question of whether or not it is environmentally better to transition to propofol TIVA after administering Sevoflurane for induction. Managing mask induction to minimize the environmental impact of the induction process is important. (See Gordan D, Feldman JM. Environmentally Responsible Mask Induction Best Practice and Research Clinical Anaesthesiology. Published online. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2025.02.001). The relevant environmental impact comparison to propofol TIVA after mask induction with Sevoflurane would compare propofol administered and wasted (including plastic administration supplies) to Sevoflurane maintenance using an effective low flow technique.

More information is needed to understand it there is an environmental advantage to Propofol TIVA in pediatric anesthesia following mask induction!