A spoonful of honey does NOT reduce the pain of tonsillectomy

Myron Yaster MD, Melissa Brooks Peterson, and Francis Veyckemans MD

We recently published a PAAD (01/03/2025) by Yeoh et al.1 of a metanalysis that suggested that honey could promote quicker healing and reduce pain following tonsillectomy when electrocautery was used (https://ronlitman.substack.com/p/copy-a-spoonful-of-honey-may-help ). Indeed, it was one of the most read PAADs of January. In that paper, the authors concluded “that honey may be beneficial BUT also warned that much more formal research was needed to investigate the effects of honey in post tonsillectomy pain.” Why more studies? Yeoh et al. was a metanalysis of previously published studies but these studies “were of poor quality and were not double blinded, randomized nor controlled.”1 In today’s PAAD, the same group led by Dr. Britta S. von Ungern-Sternberg (first author: Dr. David Sommerfield2) performed a follow up, multi-center, prospective, randomized trial in children undergoing extracapsular tonsillectomy by coblation to confirm the findings of the Yeoh study. Perhaps not surprisingly, today’s PAAD, which is a larger multi-institutional, prospective, randomized controlled trial found different results than the metanalysis, highlighting the importance of actually performing randomized controlled trials to form the basis of our conclusions.

On a personal note, pain following T & A surgery has always been an interest of mine. Many years ago, one of my colleagues at Hopkins called me in distress. His 4-year old granddaughter had undergone a T&A and in the 1st 24-48 hours following surgery, the child was in substantial pain, could not drink nor swallow, and was inconsolable. She “fired” her grandfather! I asked about her pain regimen, and despite being prescribed oxycodone liquid, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen by the surgeon, the parents would not give the kid oxycodone because of information they obtained by Dr. Internet. I knew the family well, indeed, my own kids were baby sat by the child’s mother when my kids were young and the parents knew that I was a pediatric anesthesiologist like the grandfather AND a pediatric pain specialist. I urged them to give the oxycodone a chance. They did and the miracle of opioids became self-evident almost within minutes. As I explained to the parents and as I’ve written in many previous PAADs: “The reason opioids have been used therapeutically for thousands of years is because they work!” Myron Yaster MD

Original article

Sommerfield D, Sommerfield A, Evans D, Hauser N, Vijayasekaran S, Bumbak P, Herbert H, Locher C, Lim LY, Khan RN, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Impact of honey on post-tonsillectomy pain in children (BEE PAIN FREE Trial): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. 2025 May 5. doi: 10.1111/anae.16619. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40321015.

Tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy remains one of the most frequent and painful surgical procedures performed in children. “Recovery is often difficult with pain (particularly on swallowing), poor oral intake and risk of haemorrhage and infection.3 Indeed, for many children, pain after tonsillectomy represents the worst part of the experience4 and studies report medical representations because of pain and hemorrhage as high as 50–70%.5,6

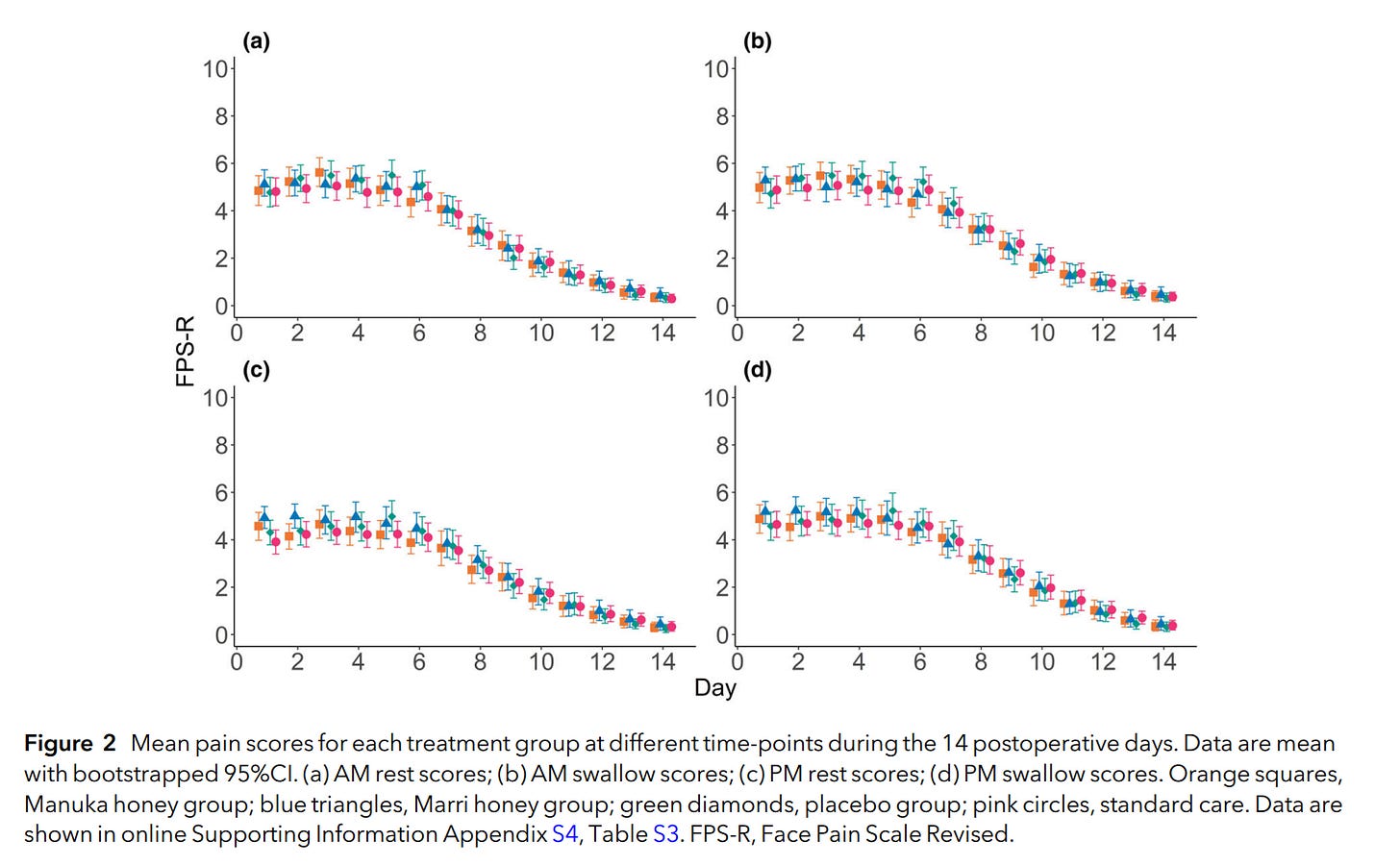

Study design: Children (aged 1–16 y) undergoing elective extracapsular tonsillectomy with local anesthetic infiltration by the surgeon (+/- adenoidectomy; cautery of inferior turbinates; myringotomy; examination of the ear; insertion of grommets) were eligible for inclusion. Patients “were allocated randomly to one of four postoperative treatment groups: standard treatment alone; Marri honey (Corymbia callophylla from Western Australia); Manuka honey (Leptospermum scoparium from Western Australia); or placebo ‘honey´ (composed of glucose syrup, rice malt syrup and PharmAustTM syrup BP (PharmAust Manufacturing, Malaga, WA, Australia) with no additives). The intervention groups were invited to take 5 mL of honey or placebo, six times a day, for at least 7 days, in addition to usual discharge analgesia (standard treatment). The most commonly used intra-operative opioids were fentanyl 1–2 mcg/kg and/or morphine 0.05–0.1 mg/kg. All children stayed at least one night in hospital. The treating team had the final discretion on discharge medications with the prescribed regimen: oral paracetamol 15 mg/kg four times daily for 7 days, then as required; oral ibuprofen 10 mg/kg three times daily for 7 days, then as required; and oral oxycodone between 0.05 and 0.1 mg/kg 6-hourly as required. Data for daily pain scores, Parents’ Postoperative Pain Measure scores, medications and unplanned re-presentations were collected.”2 Follow up at home was remarkable. Participating parents/guardians were asked to document pain scores using a paper diary for 14 days postoperatively. Self-reported pain scores were determined four times daily using the Face Pain Scale Revised, twice to assess the background or `at rest´ pain intensity and twice with swallowing. Pain scores were collected in the morning around breakfast (AM rest and AM swallow), then repeated around the evening meal (PM rest and PM swallow). Parental proxies were used for children aged < 6 y. Parents were also asked to complete a slightly modified Parents’ Postoperative Pain Measure. Moreover, parents were sent a REDCap link each evening to transfer data from their diary. If 2 days in succession were missed, research staff would collect responses by phone.

OK, what did they find? “A total of 400 children were recruited; 20% were lost to follow-up or withdrew. The mean number of honey doses taken varied between 2 and 3 doses per day over 7 days. Treatment with honey at this frequency did not impact postoperative pain scores significantly, with all groups showing similar trajectories. These findings did not alter with as-treated analysis or using imputed models for missing data. Most children experienced significant pain until around postoperative day 8. Children allocated to the honey and placebo groups showed some improved oral tolerance around day 6 but had increased vomiting during earlier days. There were no clinically significant differences in medical re-presentations, simple analgesia or oxycodone usage between groups.”2

Simply, honey did not work at preventing pain, the recovery trajectory or need for supplemental analgesics in children who underwent tonsillectomy. It did increase the incidence of nausea and vomiting. Further, despite the strict follow up, compliance with the around the clock honey administration was poor. Indeed, most patients received only 2 doses of honey and not the 6 doses they were supposed to receive. Perhaps 2 doses of honey may be insufficient to produce sufficient biological effect during the critical peak inflammatory days, when swallowing is most painful. Moreover, compliance with the prescribed analgesic treatment prescribed was also unsatisfactory:” Across groups, just under half of the children documented taking the recommended analgesic doses on a given day. The number of doses of paracetamol and ibuprofen used were within half a dose across groups, across all days”

Finally, the authors note that “post-tonsillectomy pain is worst in the mornings, worse with swallowing and lasts about 10–14 days, and honey could have potentially altered any of these. Of the eight previous studies with children using honey and examining pain, only two used both resting and swallowing discomfort; four monitored for 5 days or less; only one had 14 days of data; and two used scores only every 3–4 days. For example, reviewing pain in our cohort at day 7, without considering the days immediately before and after, one might erroneously conclude that honeys were significantly better according to parents.”2 We think that this laudable study by Sommerfield et al. demonstrates the power of a carefully designed randomized prospective trial and why studies using meta analysis can provide erroneous conclusions. Moreover, it also shows the difficulty of conducting prospective research in pediatric patients at home and the need for better education of parents regarding their child’s pain and pain management.

What do you think? Send your thoughts to Myron who will post in a Friday reader response.

References

1. Yeoh MF, Sommerfield A, Sommerfield D, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. The use of honey in the perioperative care of tonsillectomy patients—A narrative review. Pediatric Anesthesia 2024;34(10):988–998. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14938.

2. Sommerfield D, Sommerfield A, Evans D, et al. Impact of honey on post-tonsillectomy pain in children (BEE PAIN FREE Trial): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia 2025 (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/anae.16619.

3. Lagrange C, Jepp C, Slevin L, et al. Impact of a revised postoperative care plan on pain and recovery trajectory following pediatric tonsillectomy. Paediatric anaesthesia 2021;31(7):778–786. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/pan.14187.

4. Bell E, Dodd M, Sommerfield D, Sommerfield A, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Kids voices: Exploring children's perspective of tonsillectomy surgery. Paediatric anaesthesia 2021;31(12):1368–1370. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/pan.14288.

5. Stewart DW, Ragg PG, Sheppard S, Chalkiadis GA. The severity and duration of postoperative pain and analgesia requirements in children after tonsillectomy, orchidopexy, or inguinal hernia repair. Paediatric anaesthesia 2012;22(2):136–43. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03713.x.

6. Williams G, Bell G, Buys J, et al. The prevalence of pain at home and its consequences in children following two types of short stay surgery: a multicenter observational cohort study. Paediatric anaesthesia 2015;25(12):1254–63. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/pan.12749