Original article

Meng L, Rasmussen M, Abcejo AS, Meng DM, Tong C, Liu H. Causes of Perioperative Cardiac Arrest: Mnemonic, Classification, Monitoring, and Actions. Anesth Analg. 2024 Jun 1;138(6):1215-1232. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006664. Epub 2023 Oct 3. PMID: 37788395.

Many years ago, Dr. Joe Cravero of Boston Children’s Hospital fame, while discussing sedation catastrophes at a national meeting stated something along these lines: “you can build an airplane in which everyone survives the crash…the only problem is, that airplane can’t fly”. The idea: you can put up as many rules, safety measures and guard rails you can think of to prevent sedation catastrophes from occurring, but if sedation actually occurs there will occasionally be respiratory and cardiovascular disasters. The goal therefore is to not only limit these events but to ensure successful rescue when they do occur with effective and immediate CPR and rapid identification and treatment of the underlying causes.

A perioperative cardiac arrest (POCA) event will occur to everyone reading today’s PAAD at some point in their career. Successful resolution and outcomes rely on prompt recognition of the crisis and the ability to rescue. In today’s PAAD. Meng et al.1 propose a novel approach to rescue when a POCA event occurs. Surprisingly to me, they missed an opportunity to discuss crisis checklists and memory aids, like the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia’s Pedi Crisis app V 2 which is available for both iPhone and Android users. After declaring an emergency and calling for help the very first thing you need to do is open the app! If you haven’t already downloaded this app, stop reading today’s PAAD and do it immediately! Why is this so important? Life-threatening, critical events in the operating room are managed in a fast-paced, high-distraction atmosphere, often with little time to think or deliberate about treatment options. Success often depends on implementing a team approach with well-rehearsed, systematic, evidence-based assessment and management protocols within the first moments of presentation.2 Yet, because life-threatening crises are rare and human performance can be compromised under stressful conditions,3-6 even expert clinicians may omit or delay key actions, with detrimental effects on patient morbidity and mortality.7 In multiple simulation-based studies, correct performance of key actions increased when emergency manuals, crisis checklists, or cognitive aids were used.8-11

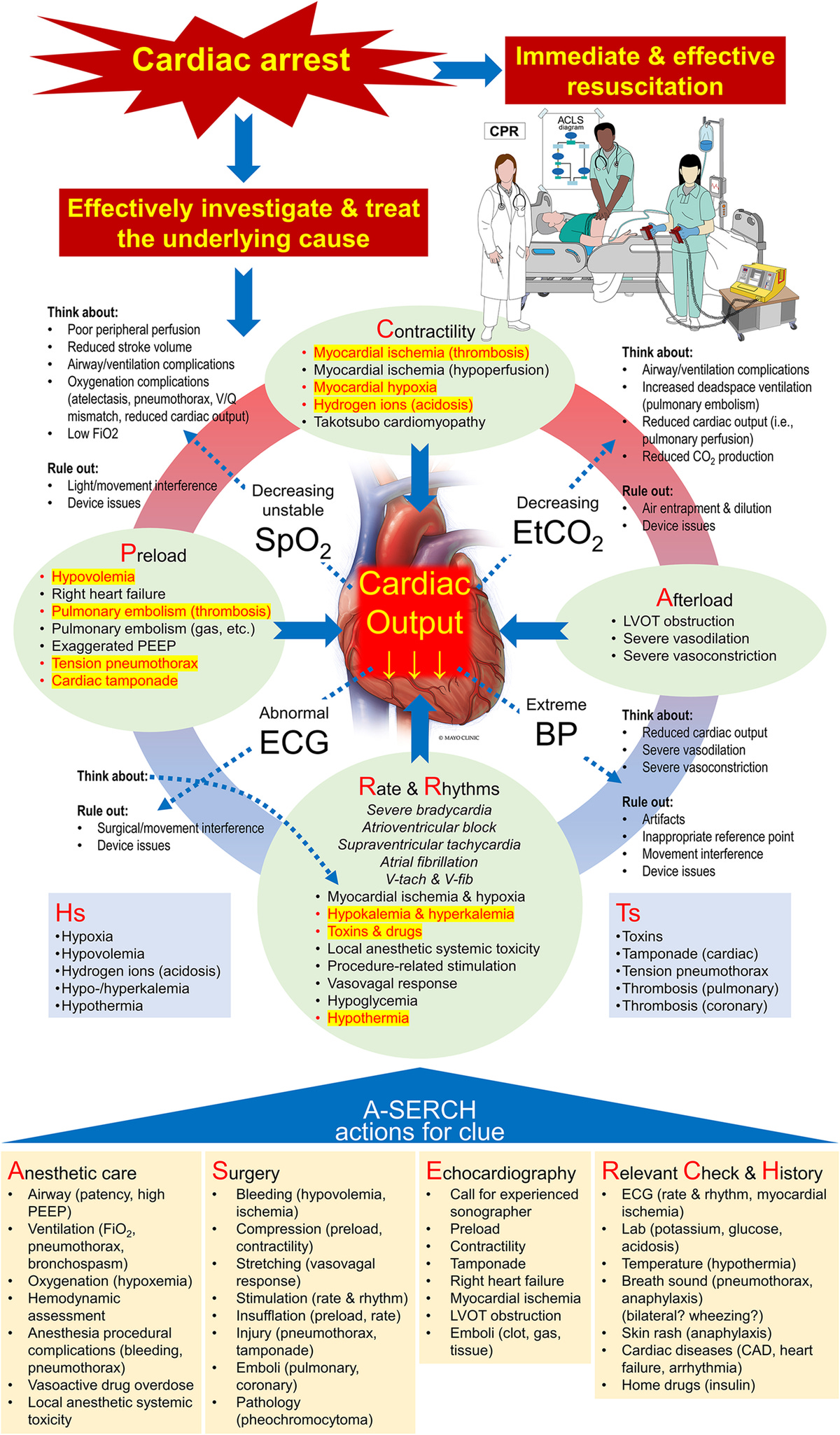

A common mnemonic used in the Pedi crisis app and in the American Heart Association Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) courses is the 5 Hs and Ts: Hypoxia, Hypovolemia, Hydrogen ions (acidosis), Hypo-/Hyperkalemia, and Hypothermia (Hs) and Toxins (anesthetic drug overdose), Tamponade (cardiac), Tension pneumothorax, Thrombosis (pulmonary), and Thrombosis (coronary) (Ts). Meng et al. propose a modification to assess “preload-contractility-afterload-rate and rhythm (PCARR)” by relying heavily on the use of echocardiography, electrocardiography, pulse oxygen saturation, end-tidal carbon dioxide, and blood pressure to identify clues to the underlying cause of POCA.1

Because I try to keep the PAADs to 5-6 minute reads, it is beyond my ability to do justice to this article in the PAAD format. I’d recommend taking a few minutes to quickly review and scan the article in its entirety. However, if you don’t have the time or ability to download the entire article, there are 2 fantastic figures that I’ve copied below that pretty much summarize the article and I think should be copied and placed in all of your anesthetizing locations, perhaps next to the SPA crisis checklists.

Finally, as discussed in several recent PAADs, ultrasonography (point of care ultrasonography, POCUS) is rapidly becoming an essential tool in today’s practice of pediatric anesthesiology. Using echocardiography during a cardiac arrest may be indispensable in diagnosing and treating the physiologic events underlying POCA. After reading today’s PAAD, I’ve spoken to Drs. Priti Dalal, Anna Clebone, Kim Strupp, and Barbara Burian to consider adding these figures or its content to the next version of the Pedi Crisis app and checklists. What do you think about the use of POCUS in a POCA? Do you have the availability and expertise to use it? Send your thoughts to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

1. Meng L, Rasmussen M, Abcejo AS, Meng DM, Tong C, Liu H. Causes of Perioperative Cardiac Arrest: Mnemonic, Classification, Monitoring, and Actions. Anesthesia and analgesia 2024;138(6):1215-1232. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000006664.

2. McEvoy MD, Field LC, Moore HE, Smalley JC, Nietert PJ, Scarbrough SH. The effect of adherence to ACLS protocols on survival of event in the setting of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2014;85(1):82-7. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.09.019.

3. Bloomstone JA. Humans fail, checklists don't. J Clin Anesth Manag 2015;1(1):doi http://dx.doi.org/10.16966/2470-9956.104. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16966/2470-9956.104.

4. Hales BM, Pronovost PJ. The checklist--a tool for error management and performance improvement. J Crit Care 2006;21(3):231-5. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.06.002.

5. Prielipp RC, Birnb ach DJ. Pilots use checklists, why don't anesthesiologists? The future lies in resilience. Anesthesia and analgesia 2016;122(6):1772-5. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000001320.

6. Wheelock A, Suliman A, Wharton R, et al. The impact of operating room distractions on stress, workload, and teamwork. Ann Surg 2015;261(6):1079-84. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/sla.0000000000001051.

7. Weinger MB, Banerjee A, Burden AR, et al. Simulation-based Assessment of the Management of Critical Events by Board-certified Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 2017;127(3):475-489. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/aln.0000000000001739.

8. Field LC, McEvoy MD, Smalley JC, et al. Use of an electronic decision support tool improves management of simulated in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2014;85(1):138-42. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.09.013.

9. Harrison TK, Manser T, Howard SK, Gaba DM. Use of cognitive aids in a simulated anesthetic crisis. Anesthesia and analgesia 2006;103(3):551-6. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/01.ane.0000229718.02478.c4.

10. Marshall S. The use of cognitive aids during emergencies in anesthesia: a review of the literature. Anesthesia and analgesia 2013;117(5):1162-71. (In eng). DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31829c397b.

11. Arriaga AF, Bader AM, Wong JM, et al. Simulation-based trial of surgical-crisis checklists. The New England journal of medicine 2013;368(3):246-53. (In eng). DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204720.