Original article

Jeffrey L Apfelbaum, Carin A Hagberg, Richard T Connis, Basem B Abdelmalak, Madhulika Agarkar, Richard P Dutton, John E Fiadjoe, et al. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 2021 Nov 11. Online ahead of print. PMID: 34762729

The new ASA difficult airway management guidelines finally include pediatric algorithms. Before we start, we need to disclose some important conflicts of interests. We were amongst the many expert consultants involved in the long process of producing these guidelines, but we were not involved in the finalized guidelines, so we hope we can give you a reasonably objective view of the finalized results. Further, we are both members of the Pediatric Difficult Intubation Collaborative and have been incredibly lucky to have forged great relationships with people interested in pediatric airway management from all over the world. So, all the pediatric experts acknowledged and unacknowledged in these guidelines are our close friends.

Let’s go straight for the highlights:

Properly position the patient, administer supplemental oxygen before initiating management of the difficult airway, and continue to deliver supplemental oxygen whenever feasible throughout the process of difficult airway management, including extubation.

There is clear data to support the use of supplemental oxygen administration to prolong the time until oxygen desaturation occurs. In our opinion, it is vital that this is a highlighted point. All too often, attempts at intubation are abandoned due to oxygen desaturation. There is strong, consistent data in adults and children that complications related to airway management are associated with repeated attempts at intubation. During airway management, the goal should be to successfully manage the airway with as few attempts as possible. Using supplemental oxygen to increase the time available during airway management is a simple intervention that is evidence based. It should always be used.

The uncooperative or pediatric patient may restrict the options for difficult airway management, particularly options that involve awake intubation. Airway management in the uncooperative or pediatric patient may require an approach (e.g., intubation attempts after induction of general anesthesia) that might not be regarded as a primary approach in a cooperative patient.

This is explicit recognition that most children cannot be intubated awake. It may seem obvious to all of you, but having it explicitly expressed in a national guideline helps from a practical and medicolegal standpoint.

But, what about the lowlights? Well, for us there are a few significant problems with these guidelines. This is purely our personal points of view (and we are sure there will be many people reading this who do not agree with us and if you do, send us your thoughts…Myron will get them posted in the PAAD), but we think this was a missed opportunity to emphasize that traditional direct laryngoscopy (DL) is a poor technique to use in children who are difficult to intubate. The evidence we do have is not perfect, but it is very clear that DL should not be used in these children. In fact, we know that videolaryngoscopy (VL) is superior to DL in small infants with normal airways, let alone difficult airways! What we don’t know, is which advanced technique (standard blade VL, hyperangulated VL, flexible bronchoscopy, combination techniques – VL plus FBI, FBI through a supraglottic airway, etc…) should be used in any given situation. There should be a clear statement that the first attempt at intubation should be made using an advanced airway technique, NOT DL. If DL is used, it should be performed using a VL system that enables DL, video-assisted DL and indirect VL to be performed during the same laryngoscopy attempt (e.g. with the Storz C-Mac, or Verathon Glidescope Miller/Mac blades).

We were curious as to why this was not explicitly stated in the guidelines, and the references quoted do not appear to include the pertinent papers – these are from the PeDIR, and several of the experts named in the pediatric guideline footnotes were authors on these papers, so why were they ignored? There is also no mention of the excellent European studies that were recently published (Nectarine and Apricot) – again, the authors of these papers were heavily involved in these guidelines and named in the footnotes, but these papers are not referenced.

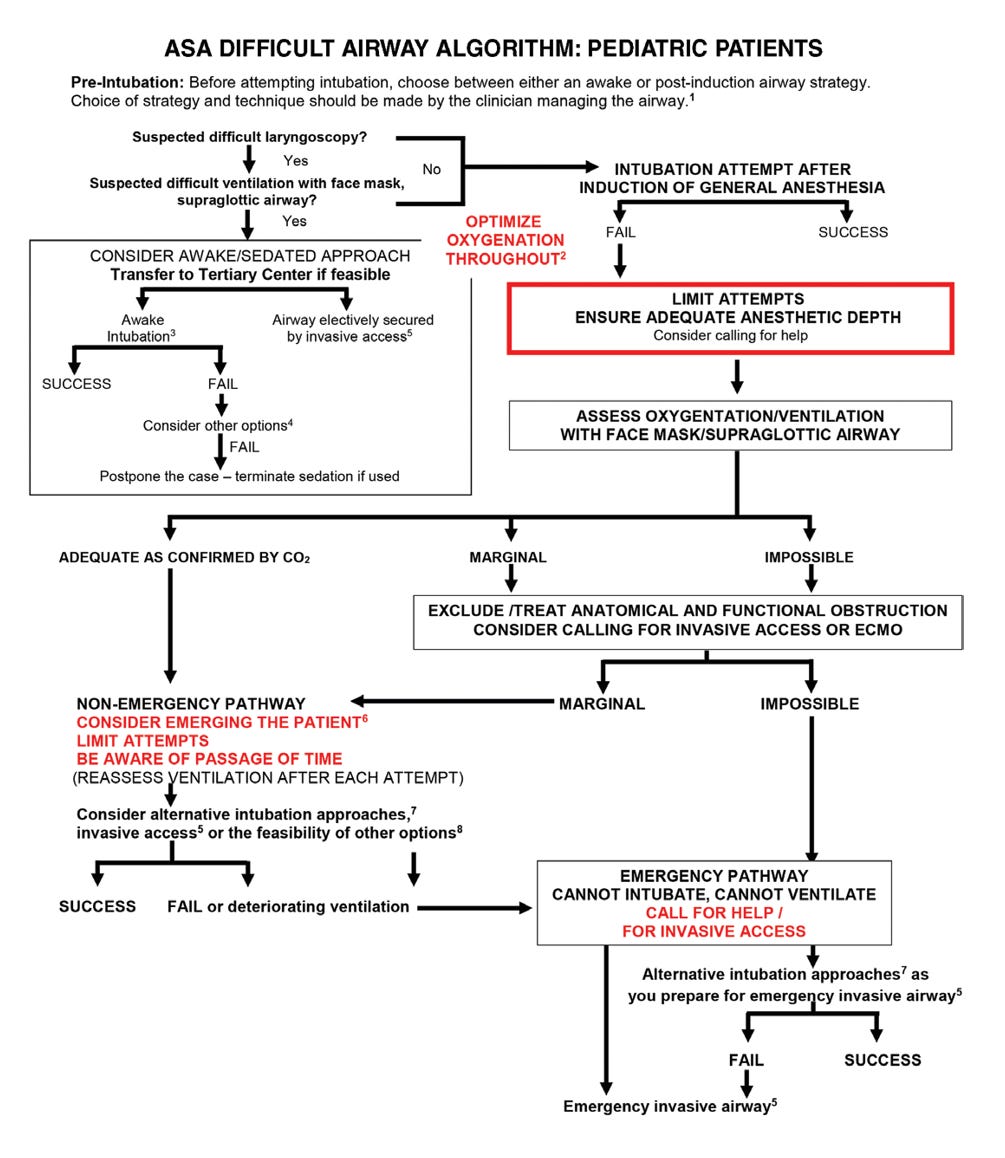

Secondly, we were disappointed in the flow charts and diagrams produced. It is incredibly difficult to produce simple diagrams that effectively summarize complex systems. We think the ASA failed to produce a useful set of resources that can be referred to in a practical setting. The paper itself is incredibly difficult to read. Indeed, we understand why (because it is seeking to distill all the current evidence available in difficult airway management and document exactly how these guidelines came about). We get it, but consequently they’ve produced a document that is comprehensive, but practically unreadable and unusable. We would like to see a set of practical, clinically usable guidelines, including crisis management resources that could be used in any OR created as part of this work. We have attached the key diagrams from this paper and our preferred cognitive aid, the Vortex approach from Australia (please consider how difficult it is for me (JP) a British person to give credit to anything from Australia, so it must be good!). It would be interesting to get a human factors expert like Barbara Burian who helped create the PediCrisis App and graphic designer to create better diagrams from these guidelines. The other alternative is to just admit that it’s been done better elsewhere and use existing diagrams.

In short, the recommendations should simply say a few things:

- Ask for help before you start

- Use supplemental oxygen

- Use advanced airway techniques for your first attempt (NOT DL)

- Do not persist with failing techniques

- Do not persist with failing providers

- Do not delay eFONA or ECMO if you cannot oxygenate

And that’s it. In terms of pediatric difficult airway management, we think that printing those 6 lines out and sticking them up in an OR and/or building them into the next version of SPA’s PediCrisis app and SPA printed checklist cards may be more practically useful than the ASA practice guidelines. We hope part the next guidelines will focus more on creating clinically useful tools, that can be developed from all the excellent work they have done to produce these thorough, yet not particularly up to date or useful, guidelines*.

Let’s write the PeDi Guidelines 😃

información valiosa. Gracias