Assessing Older Anesthesiologists

Myron Yaster MD, Barbara Burian PhD, Alan Jay Schwartz MD MSEd

On the first day of my anesthesiology resident rotation at the Philadelphia Veterans Administration hospital, the chief of service, the legendary Dr. Ted Smith, took me into his office and placed me in front of his new, first-generation Apple computer and made me play the computer game PONG. Since most of you were not yet born when it was first released in 1972 by Atari, PONG was a digital take on table tennis (ping-pong), where players use on-screen paddles to hit a ball across the screen. It was wildly popular, and its simplicity and accessibility helped establish video games as a new form of entertainment. On the first day of the rotation, Dr. Smith made me (and the other residents) practice the game for about 15 minutes to establish a baseline of my/our performance. For the rest of the month, he made me all of the other residents play the game shortly after our morning arrival to the ORs before we started our workday. If we were substantially off our average performance, he sent us home figuring we would also be off our game in the OR. I don’t think he ever used or published the data he collected but I’ve always wondered why no one else, either before or after, thought of doing the same thing or something like it.

Jump ahead 50 years. In today’s PAAD, Johnstone et al.1 provide a pro/con on neuropsychologic and specialty-specific vision and hearing testing to assess whether older physicians should be able to maintain their practice privileges. You may think this is not exactly a pediatric article but as our society and specialty practitioners age, its importance becomes increasingly important to ensure safety for all of our patients. And one more thing: and I want to be clear and upfront about it: I personally don’t think this issue should be limited to the aging anesthesiologist but should be considered, as Dr. Smith did, for all practicing anesthesiologists, and as Dr Johnstone included, for all practicing CRNAs (and AAs) regardless of their age. Myron Yaster MD

Original article

Johnstone R, Bader AM, Hepner DL. Assessing Older Anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 2025 May 1;140(5):1105-1110. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000007179. PMID: 39163252.

The argument for cognitive testing

Anesthesiology practice requires mental vigilance, (rapid) decision-making, and physical stamina and actions. As we age, predictable and progressive deterioration in mental, physical (particularly hearing, vision, and frailty), and behavioral functions occur.1,2 “Performance decreases may manifest in difficulties with comprehension, expression, or maintaining professional relationships, and reduce job performance and productivity. It can be argued that older physicians [and CRNAs and AAs] should be tested because their performance may impact patient safety. Proponents of cognitive testing of older [practitioners] generally view it as just a screening test that can become a comprehensive evaluation only when necessary.”1 Further, we often compare the field of anesthesiology to the airline industry which has mandatory retirement ages. Indeed, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration, requires air traffic controllers to retire at age 56 and commercial pilots at age 65 though there is some debate about whether this age limit should be raised to age 67.{Administration, #13936} “Many anesthesiologists [and CRNAs], though, desire to continue practicing clinically after age 65. Their reasons include beliefs that by continuing to practice they contribute to safe patient care, advance the specialty, and maintain their health. Older physicians who want to continue practicing often cite career satisfaction, a feeling of purpose, a strong work identity, and few interests outside of medicine. Obviously other reasons include continuing to earn income and enjoyment of their physician status.”1 We’re pretty sure many pilots and air traffic controllers feel the same! In fact, many commercial pilots do continue to fly professionally past age 65 but they have to change the types of aircraft they fly and the regulations they fly under (think business jets instead of Airbus 320s or Boeing 737s).{Administration, #13936} Finally, “although individual clinician performance may lead to adverse events, they occur primarily due to poorly designed systems, which allow predictable human errors to result.”1 Indeed, this argument can be made for both the pro and con sides of this debate.

The argument against cognitive testing

On the other hand, “people age biologically at different rates (eg, chronological age is not always the same as biological age), cognitive disorders vary greatly,3 and no reliable studies have shown that testing of physicians improves patient care. In fact, some physician skills and cognitive functions improve with age and experience. Indeed, a study using national data of Medicare beneficiaries in the United States found that patients treated by older surgeons had lower mortality than patients treated by younger surgeons.

These findings indicate that there is a significant learning curve in surgical practice, which can have a considerable impact on patients’ outcomes over time. Given that this was an observational study, these findings can also be attributed to surgeons selectively choosing to perform simpler procedures, working on lower complexity patients, or deciding whether to continue to operate at all, based on their perceived skills. Similar to surgeons, the clinical performance of anesthesiologists may improve as they gain skills and experience throughout their careers, yet it could also diminish due to decreases in manual dexterity or outdated knowledge..4”1

In the United States, “assessing just older physicians without evidence of impairment can constitute ageism, an unfair and discriminatory practice. Federal law prohibits discrimination based on age in programs and activities that receive federal funding. Some older physicians whose practice privileges have been restricted or denied due to age-based policies and testing have filed discrimination lawsuits against their institutions and won monetary awards.”1

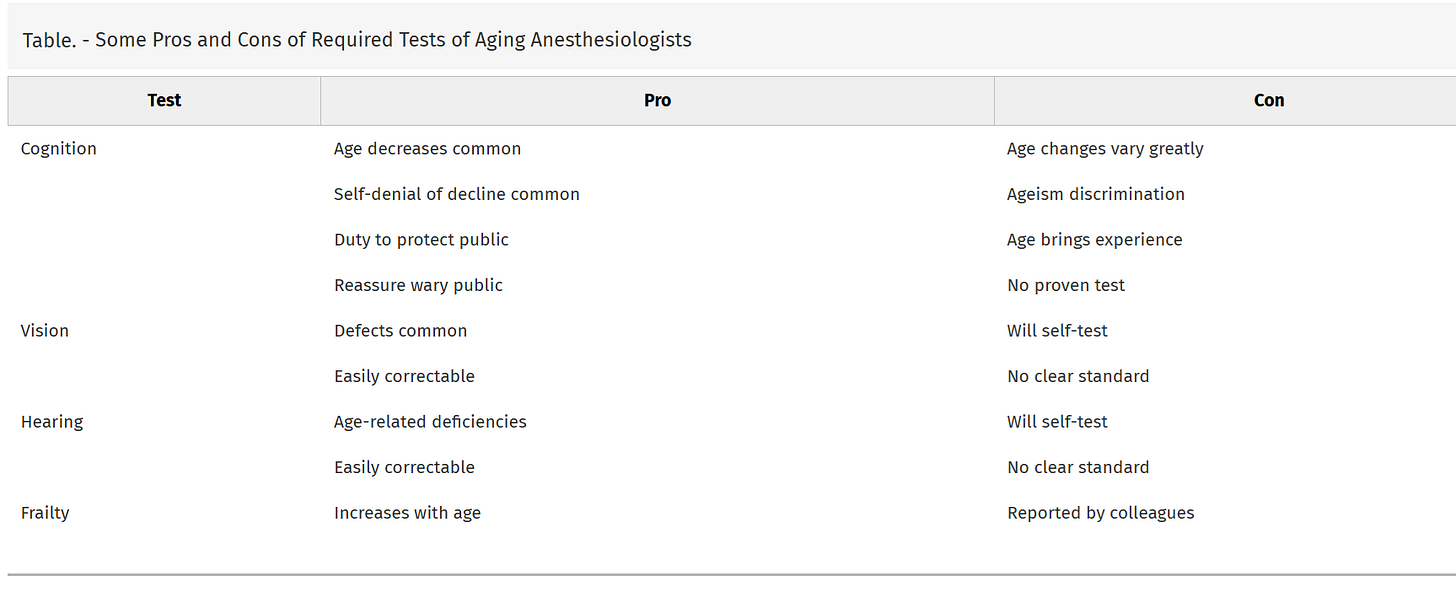

The Pros and Cons for assessing not only cognitive testing but also testing for vision, hearing, and frailty are summarized in the Table below:1

If testing physician cognition is nonetheless desired, how to do it is unclear. Cognition, the process of acquiring and using knowledge, has multiple domains, including attention, memory, and executive function, each with specific tests. Many tests of cognition exist, each better at testing some cognitive domains than others.”1 Further, whatever tests are used, they are expensive and time consuming. It is unclear who would be required to undergo testing. All ANESTHESIOLOGISTS? or specific age groups: > 50? > 60? >65? >70? Tens to hundreds of thousands of physicians and nurse anesthetists nationally would be required to undergo cognitive testing. Who will pay and who will administer the tests? And what evidence is there that it is beneficial and therefore necessary?

Finally, the American Board of Anesthesiology already mandates Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology (MOCA) for ALL of its diplomates and nurse anesthetists are required to recertify every 4 years through the National Board of Certification and Recertification (NBCRNA). The purpose is to ensure that anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists maintain and enhance their competency in the field throughout their careers. For anesthesiologists, Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology (MOCA) is an every 10-year program that is transitioning to an every 5-year program, that includes self-assessment, continuing education, and evaluation of practice. At the very least, we think hearing and vision tests for recredentialing could be mandated (as the airlines do) because degradation of hearing and vision is common, and these deficiencies may be correctable.

How to proceed? Johnstone et al. propose the following action items:

1. Base the privileges of all anesthesiologists on peer review, outcomes measurements, and comparative norms. Re-privileging should be nondiscriminatory and allow anesthesiologists to practice as long as they can safely do so. For most physicians, work performance is a sensitive measure of cognitive ability.

2. Safe anesthesia care requires adequate hearing, vision, and strength, but this does not require mandatory testing because anesthesiologists will seek testing and corrections themselves. Colleagues and other health care providers should encourage physicians to get testing if they note a deficiency. Health care providers should report physicians who perform poorly.

3. The ABA and the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research (FAER) should educate anesthesiologists on their duty to support peer review of clinical performance and patient safety and study how to do this effectively without subjective bias. FAER should support studies on the utility of OSCEs and neurocognitive tests to detect age-based declines in performance.

What do you think? Do you have age limitations in your practice? Are vision, hearing and cognitive testing used in your practice? Send your thoughts and comments to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

Reference

1. Johnstone R, Bader AM, Hepner DL: Assessing Older Anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg 2025; 140: 1105–1110

2. Katz JD: Issues of concern for the aging anesthesiologist. Anesth Analg 2001; 92: 1487–92

3. Veríssimo J, Verhaeghen P, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Ullman MT: Evidence that ageing yields improvements as well as declines across attention and executive functions. Nature Human Behaviour 2022; 6: 97–110

4. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Tsai TC, Mehtsun WT, Jha AK: Age and sex of surgeons and mortality of older surgical patients: observational study. Bmj 2018; 361: k1343