Addressing Late-arriving Surgeons in Support of First-Case On-Time Starts

Kim Strupp MD and Lynn Martin MD MBA

As promised, the PAAD is continuing to increase our reviews of quality and safety and process improvement manuscripts. In today’s PAAD, from the journal Pediatric Quality and Safety, Ida et al. focused on first-case on-time starts (FCOTS) and how late-arriving surgeons affect perioperative efficiency.1 FCOTS is a widely used metric in perioperative management, aligning with efficiency, one of the six domains of healthcare quality.2,3 Ensuring ORs start on time not only improves timeliness throughout the remainder of the day, it also enhances patient and staff satisfaction4 while reducing costs by decreasing overtime pay. Indeed, “it is clear that surgeon conduct, professionalism, and accountability have explicit and implicit effects on perioperative performance.”1 Myron Yaster MD

Original article

Ida JB, Schechter JH, Olmstead J, Menon A, Lafelice MB, Sawardekar A, Leavitt O, Lavin JM. Addressing Late-Arriving Surgeons in Support of First-Case On-Time Starts. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2025 Jan 7;10(1):e784. doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000784. PMID: 39776946; PMCID: PMC11703430.

Despite late-arriving surgeons (LAS) being one of the commonly cited reasons for delay, many institutions hesitate to tackle this seemingly immovable obstacle, instead opting to focus on other, seemingly more manageable, factors. However, Lurie Children’s hospital, a 360-bed free-standing tertiary pediatric hospital with 21 primary operating rooms, took a different approach—addressing the issue head-on. Their efforts, detailed in this article, led to notable success in reducing LAS and improving FCOTS.

The Strategy: Clear Expectations and Accountability

Lurie’s goal was ambitious: reduce LAS frequency by 30% (from 24 to 16 per month) over four months and sustain that improvement for two years. Their expectation was simple— surgeons were merely to arrive at least 15 minutes before the scheduled surgical start time (0715 for a 0730 start), with a 5-minute buffer to be considered “on-time” in the OR (0735 for a 0730 start). Surgeons were expected to maintain a late arrival rate <20%.

To enforce accountability:

· Late arrivals triggered an email notification within 24–48 hours, requiring an explanation.

· Surgeons exceeding the 20% threshold over three months faced potential consequences from the perioperative surgical leadership.

· The most significant penalty? Loss of first-case start privileges for three months, requiring them to follow other surgeons in the schedule.

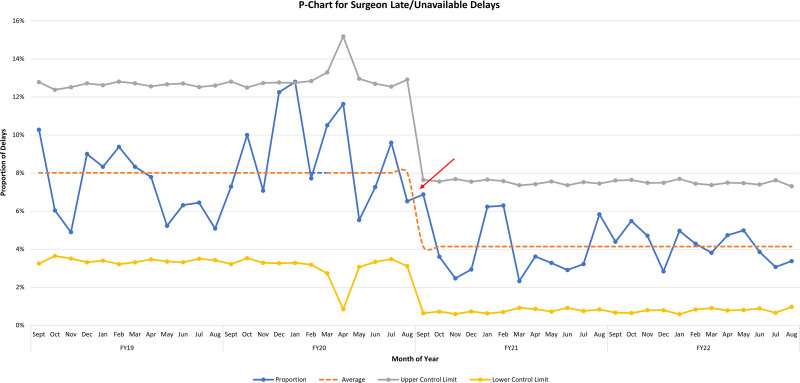

Wow! That’s an aggressive penalty for the surgeons showing up late. It’s no surprise that this high-stakes consequence led to swift behavioral changes. The surgeons immediately started showing up on time so as to not lose their precious block time! They saw a 45% decrease (p<0.001) in surgeons arriving late over the 2-year study period, with a shift from 8% to 4% LAS on their statistical process control chart (see figure). First case on-time starts increased from 66% to 72% (p<0.001) (see figure). No surgeons required an adjustment to their block time – the threat worked to change their behavior. Three surgeons required some discussion from leadership and a probationary period – all changed their behavior with these interventions.

Why does this matter? Besides efficiency gains, patient and staff satisfaction, and cost savings, getting surgeons (and anesthesiologists) to show up on time significantly impacts the perioperative team moral and professionalism. The authors highlight that addressing LAS was a critical step in fostering a culture of respect and reliability among the entire team.4 When we (KS) started our FCOTS work at Children’s Hospital Colorado in November 2023, I resisted the idea of simply asking our team to “do better” or “work harder” without looking at opportunities for systems-based improvements. What I’ve personally learned in our FCOTS journey is that setting clear expectations and holding people accountable are key factors that should be leveraged alongside systems-based improvements. While there have been no threats of adjusting block time in our institution, providing data transparency to our surgeons has resulted in some remarkable improvements, especially amongst some of the lowest performers. We had one surgeon go from 30% FCOTS one month to 100% FCOTS the following month after seeing his own data vs his peers!

Now let me (LDM) to be more provocative and add some fuel to this fire to stimulate more dialog. It is very nice to see that this single intervention caused an improvement and that it has been sustained. However, there are additional reasons cases do not start on time. Why are you satisfied with only 72%? Why can’t you get to 90%? My last shot across the bow, ok you got your first case started on time. What about the next case, next case, and so on? Doesn’t every patient deserve to have their case start on time? That is why we (Seattle) stopped focusing on simply FCOTS and pivoted to All Case On-Time Start (ACOTS). In our ASC we have an 86.4% ACOTS rate for the current fiscal year. FCOTS is a great place to start and learn how to improve together as a team, but please do not stop there!

What do you think? Is FCOTS an important metric at your institution? What strategies have you used to address late-arriving surgeons and anesthesiologists? Please send your thoughts to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

1. Ida JB, Schechter JH, Olmstead J, et al. Addressing Late-arriving Surgeons in Support of First-case On-time Starts. Pediatr Qual Saf 2025;10(1):e784. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000784.

2. Pashankar DS, Zhao AM, Bathrick R, et al. A Quality Improvement Project to Improve First Case On-time Starts in the Pediatric Operating Room. Pediatr Qual Saf 2020;5(4):e305. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000305.

3. Phieffer L, Hefner JL, Rahmanian A, et al. Improving Operating Room Efficiency: First Case On-Time Start Project. J Healthc Qual 2017;39(5):e70-e78. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/jhq.0000000000000018.

4. Piper LE. Addressing the phenomenon of disruptive physician behavior. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2003;22(4):335-9. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/00126450-200310000-00007.

Thanks so much for posting our article here, it was a surprise and delight to see it publicized like this. One of the most important lessons we learned from this was how dependent the integrity of the data was on the improvement process. As noted in the paper, in prior state, our process had no input from the surgeons, and so "surgeon late" became over-inflated. This didn't let surgeons off the hook (was still the largest #), but rather showed us what issues we had that were UNDER-estimated and allowed us to address those, also, and work toward holding everyone accountable. Thanks again!!! -Jonathan Ida