Balanced electrolyte solution with 1% glucose as intraoperative maintenance fluid in infants: a prospective study of glucose, electrolyte, and acid-base homeostasis

Myron Yaster MD and Francis Veyckemans MD

In a previous PAAD (04/12/2023: https://ronlitman.substack.com/p/remembering-the-classics-european ) one of the PAAD’s senior writers, Dr. Francis Veyckemans reviewed the classic European consensus paper by Sümpelmann et al1 on ideal IV maintenance fluid solutions to be used in pediatric anesthesia practice.

The ideal solution should 1) be isotonic to prevent the occurrence of hyponatremia due to excessive administration of free water and concomitant stress-induced increased ADH ; 2) its electrolytic content should be balanced (close to the plasma) to avoid hyperchloremic acidosis as when only 0.9% NaCl (normal saline) is used ; 3) it should contain enough glucose to avoid both hypo- and hyperglycemia, as well as increased lipolysis in infants when no glucose is administered, which turned out to be a 1% glucose concentration ; 4) it should contain metabolic anions (like acetate, lactate or malate) as bicarbonate precursors to avoid acid–base balance disturbances. Acetate was finally chosen because its metabolization is faster and more independent of liver function than lactate.

The primary aim of today’s PAAD study by Lindestam et al.2 was “to evaluate the incidence of hypoglycaemia when a balanced electrolyte solution containing 1% glucose is used intraoperatively as a maintenance infusion to infants (1-12 months of age) in anaesthetic practice, with lower infusion rates of maintenance fluid, shorter fasting times, and frequent use of neuraxial blocks. Secondary aims were to evaluate the incidences of hyponatraemia and hyperchloraemia, increased ketone body concentration, metabolic acidosis, and the influence of prolonged duration of preoperative fasting.”

Although the solutions used in today’s PAAD are commercially available in Europe, to the best of my knowledge 1% glucose containing solutions are not commercially available in the United States. However, they can be made by your pharmacy or by yourselves when patients who require glucose come to the OR. Myron Yaster MD

Original article

Lindestam U, Norberg Å, Frykholm P, Rooyackers O, Andersson A, Fläring U. Balanced electrolyte solution with 1% glucose as intraoperative maintenance fluid in infants: a prospective study of glucose, electrolyte, and acid-base homeostasis. Br J Anaesth. 2025 May;134(5):1432-1439. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2024.08.041. Epub 2024 Nov 5. PMID: 39505591.

“This prospective observational study was conducted at the Department of Paediatric Anaesthesia and Intensive Care at Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital, Karolinska University Hospital (Stockholm, Sweden) and at the Paediatric Section of the Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care of Uppsala University Hospital (Uppsala, Sweden), both tertiary referral centres for paediatric surgery.2 Infants 1-12 months of age undergoing surgery were given IV isotonic maintenance fluids with 1% glucose at infusion rates ranging from 4 mL/kg/h for minor surgery to 8mL/kg/h for major surgery with a higher infusion rate the first hour (10 mL/kg/h) to compensate for preoperative fasting. Blood gas and ketone body analysis were performed at induction and at the end of anaesthesia. Plasma glucose concentration was monitored intraoperatively.

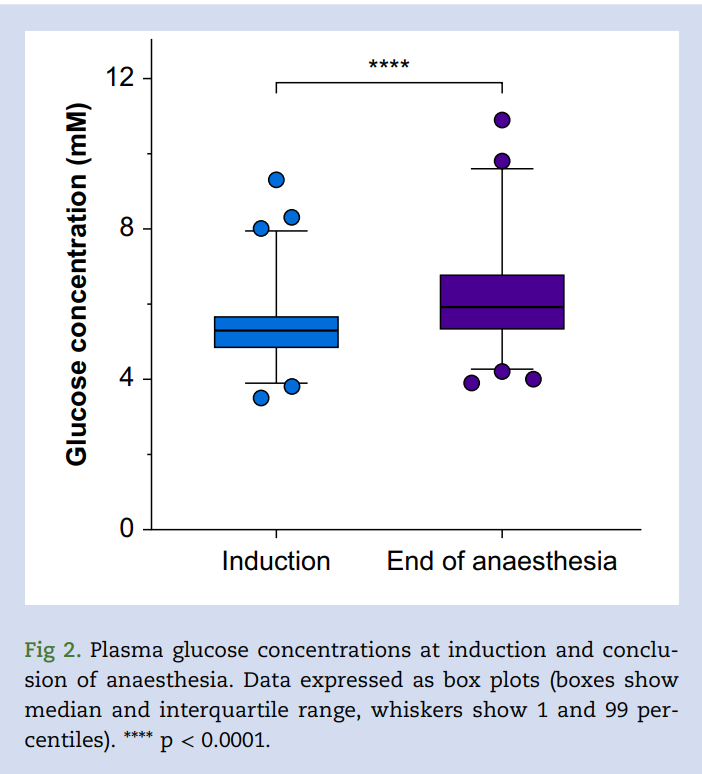

What did they find? “For the 365 infants included in this study, the median infusion rate of maintenance fluid was 3.97 (interquartile range 3.21-5.35) mL/kg/hour. Mean plasma glucose concentration increased from 5.3 mM at induction to 6.1 mM at the end of anaesthesia (mean difference 0.8 mM; 95% confidence interval 0.6-0.9, P <0.001). No cases of hypoglycaemia (<3.0 mM) occurred. Mean sodium concentration remained stable during anaesthesia. Chloride and ketone body concentration increased and base excess decreased, but these were within the normal range.”2

Perhaps most importantly, “Children < 3 months of age (n=123, 34%) had lower mean glucose concentrations at induction of anaesthesia (difference between means: 0.18 mM; 95% CI 0.01-0.30, P=0.033) and a larger mean intraoperative increase in glucose concentrations (difference between means 0.3 mM; 95% CI 0.1-0.6, P=0.005) compared with older infants.”2 “Mean plasma sodium concentration decreased throughout the intraoperative period but remained within (or close to) the normal range. The 3 patients with the lowest plasma sodium concentrations at the end of surgery were all hyponatraemic at induction.”2

The authors concluded that “In infants undergoing surgery, maintenance infusion with a balanced electrolyte solution containing 1% glucose, at rates similar to those proposed by Holliday and Segar3 is a safe alternative with regards to homeostasis of glucose, electrolytes, and acid-base balance.”2

Although the use of balanced electrolytic solutions with 1% glucose in children should be promoted, the results of this important study need to be interpreted carefully. First, patients at increased risk for hypoglycemia were excluded: “Exclusion criteria were prematurity with post-conception age < 44 weeks, metabolic or endocrine disease, liver disease affecting liver function, malnutrition, growth retardation (>2 standard deviations), ongoing beta blocker therapy, preoperative infusion of parenteral nutrition or glucose >6 h, and plasma glucose concentration < 3.0 mM at induction of anaesthesia.” Second, 4.3% of infants were hyperglycemic (glucose > 8.3 mM/L) and 6.6% were hyponatremic (Na < 135mM/L) at the end of surgery: such changes can thus still occur even when 1% glucose in a balanced salt solution is used. Last, observing no case of hypoglycemia does not mean that the risk is nil. If one applies the rule of 3, the maximum risk of hypoglycemia was 3/365, or 0.8%. This reminds us that IV fluids administered during anesthesia should not be considered as simple drugs carriers but that their content and volume should be carefully determined and measured. Moreover, the possible influence or anesthetic or adjuvant drugs should also be kept in mind. For example, in this study, the infants who received corticosteroids had a higher mean intraoperative increase in glucose concentration compared with those not receiving corticosteroids (difference between means 0.4 mM; 95% CI 0.1-0.7, P= 0.005). To conclude, we support the authors’ conclusions. However, since occurrence of asymptomatic preoperative or intraoperative hypoglycaemia cannot be excluded in rare cases, plasma glucose and sodium should be checked at induction and during anaesthesia in infants, especially during prolonged anaesthesia (>2 h).

And one final thought: When administering IV fluids to infants, please use infusion pumps and do not use gravity, free drip administration sets.

Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

1. Sümpelmann R, Becke K, Crean P, Jöhr M, Lönnqvist PA, Strauss JM, Veyckemans F: European consensus statement for intraoperative fluid therapy in children. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2011; 28: 637–9

2. Lindestam U, Norberg Å, Frykholm P, Rooyackers O, Andersson A, Fläring U: Balanced electrolyte solution with 1% glucose as intraoperative maintenance fluid in infants: a prospective study of glucose, electrolyte, and acid-base homeostasis. Br J Anaesth 2025; 134: 1432–1439

3. Holliday MA, Segar WE: The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957; 19: 823–32